This piece is the newest version of my yearly attempt to describe the style of every USL Championship team. Club by club, I’ll map out a typical formation with mark-ups to denote tactical trends.

I published a similar guide to the last season, and you can find it at the link here if you’re interested in 2022’s New York Red Bulls II.

As with everything published under the USL Tactics banner, this guide isn’t unassailable. Tactics are subjective and fluid. What one person calls a “4-2-3-1” might be a “4-4-2” to someone else or a “back three” without the ball. Lineup graphics are also suggestions rather than be-all, end-all declaration. Injuries and rotations are constant, and I’m suggesting best-case teams here.

With all that said, let’s get to it.

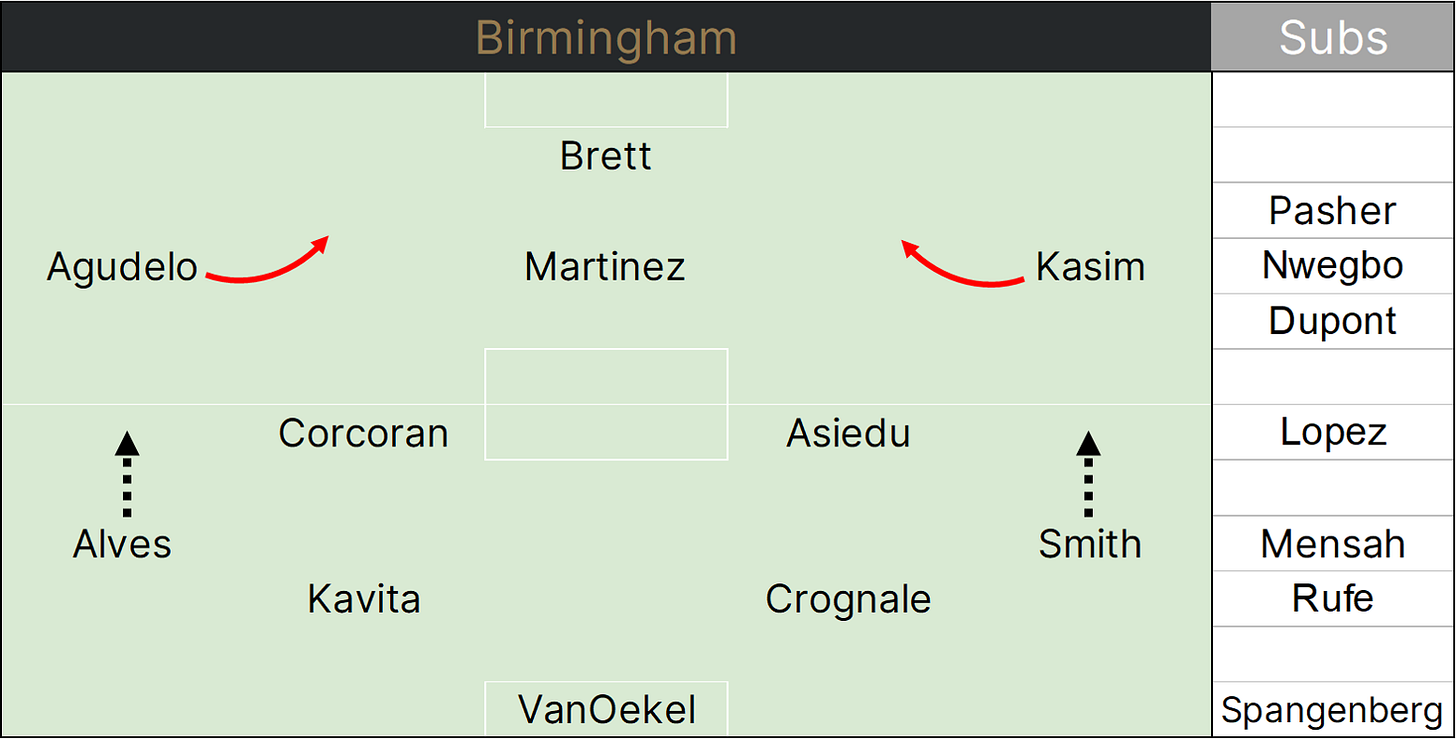

Birmingham Legion

The Legion use a four-at-the-back shape that often presses into a 4-2-4. Enzo Martinez, used as the second striker or No. 10 in the baseline 4-2-3-1, will join a proper No. 9 striker and two elevated wingers to close down on opposing build.

One line behind, the Birmingham full backs are expected to actively cover behind the press. This can effectively limit breaks, but it also opens holes in the channels. In those situations, the Legion rely on their pivot - most often Anderson Asiedu and a partner - to drop into FB position in rotation.

With the ball, Birmingham is moderately possessive and rates mid-table in terms of long passing and long restarts. Their build drives through Alex Crognale, a good passer at center back, and one or two CMs dropping deep as passing outlets. Matthew Corcoran has also emerged as a solid passer in the pivot.

Up the pitch, the Legion often employ inverted wingers and encourage those wide men to tuck inside to create overloads. Juan Agudelo, a natural No. 9, can also take on a narrow wing role where he’s regularly charged with hold-up play. Meanwhile, Martinez is liberated to roam and receive the ball in either half space to drag the defense out.

This narrowing on the flanks opens up overlaps from the FBs. Birmingham encourages their wide defenders to advance freely to support the offense.

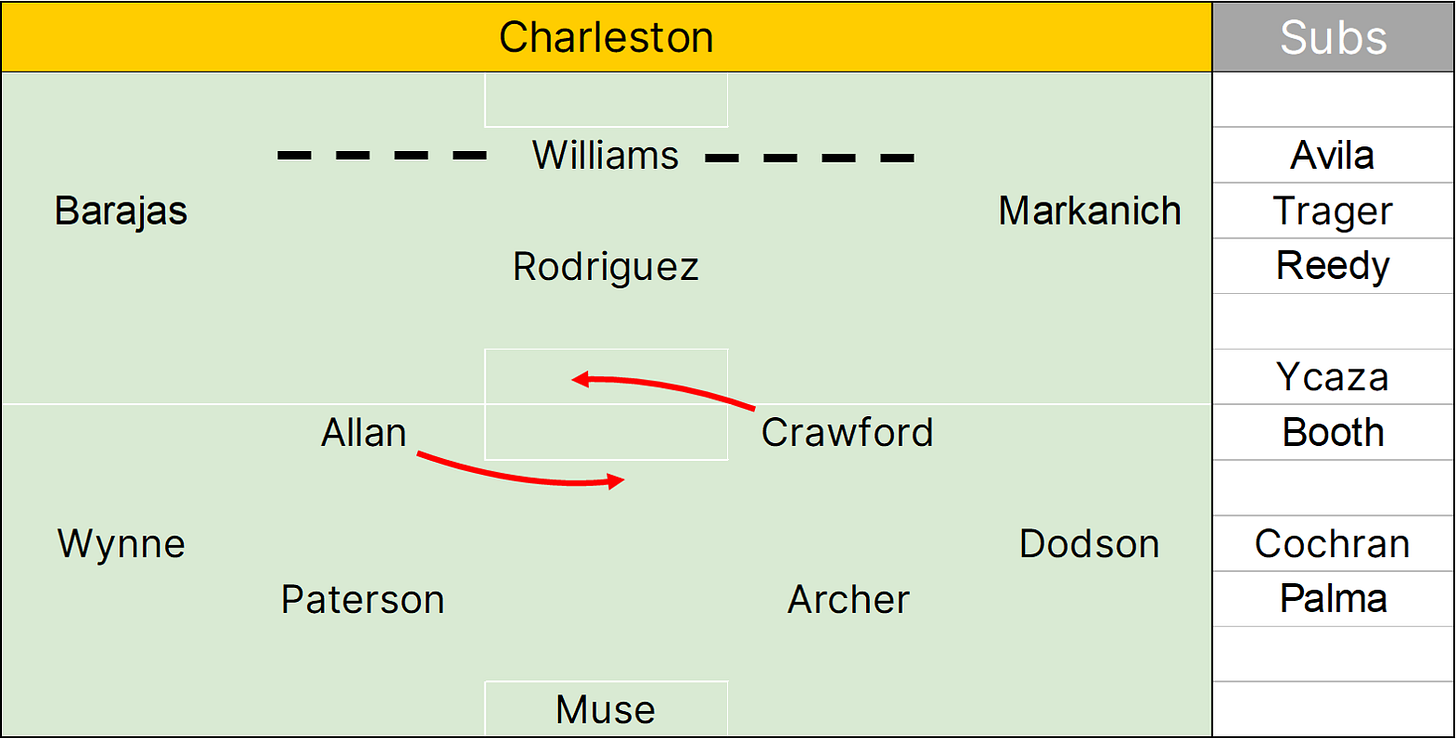

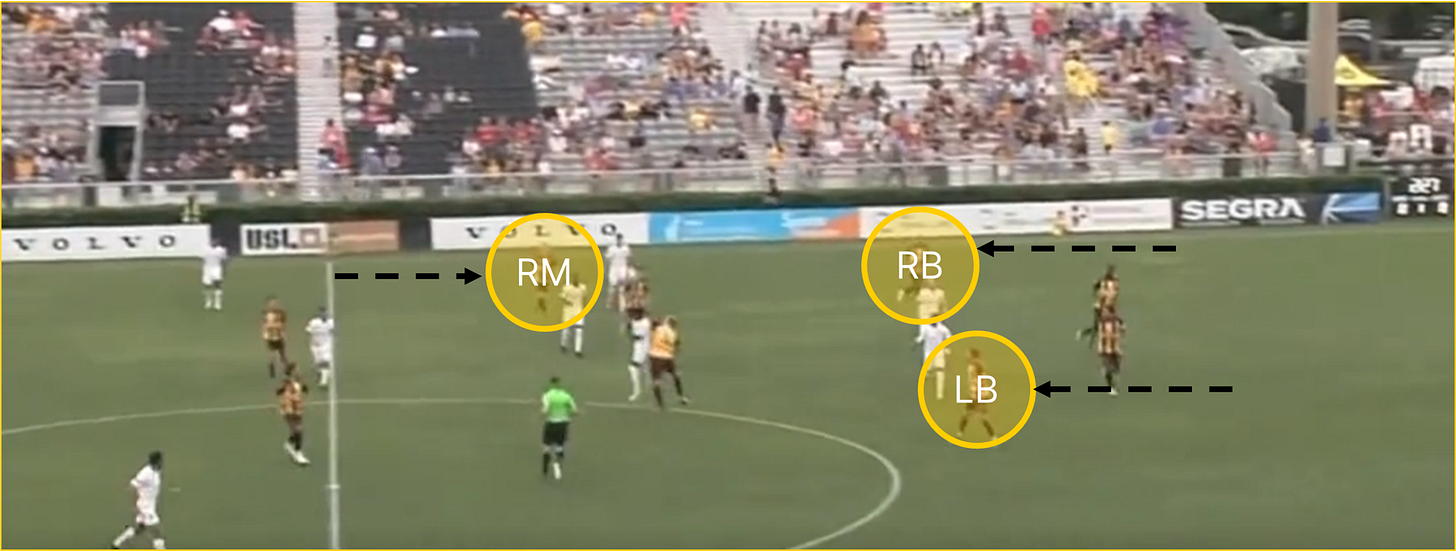

Charleston Battery

Charleston’s 4-2-3-1 can often turn into a 4-3-3 in the press with the No. 10 roving a line behind. In the pivot, the dual centermen take turns sitting back as a proper No. 6 defensive midfielder or adopting on a freer, more expansive role. Matchups dictate who joins the crucial Chris Allan there.

The Battery play a high line on restarts, and they rely on their center backs - especially AJ Paterson or Juan Sebastian Palma - to use their pace to cover behind advanced full backs. Those FBs press high quite often, and they’re aggressive when Charleston has possession.

In terms of deployment, Ben Pirmann sometimes turns to Robbie Crawford, a natural central midfielder, as a winger. This can happen when injuries arise or when the Battery are facing an especially potent attacker on the flanks, but Crawford provides offensive upside on long restarts as well.

Indeed, the Battery increasingly have gone direct in build-up as the season has worn on. Augustine Williams is the main target, and he’s given leeway to stretch from side to side as an outlet for Trey Muse from the back. Williams, the star striker in the squad, is also adept at stretching defenses on the break or poaching and holding the ball up in settled phases of play.

When Beto Avila joined the team, he became a second long outlet on the wing alongside Williams.

Ideally, Pirmann prefers controlled sequences that drive through the pivot into slick-dribbling, creative players in the vein of Fidel Barajas or Tristan Trager. Notable offensive spells see them or do-it-all midfielder Nick Markanich rotate up top, dragging defenses out.

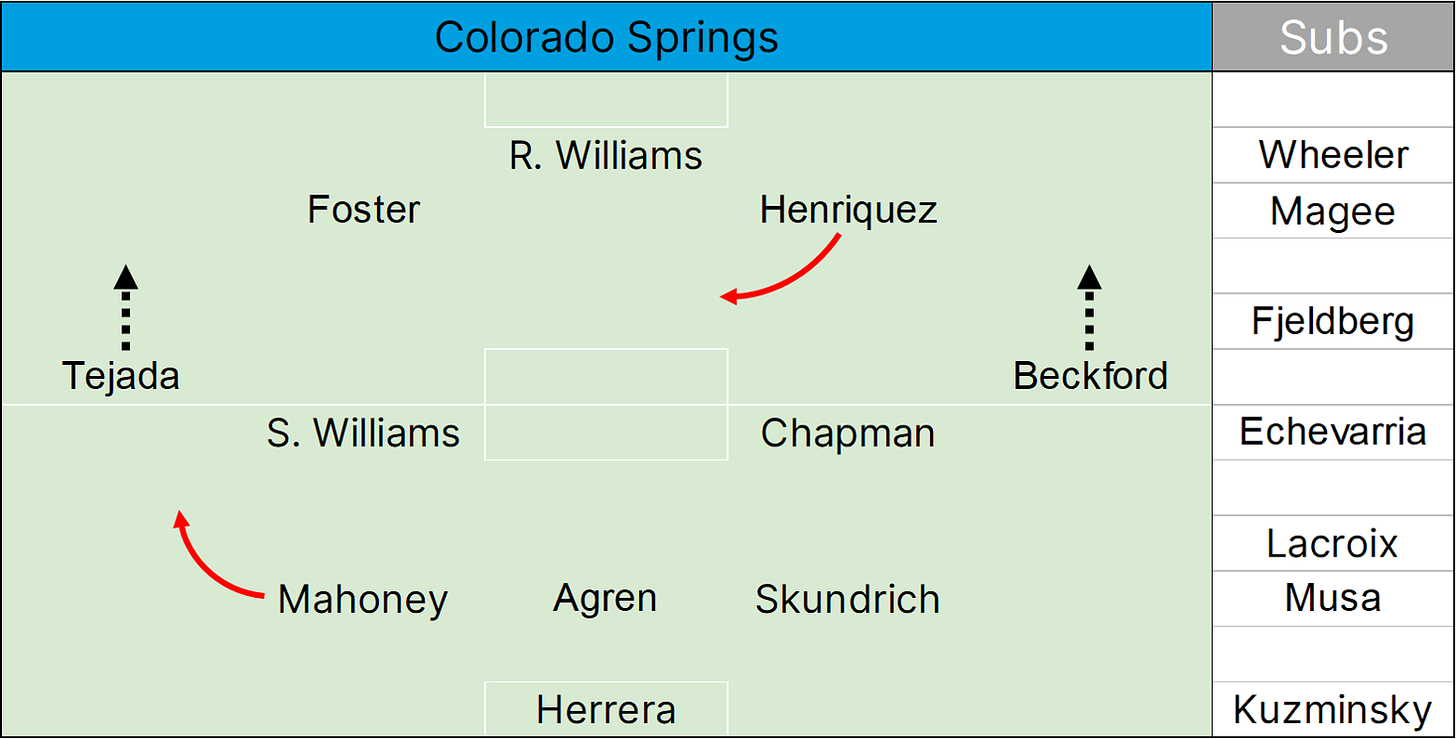

Colorado Springs Switchbacks

Beginning the season predominantly in a 3-5-2, swapping into a proper 4-4-2, and belatedly landing on a freer 3-4-3, Colorado Springs has been a tactical chameleon in 2023. They are generally passing passive without the ball, holding a flat midfield line while allowing the forwards to rove and close off passing angles.

The back three can be somewhat aggressive in terms of ball carriage - especially through Matt Mahoney or Duke Lacroix - but generally settles in as a middle-high line across the match. In block, the wing backs drop into a fivesome, and the CM group is expected to cover from side to side in front of them.

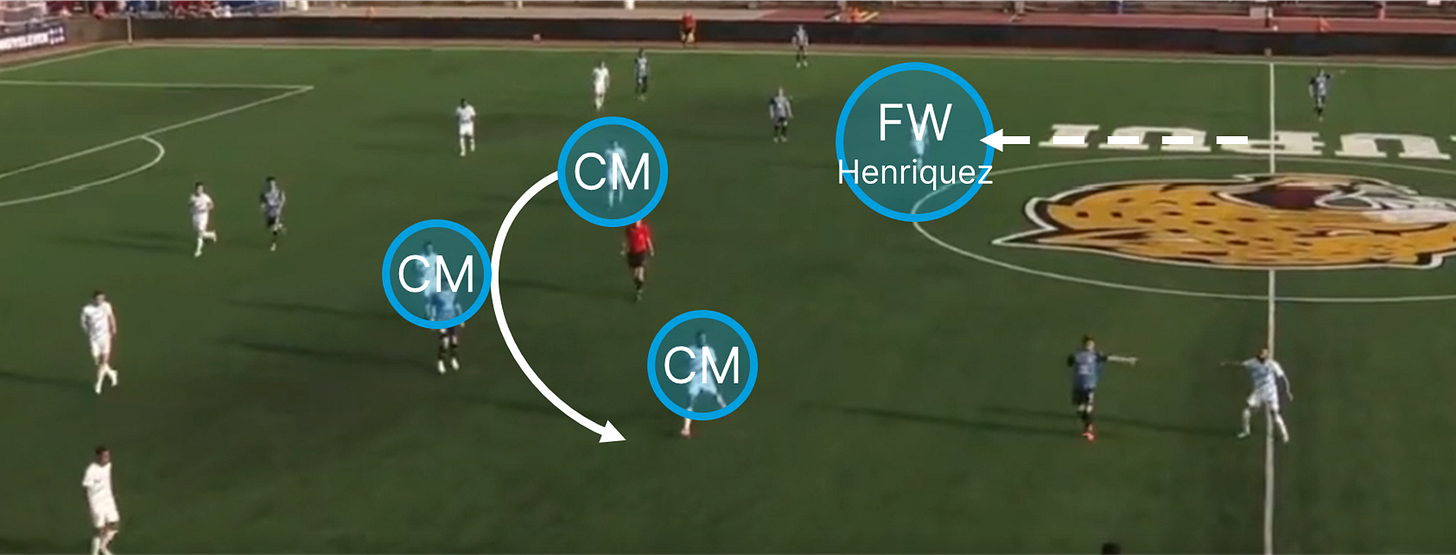

Still, there’s fluidity innate to the look. Deshane Beckford and his wing back peers are allowed to fly up the sidelines to create a 3-2-5 in possession. Maalique Foster has a tendency to drift wide up top, and fellow attacker Jairo Henriquez drifts all over the pitch to create.

Henriquez is the turnkey within this Switchbacks side. He often starts at the tip of the midfield three or as a second striker, but #17 is allowed to drop in next to the center backs if he so chooses to facilitate build-out. Midfield rotation driven by Henriquez is key to drawing opponents narrow and opening up the flanks.

Tyreek Magee provides a similar skillset to Henriquez off the bench and is used when the side wants to dominate the final third; Aaron Wheeler is a prototypical lump-it-long emergency sub.

Stephen Hogan also breaks out a 4-3-3 at times, a shape that is less susceptible to counterattacks down the channels. Using two conservative full backs, the formation relies on the speed of wingers like Beckford and Foster to stretch opponents and open windows into Romario Williams as the No. 9.

Detroit City FC

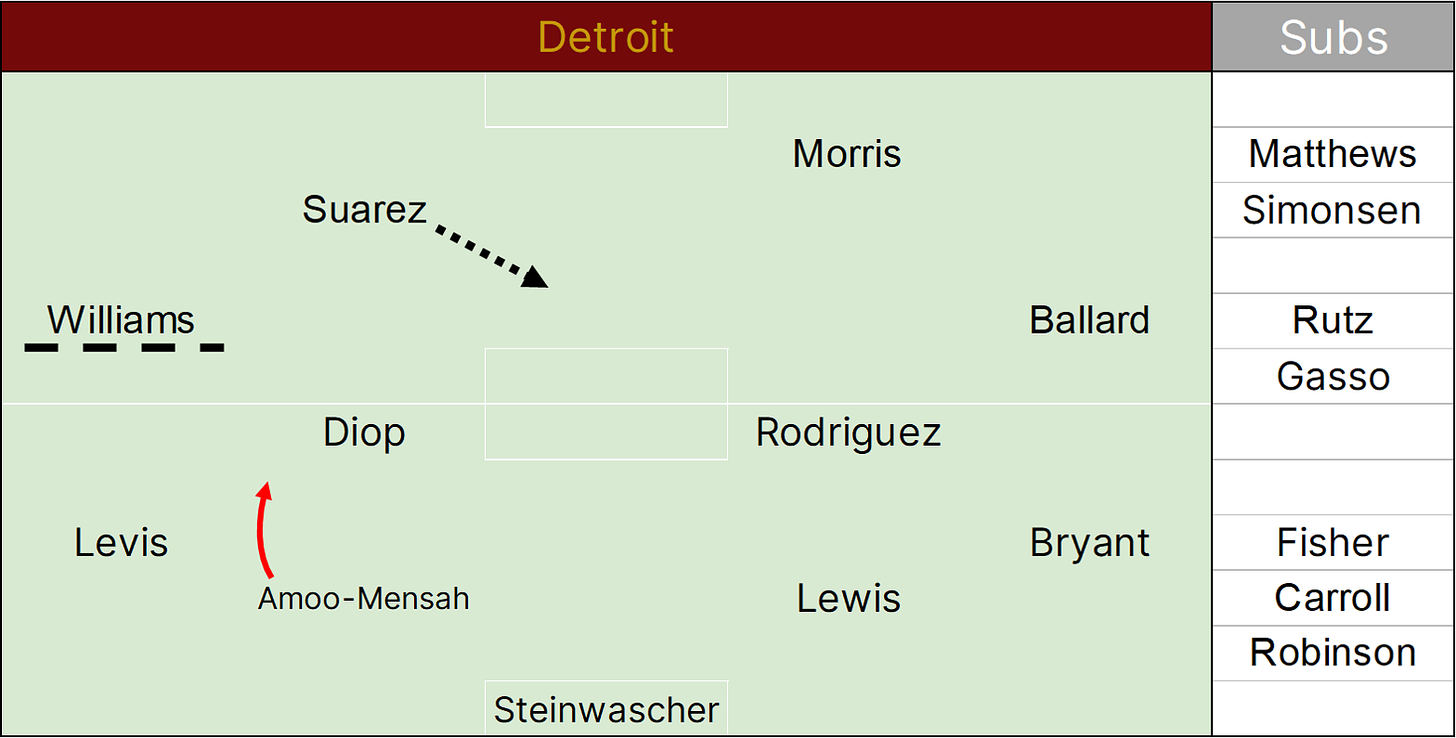

One of the best-organized defensive sides in the USL, Detroit has swapped between a 3-4-1-2 and 4-4-2 depending on health. A back three is their preferred shape in a vacuum, and it relies on a deep, low line as a catch-all safety net in front of Nate Steinwascher.

Though they have used a dual-No. 6 pivot at times, Le Rouge prefers to pair one defense central midfielder next to the free-flowing Maxi Rodriguez. The latter often drifts toward the sideline to fill for a high-flying wing backs, allowing him to create from the half spaces.

Often employing the 4-4-2 later on in the season, Detroit varies the height of their forwards by using Dario Suarez as a roving presser behind true striker Ben Morris. In this shape, Suarez and the wingers can occasionally press up into a 4-2-4.

Offensively, the team is very direct and settles for long balls from the back into their pair of physical forwards. Goal kicks and other deep restarts are equally lengthy. One oft-used alignment sees Rhys Williams advance as a “third forward” in the wide areas of the 3-5-2 or 4-4-2 to serve as a target for these passes.

While opportunities can ensue from this style, especially when the WBs glom onto second balls, the tactics often means that Detroit lacks for flow and cannot engage their No. 10 in advantageous positions while rushing to lump the ball downfield.

El Paso Locomotive

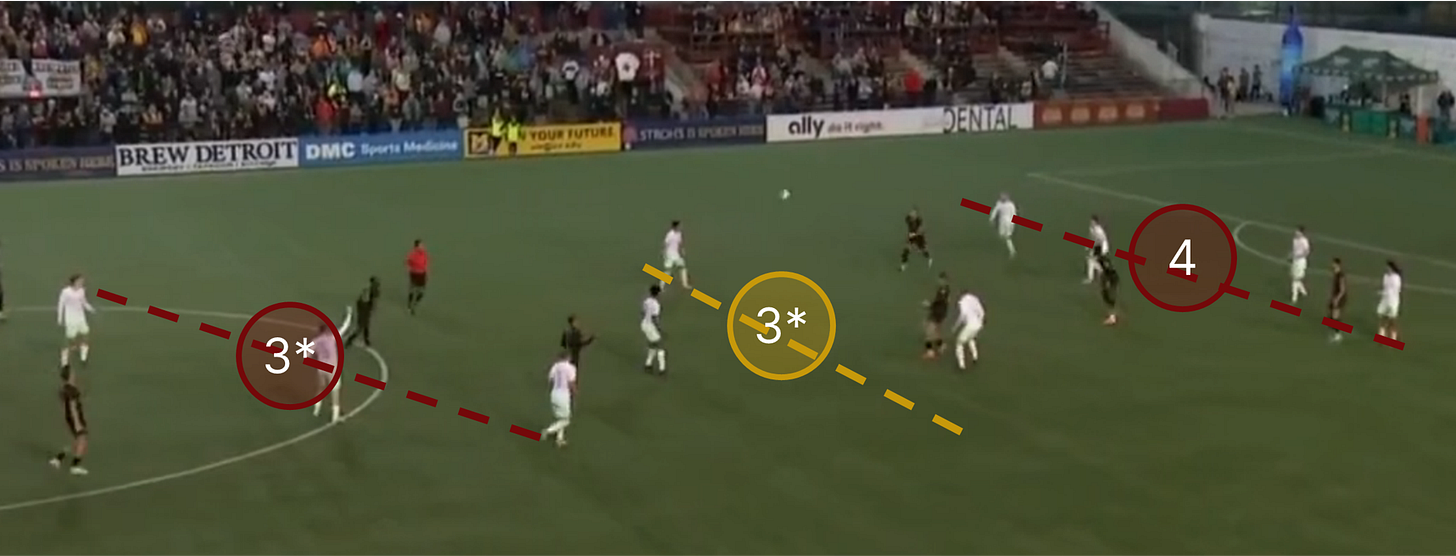

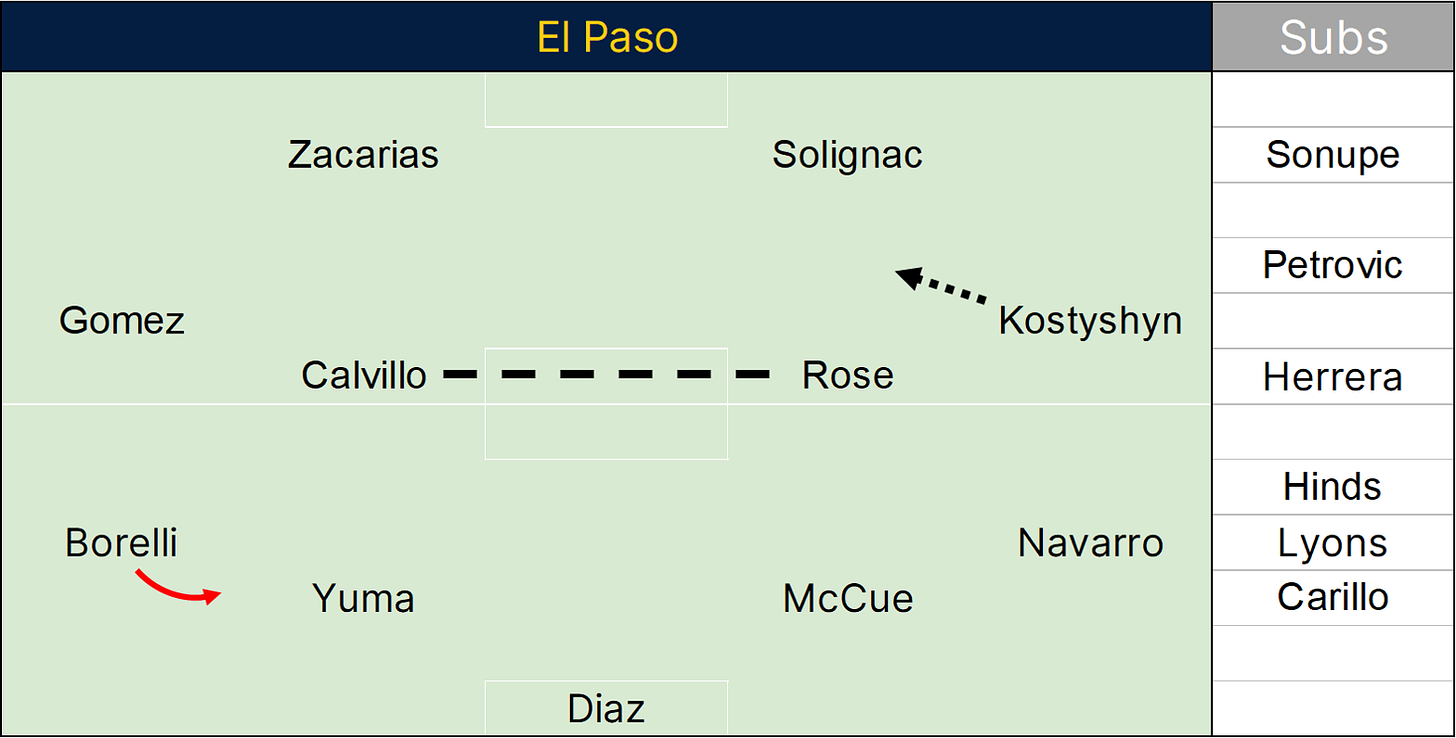

Basing their shape out of a 4-4-2, El Paso shows great discretion in pinching towards certain areas of the pitch while retaining an underlying organization. They dominate possession thanks to a measured press that strikes a balance between aggressive closing and lane denial.

Despite employing somewhat slower center backs, the Locomotive’s back line takes on a high-ish position to compress space behind the midfield. This tactic succeeds thanks to the responsibility shown by Eric Calvillo and Liam Rose in the midfield pivot.

El Paso plays very short with the ball, using Benny Diaz as an active passing outlet from the goalkeeper spot. Often, left back Eder Borelli or right winger Denys Kostyshyn will drop even with the pivot to create overloads behind the first line of pressure that can open passing lanes for Diaz or the CBs.

Up the pitch, the Locomotive actively rove and interchange in the forward line. The left winger, usually Petar Petrovic or Emmanuel Sonupe, will advance and swap with strikers like Ricardo Zacarias. Luis Solignac’s do-it-all ability to engage in these patterns while providing elite hold-up and poaching as a No. 9 in a pair greases the wheels on offense.

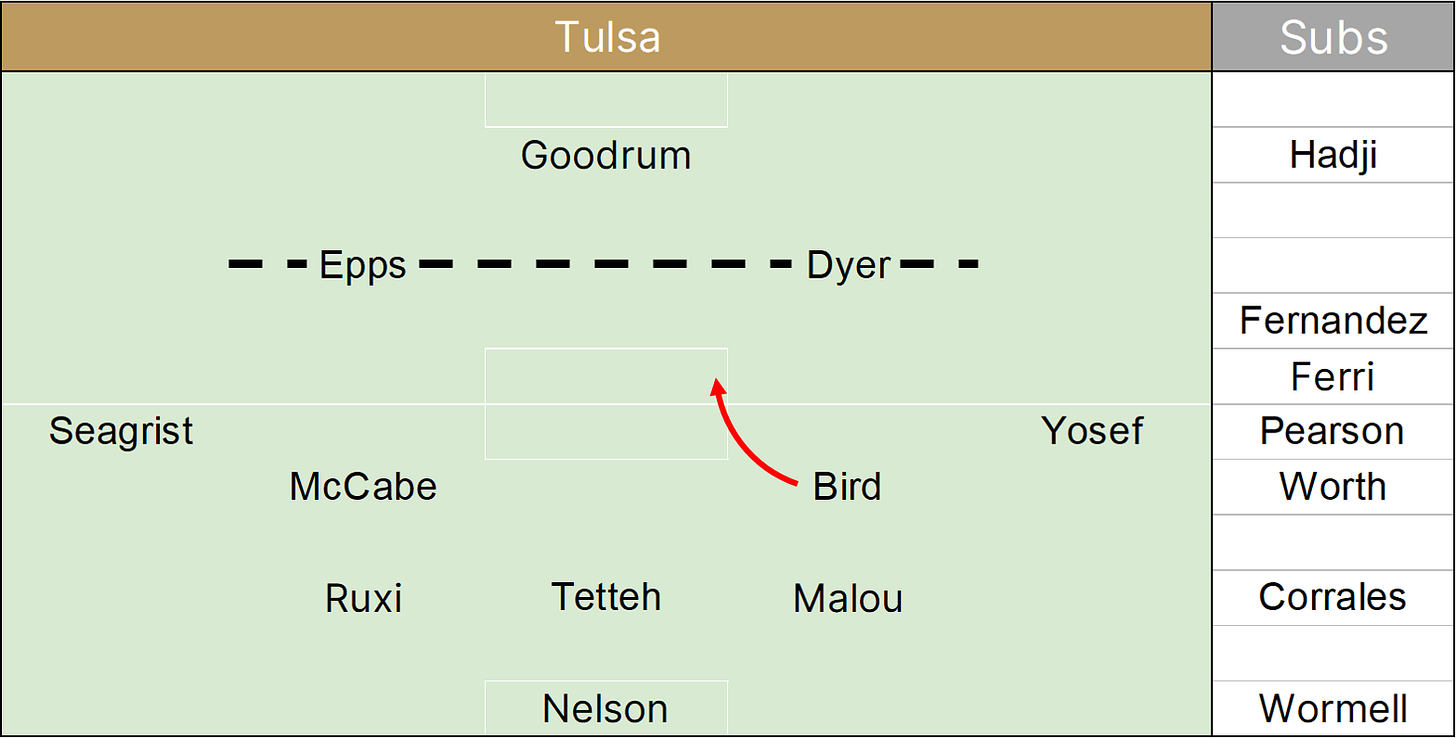

FC Tulsa

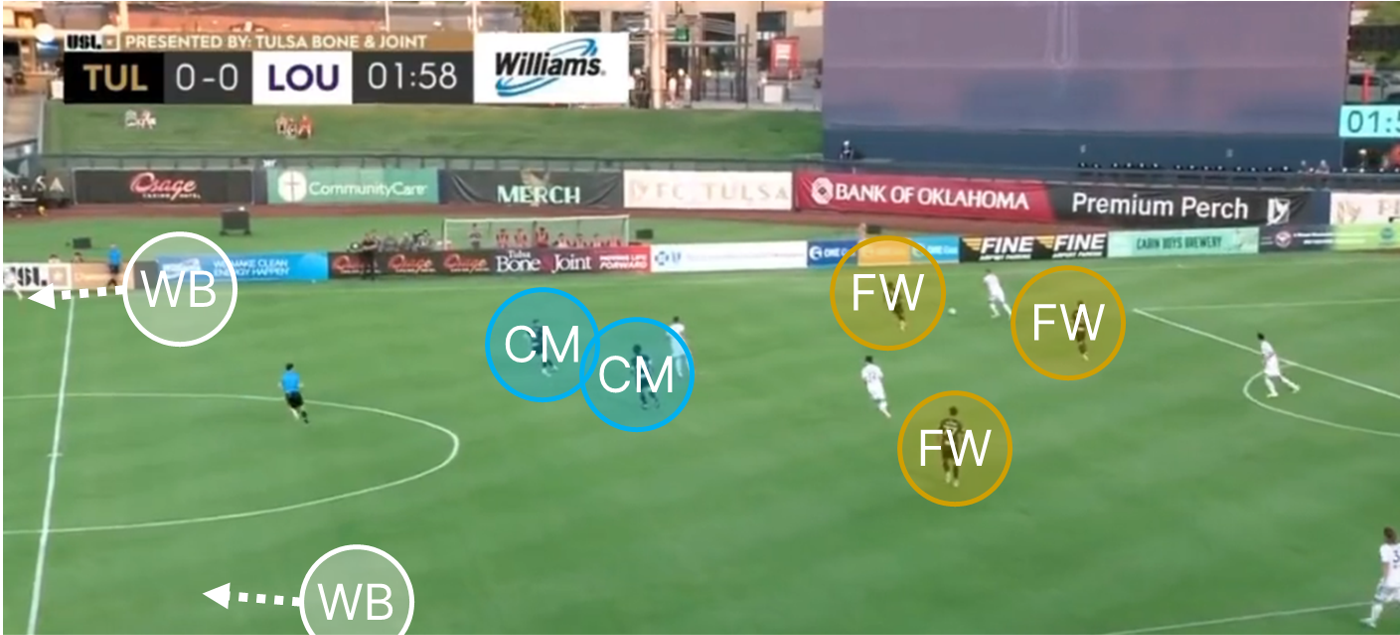

In the wake of injuries at the back and trades for Phillip Goodrum and Patrick Seagrist, Tulsa settled into a 3-4-3 with very aggressive wing backs and a possessive style in build.

Marcus Epps tends to roam wide as a forward, whereas Moses Dyer makes secondary, strikerly runs off Goodrum. In doing so, Dyer opens up overlaps from Milo Yosef and allows one of the CMs to step up and take on a distributive role.

Build is driven by confident and short play by the three center backs. Ruxi and Justin Malou are allowed to dribble and attempt risky line-breaking balls. Michael Nelson is fearless in connecting back and forth with the defenders nearest to him. As needed, a CM can drop in to create an effective foursome against aggressive presses.

At the back, Tulsa settles into a fivesome with the wing backs very low. Their press is intentionally narrow and tight in a 5-2-3, denying the middle and aggressively closing teams down to win back the ball in dangerous areas.

With Tommy McCabe in the team, Blair Gavin has also experimented with a more fluid shape. McCabe plays as the centermost member of the back three without the ball but steps into a 4-1-2-3 in possession. This system encourages aggressive overlapping down the flanks and lets the No. 6 shine as a passer.

Within a 4-2-3-1 shape in which they began the year, Tulsa employed the most active wingers in the USL. Marcus Epps and Milo Yosef were expected to press into the forward line against back-three build but could also drop low to interchange with the full backs in block. The press was aggressive, compressing one winger and the striker into tight windows to corner opponents.

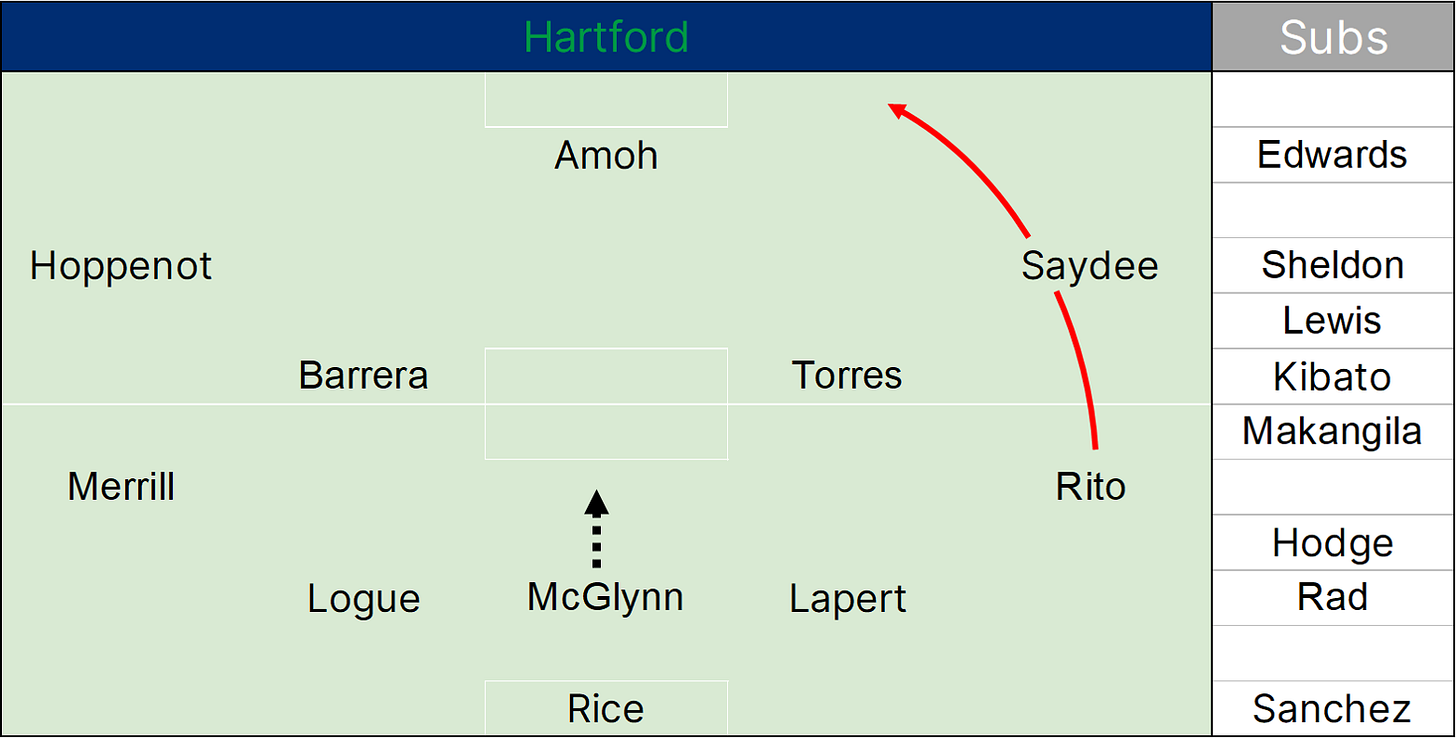

Hartford Athletic

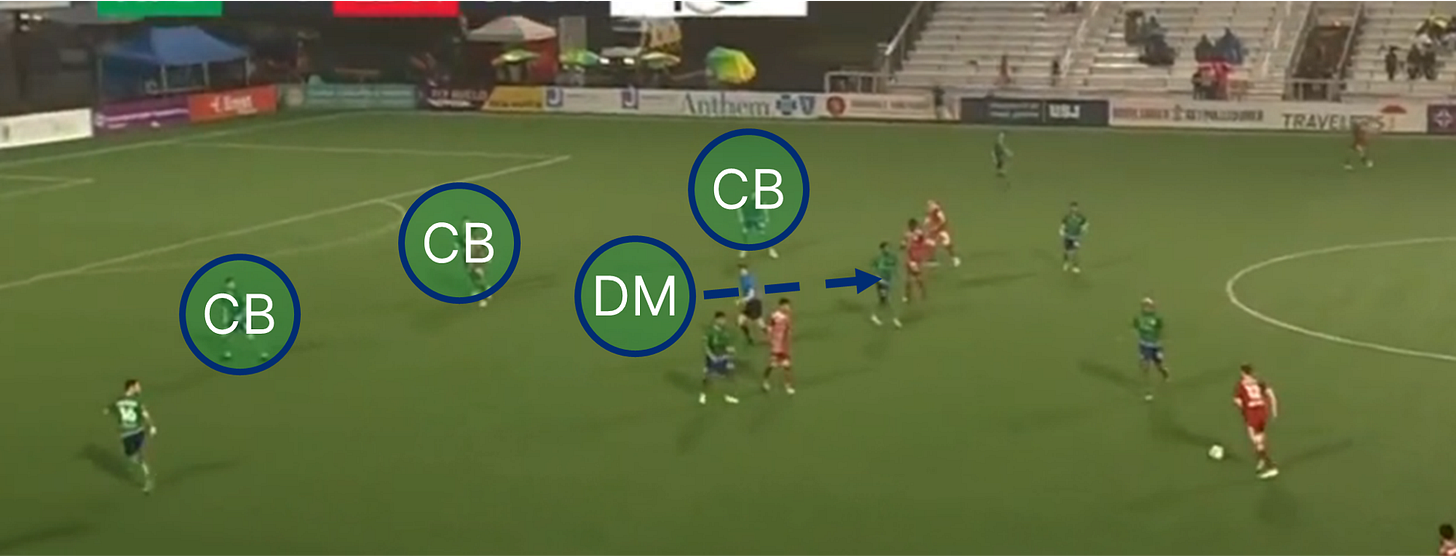

Regularly changing formations, Hartford’s preferred look seems to be a 5-2-3 or 5-3-2. The height of the back line off-ball is rather standard, and the philosophy in the press leans toward “denial” rather than “intervention.”

Conor McGlynn, a natural midfielder, is the centermost member of the back three, and he often steps up a line to make stops with two teammates behind him. Niall Logue, often the left-sided center back is liberated to carry the ball in possession.

The team’s shape in the midfield is variable. Ramos uses one proper No. 6 but never doubles up to forge a defensive-minded pivot, leaning towards the use of two No. 10s more often.

The forward line is expecting to rove and provide width. This aim is natural with Antoine Hoppenot and Prince Saydee, two quick and creative wingers, up top. Especially with the midseason acquisition of Edgardo Rito, this width proved successful at bending defenses.

Hoppenot has also been used as a wing back at times, dropping deep when out of possession before bursting into a proper winger’s role when Hartford regains. This moves the team’s shape into more of a 4-3-3 or even a 3-3-4 depending on Matt Sheldon at the right.

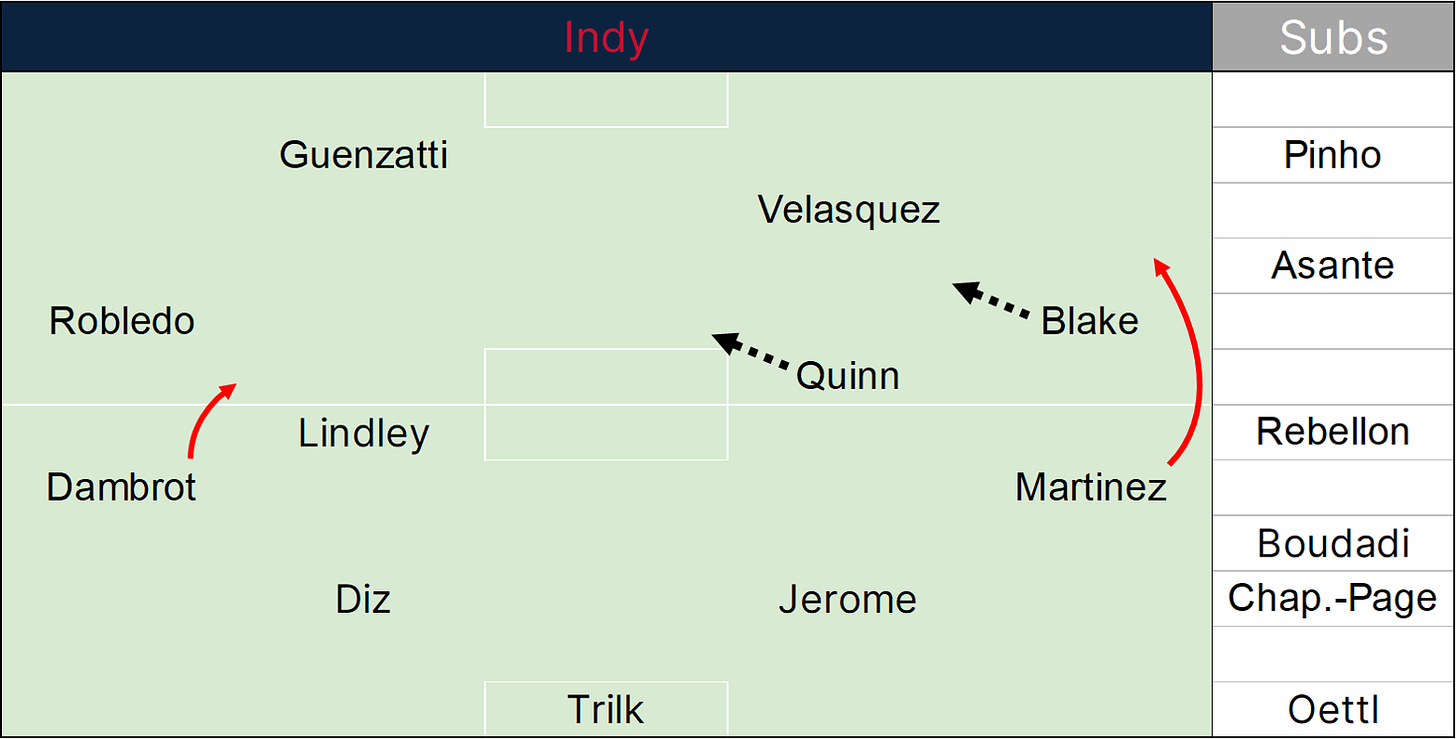

Indy Eleven

The Eleven began the year iterating upon a 4-4-2, using a diamond-shaped foursome with Solomon Asante often at the tip of the midfield. A flatter line with Aodhan Quinn narrow on the left and Asante very wide on the right can also prevail.

Most recently, Indy turned to that flatter 4-4-2 as a base shape, using Jack Blake as a narrow winger and allowing the right back - either converted striker Douglas Martinez or proper full back Younes Boudadi - to aggressively overlap. The Eleven sometimes doubled up, using two narrow wingers in that manner.

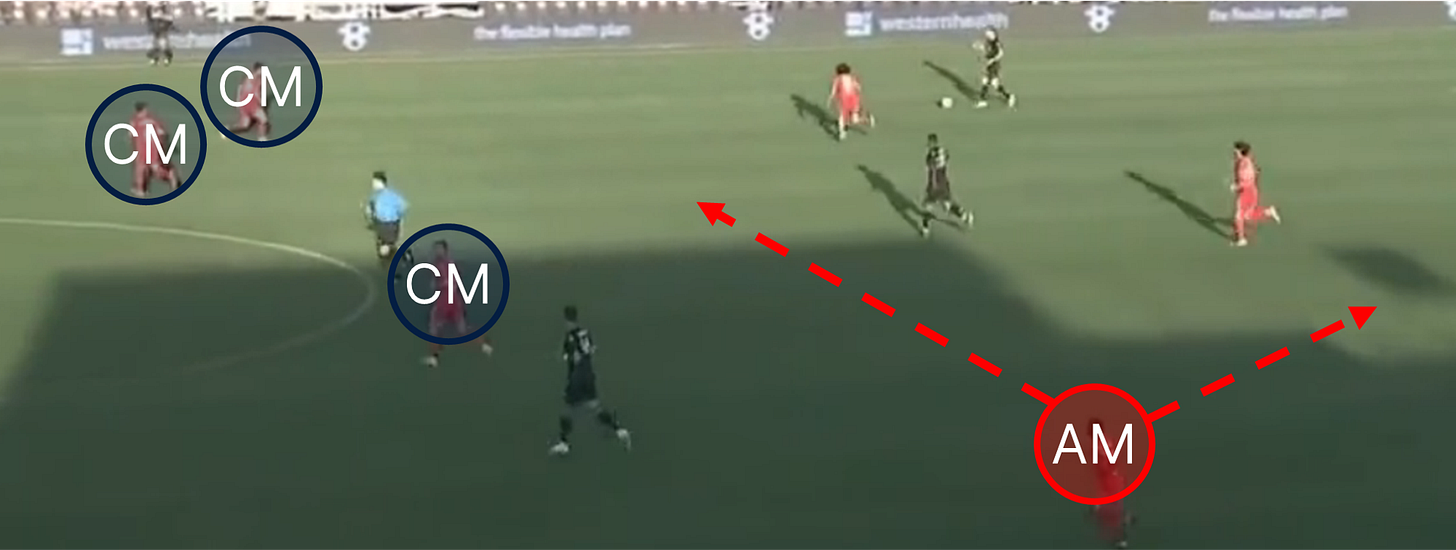

Moderate-to-light in the press, Indy often man marks opposing midfielders to deny build. None of the Quinn-Jack Blake-Cam Lindley trio is especially aggressive in the tackle, and Lindley tends to sit deepest of all in front of the center back pairing.

Indy dominates possession thanks to short passing patterns, beginning in goal . Their moves drive down the center of the park, allowing for the full backs to aggressively advance. Robby Dambrot takes especially high positions and underlaps more often than not as compared to the right-siders.

With the ball, Indy’s forwards regularly drift into the hole, engaging in interchange with CMs and holding up possession. The style tends to be low-tempo.

As the season wore on, the Eleven moved into more of a 5-3-2 with Jack Blake as the right wing back and Martinez as a mobile, roving forward up top alongside Sebastian Guenzatti. Occasionally more of a 5-4-1, the shape gave the side much more width across the board.

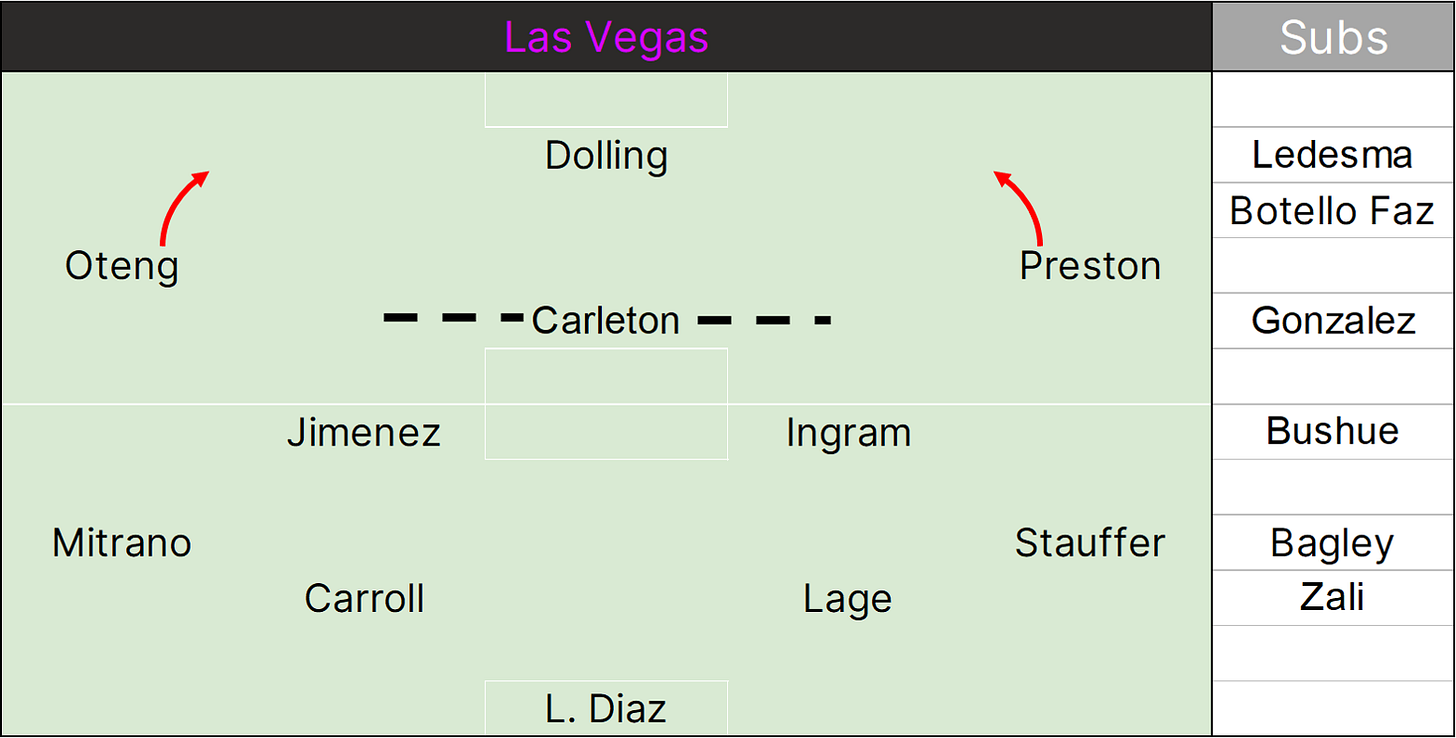

Las Vegas Lights

The Lights, while varying their attacking look, systematically drop deep into banks of four players when defending in block. Their defensive line is unaggressive and tends to sit low.

If the Lights can counter out of their deep block, they are able to activate a diverse set of wingers. Preston Tabortetaka and Eric Oteng are more pace-forward options; their threat on the run can force opponents deep, thereby opening the midfield for Andrew Carleton’s vital creation.

When in possession, Las Vegas is the most direct and vertically-oriented team in the USL in terms of restarts and long passes. Their modus operandi is to hoof the ball long, tuck their wingers narrow or high, and break through the quick decision-making of Andrew Carleton and the like. That narrow shape can appear as a 4-2-2-2.

Andres Jimenez serves as a do-it-all destroyer and ball recycler as a No. 6 in a low-possession Las Vegas teams. His interventions define a team that seeks to disrupt rather than regain. Next to him or alternative holder Jacob Bushue, Justin Ingram remains an underrated ball-mover as a more advanced No. 8.

Loudoun United

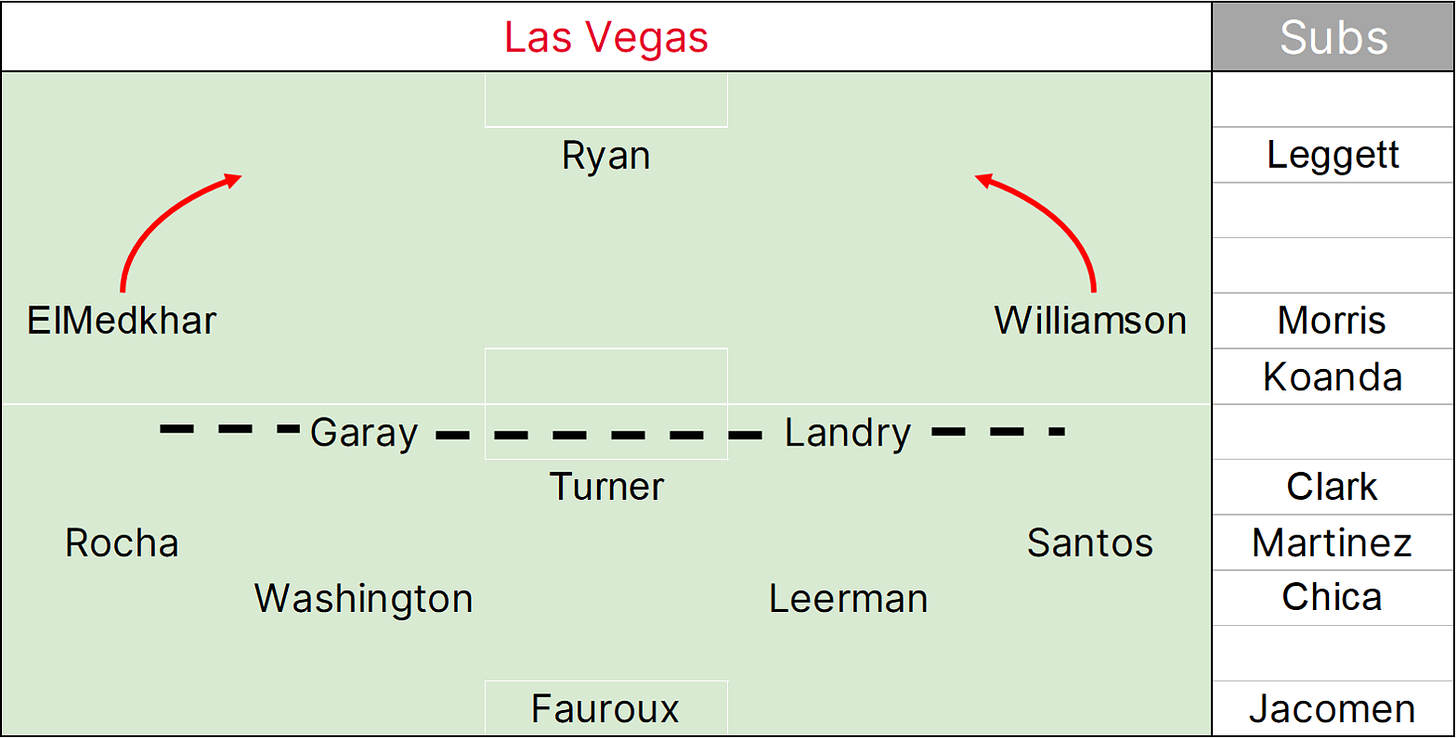

Ryan Martin’s Loudoun is high-flying in the press, showing great aggression in the forward and midfield lines out of a basic 4-4-2. The wingers and fullbacks - think Koa Santos - close high and hard, and the aggressively-placed central defenders are instructed to close towards the halfway line to clamp down on breaks. These same principles apply in a 4-3-3 hybrid shape that leverages Tommy Williamson and Kalil ElMedkhar as do-it-all wingers alongside movile striker Zach Ryan.

In block, Loudoun flattens into a deeper 4-4-1-1 or even 4-5-1. This lets the team clamp down in their own half and liberates a lower forward to drop in to pick up the ball to shepherd breaks.

Beginning the year with Gaoussou Samake as a proper left back, Loudoun lost him to a loan recall and experimented with a back three. After struggles with spacing behind the wing backs, the club received defensive loanees from the old parent, DC United, that allowed for a return to normalcy.

When Loudoun is clicking, they often push both forwards into one channel to bend the defense and open up space down the middle or for a cross-field switch. The wingers regularly carve inside behind these rotations, showcasing Loudoun’s fluidity.

In the middle, Loudoun’s pivot stays somewhat deep and defensive, though Landry Houssou is improving as a late-arriving runner from the central midfield. These CMs are expected to cover behind full back overlaps, important given the fluidity and verve of the wingers in this team that preclude instant defensive recoveries.

Louisville City FC

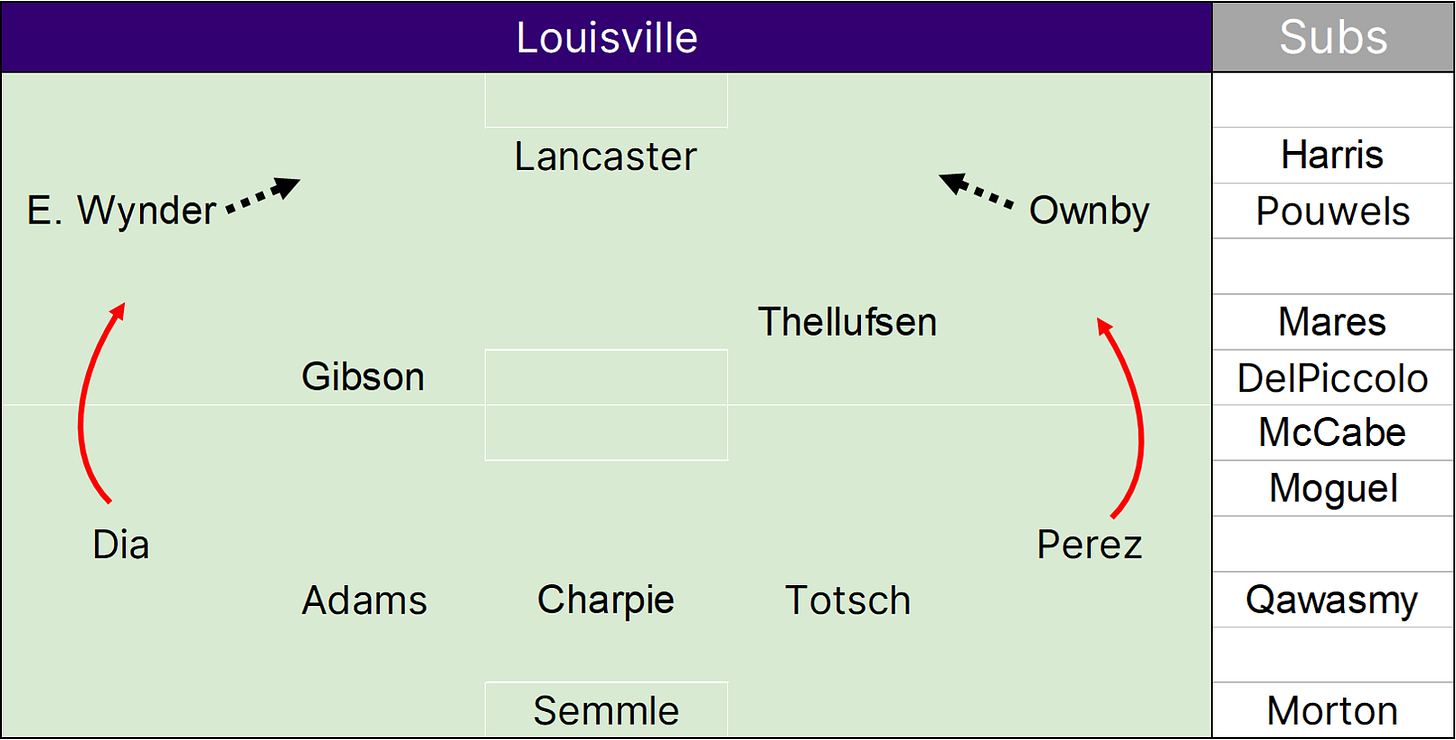

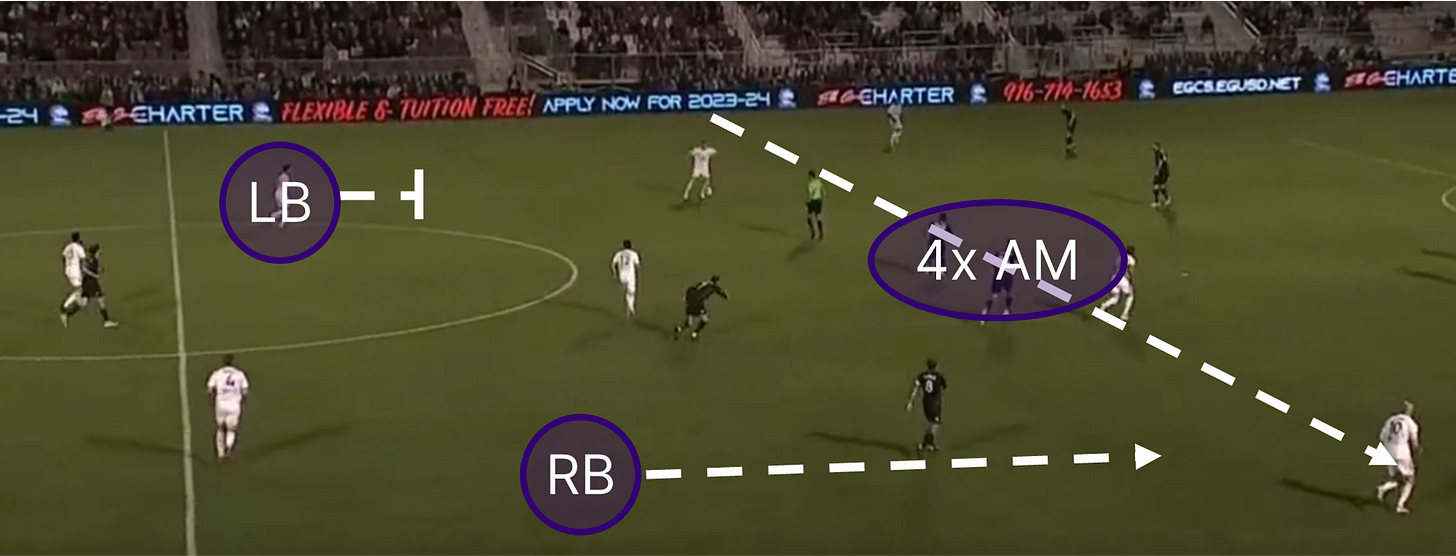

After trading for defender Kyle Adams deep into the season, LouCity moved to a 3-4-3 shape built on the interchange of two mobile attacking midfielders and the aggression of the wing backs. Adams and the other defenders were liberated to carry the ball, though the approach was generally very direct and not very focused on possession.

Reprising a well-worn 4-3-3 or 4-1-4-1 shape at the season’s start, Louisville was and is noticeably less hard-edged in the press. They occasionally invert the shape of their midfield to push the central midfielders up next to the striker while deepening the wingers, but their press is mostly more measured. Their counterpress has also become noticeably gentler this season.

Even so, this team continues to employ a very high back four that compresses the field. Sean Totsch anchors the defense with great aggression in the tackle, covering behind the often-advanced Manny Perez at right back. The back line is shielded by a low-seated No. 6, most often Tyler Gibson.

In build, Louisville has iterated on the usual formula by keeping one full back deep. This most often means that Amadou Dia sits lower, ceding space for roving runs by the attackers. Additionally, LouCity uses their most creative CM on the left, so the personnel choices are designed to give that player maximum room to operate.

On the other side, the right back is expected to push up and provide width alongside Brian Ownby on the wing. Ownby regularly carves towards the box, filling for or interchanging with the proper striker. Still, these actions tend towards the sideline more often than not, leaving Louisville a shade undermanned in the center of the park at times.

Memphis 901 FC

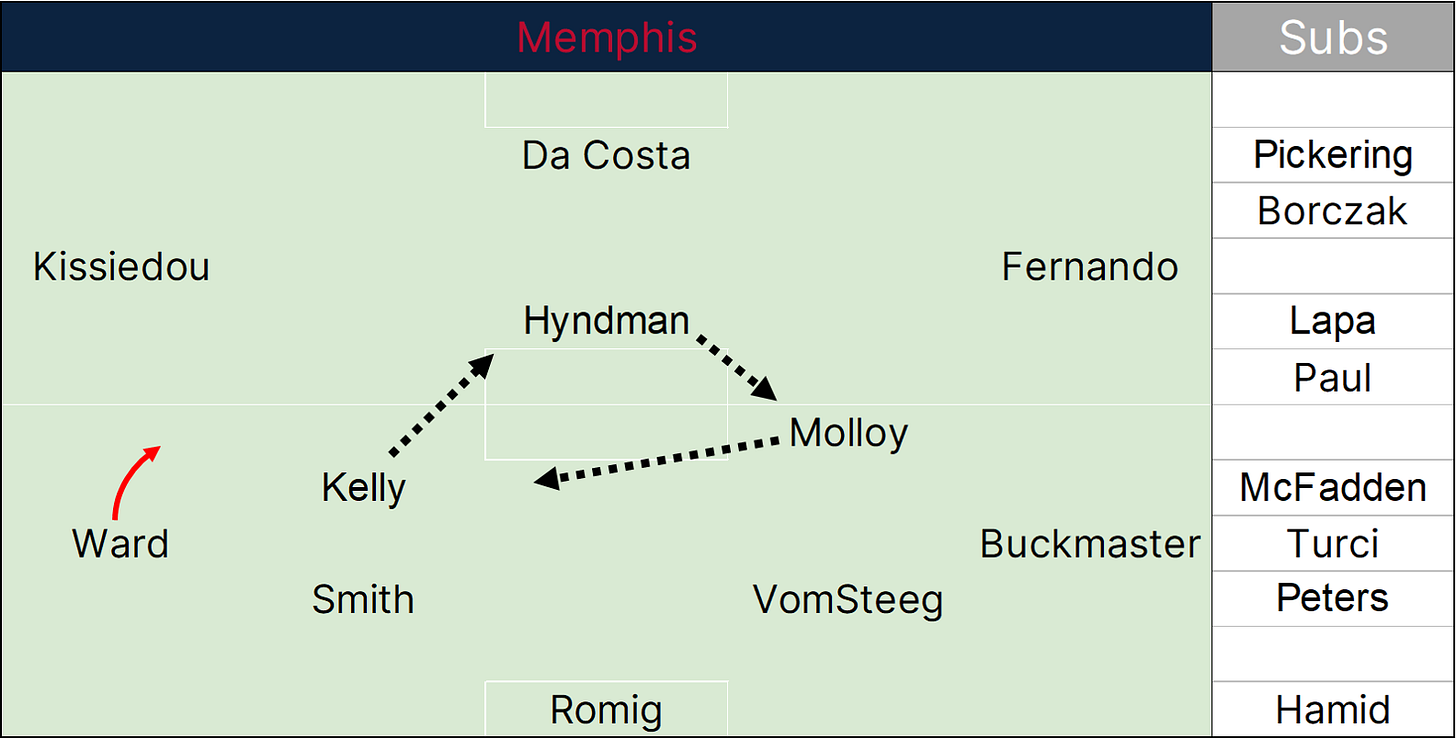

Under Stephen Glass, Memphis has retained their 4-2-3-1 shape while becoming more pragmatic on the ball. They own a good share of possession thanks to a technical midfield, but their press is not focused on high action. Memphis does focus on fiery recoveries and counterpressure, pushing one central midfielder and the full backs far up field to keep the offensive zone.

Without employing a true No. 6, 901 FC expects their CMs to take turns covering in front of the back line. Rece Buckmaster, the more conservative of the FBs, can often tuck deep and narrow to serve that same purpose in certain situations.

While attacking, Memphis splits their CMs into a 4-1-4-1 to pin opposing midfielders in bad positions and open up passing triangles. The skillful movement of Aaron Molloy and Jeremy Kelly effectively allows this team to deny foes the ability to stay flat and compact. Emerson Hyndman has entrenched these trends.

Glass inverts both of his wingers as a matter of principle, and the narrowness that the ensuing in-cutting provides opens up ample space for overlapping, especially from Akeem Ward. Memphis’ lone No. 9 is expected to run and cut aggressively to drag the opposition out and create space for these wingers, who lead the offensive charge in this side.

Miami FC

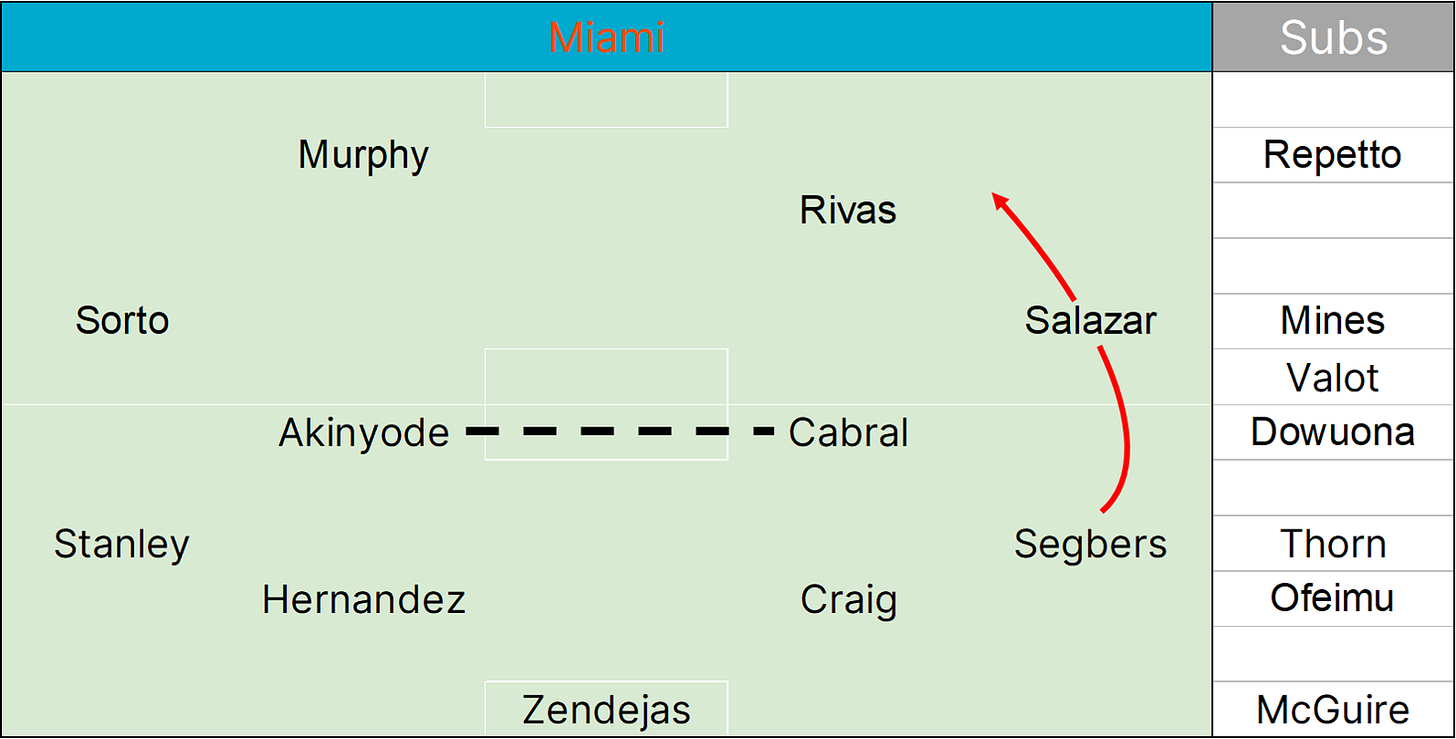

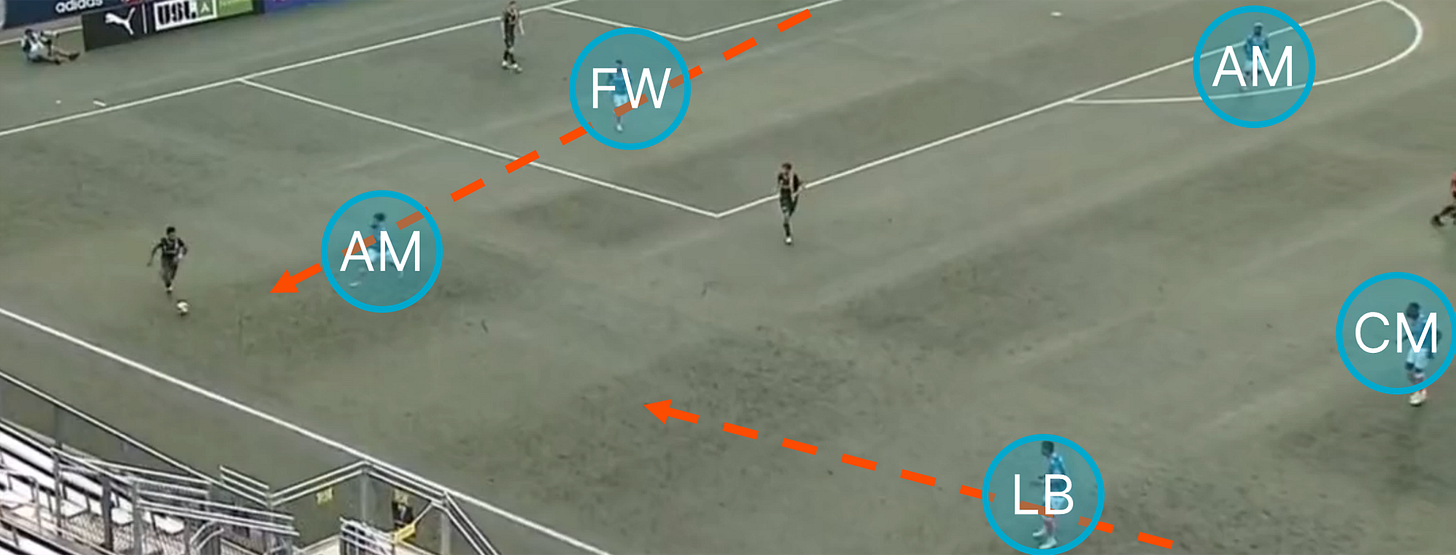

Lewis Neal’s Miami use a 4-4-2 or 4-4-1-1, a system that features Mark Segbers’ overlaps on the right as a cornerstone of their offense. The right back pushes up, allowing a second striker and right winger in front of him to interchange and make supporting runs into the box behind another No. 9.

Centrally, Bolu Akinyode is the anchor as a proper holding midfielder. Occasionally joined by another No. 6, Akinyode has recently been partnered with a more typical box-to-box player in Gabriel Cabral, though a diamond can come about if Florian Valot is in that slot.

Before moving on from Anthony Pulis, Miami had upped the intensity of their 3-4-3 or 3-2-5 press by relying on the athletic the wing backs to close windows and force riskier passes from the opposition. At back, they relied on the interventions of wide center backs to clean up in the channels.

Up top, the aforementioned 3-2-5 look was often the baseline for Miami, starring a noticeable level of interchange between the WBs and AMs in the system. When incision lacks, Miami moved into an unbalanced 2-3-5. One of the wide CBs - most often Stanley - advanced into the midfield line while the WB on the opposite side hedged deeper. This give-and-take shifting bent opposing defenses to create overloads in the half spaces for Miami.

Monterey Bay FC

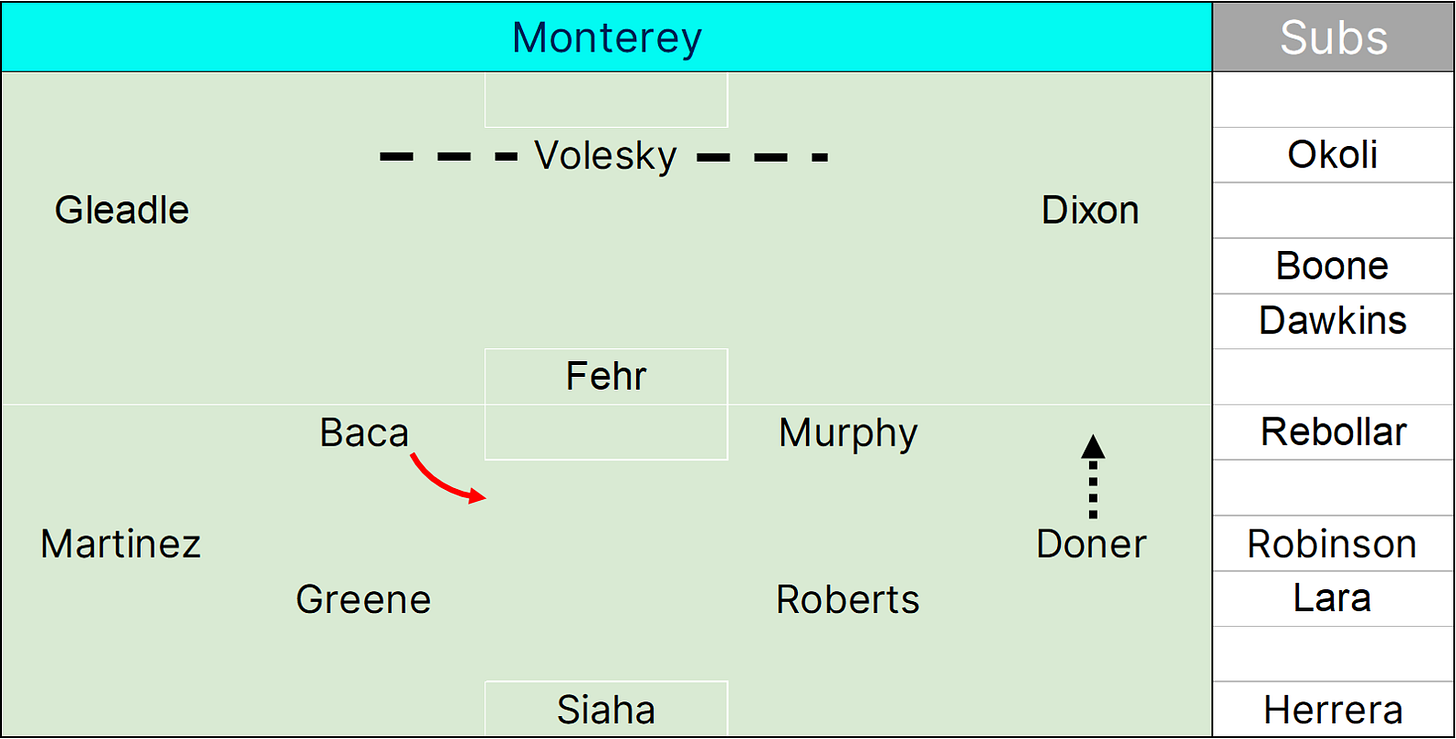

Monterey’s game is defined by an intentional, low-action sort of soccer. The side sits in deep in a 4-4-2 or 4-5-1 out of possession, packing tight in their own half. Accordingly, the side plays a rather low defensive line and tucks their full backs narrow while defending, expecting the wingers to track back as wide supports.

Still, Monterey is quite aggressive within their half. Hugh Roberts stays lower as an anchor, but his center back partner regularly pushes up in the tackle. In those moments, the FBs must fill centrally. Rafael Baca can also do the job, rotating into defense.

When building, this team is very direct, especially on restarts. The attacking shape tends toward a 4-2-4 or 4-3-3 look, and the midfield pivot aggressively attacks loose balls off of long goal kicks to put themselves on the front foot.

Once established, Monterey becomes very fluid in their motion. Christian Volesky is the static, hold-up-focused pillar around whom attackers like Sam Gleadle and Alex Dixon rotate. These flanking attackers often try to overload one channel while bolstered by FB overlapping.

Counterattacks are also crucial for Monterey. Speedy wingers and a preference for long balls make this team very effective at beating opponents before they can set up in their defensive shape.

At points, Monterey experimented with a back three in which creative No. 8 Mobi Fehr joined the back line. The choice was effective in that it allowed full back Morey Doner to more liberally advance into the offensive half.

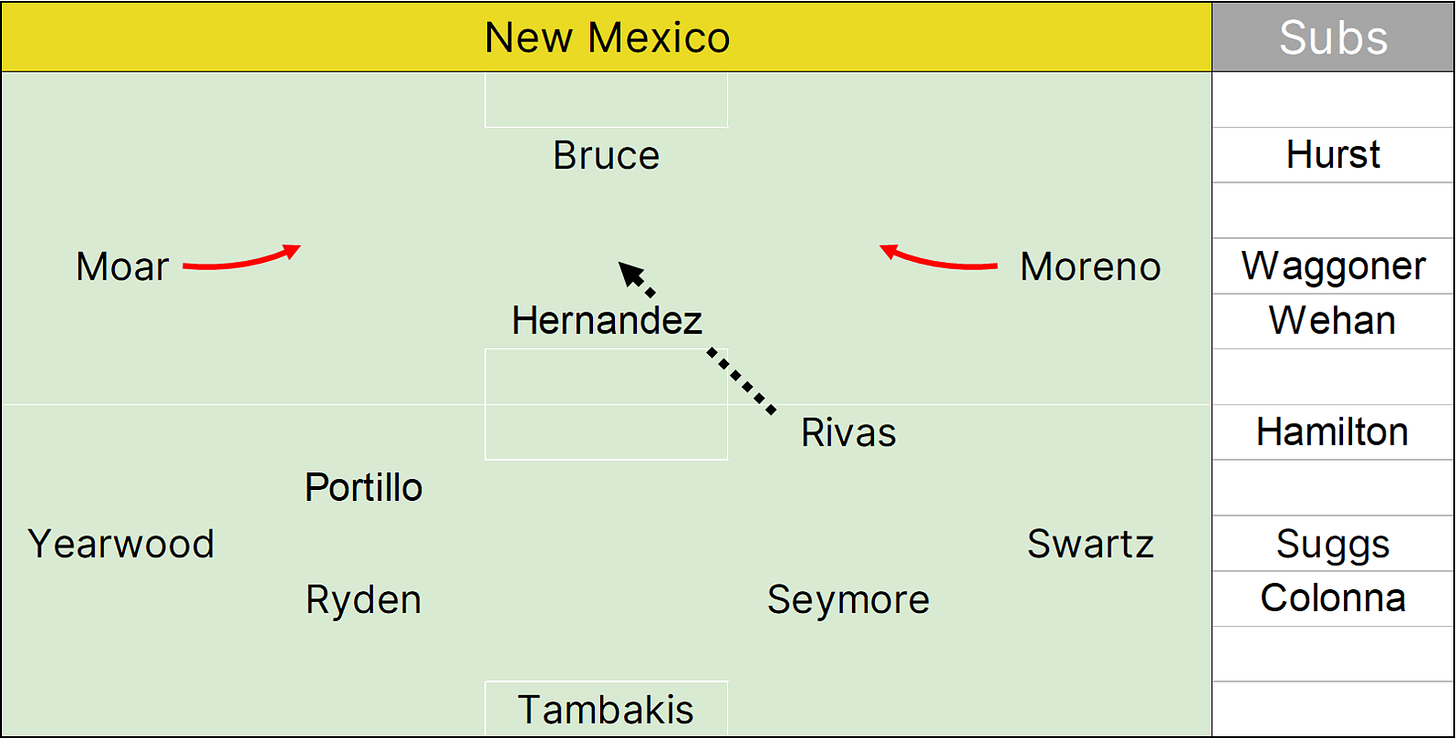

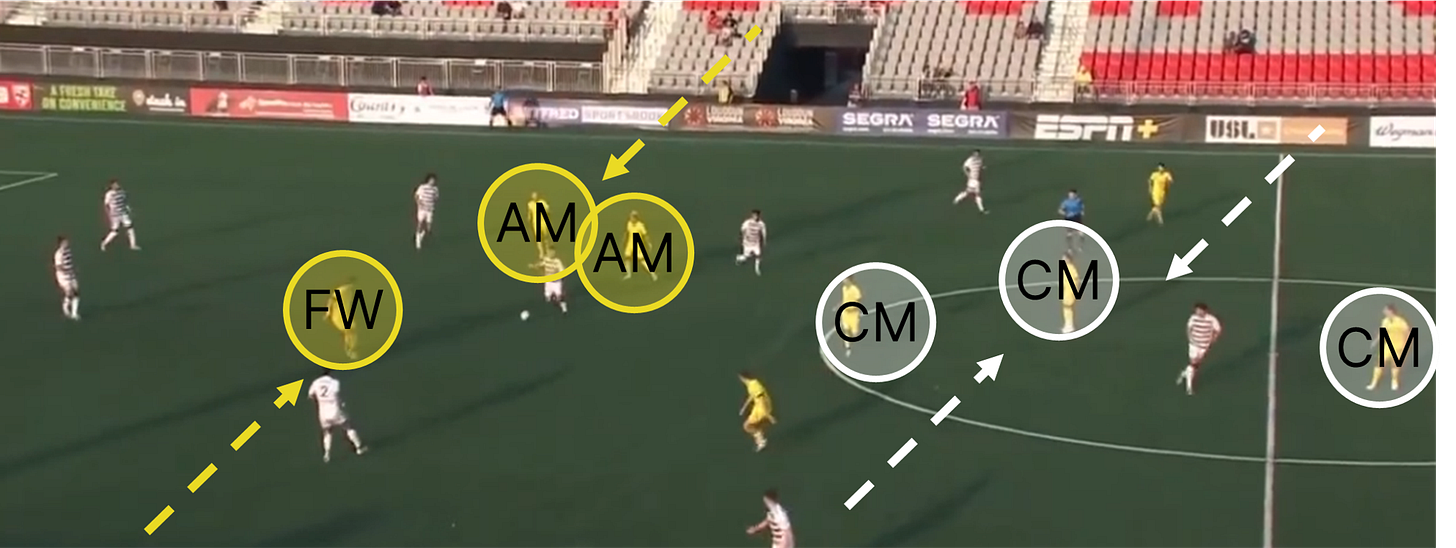

New Mexico United

Though they’ve dabbled with back threes, New Mexico bases their system out of a 4-2-3-1 shape. Narrow wingers often compress against opposing pivots in build, and the No. 10 can press up to bolster this aggression or sit back as a lane denier. Either way, this is one of the harder-edged teams in the USL off the ball. Moving Daniel Bruce, a natural FB, to striker has compounded that phenomenon.

Pair that front-line fire with a very aggressive and interventionist pivot, and New Mexico is rendered a very aggressive defensive unit. Even so, their center backs tend to play at a middle height, and Justin Portillo is more of a deep creator than a destroyer as the No. 6. However, his pivot mate - usually Sergio Rivas - is incredibly active roaming the pitch to recover the ball and open passing lanes.

In attack, New Mexico’s wingers tend to be ball-dominant and love to take on opponents on the dribble. The low-percentage nature of take-ons and the aggression of this club’s defensive system make for an end-to-end game, and New Mexico leans into this fact by employing a direct passing profile in build. Second ball wins are paramount.

When settled in the final third, the full backs advance up field but tend to sit further back and whip in crosses from deep. In these situations, the No. 10 regularly makes runs to the near post, arriving late to meet these crosses against a defense that has already adjusted against the striker and wingers.

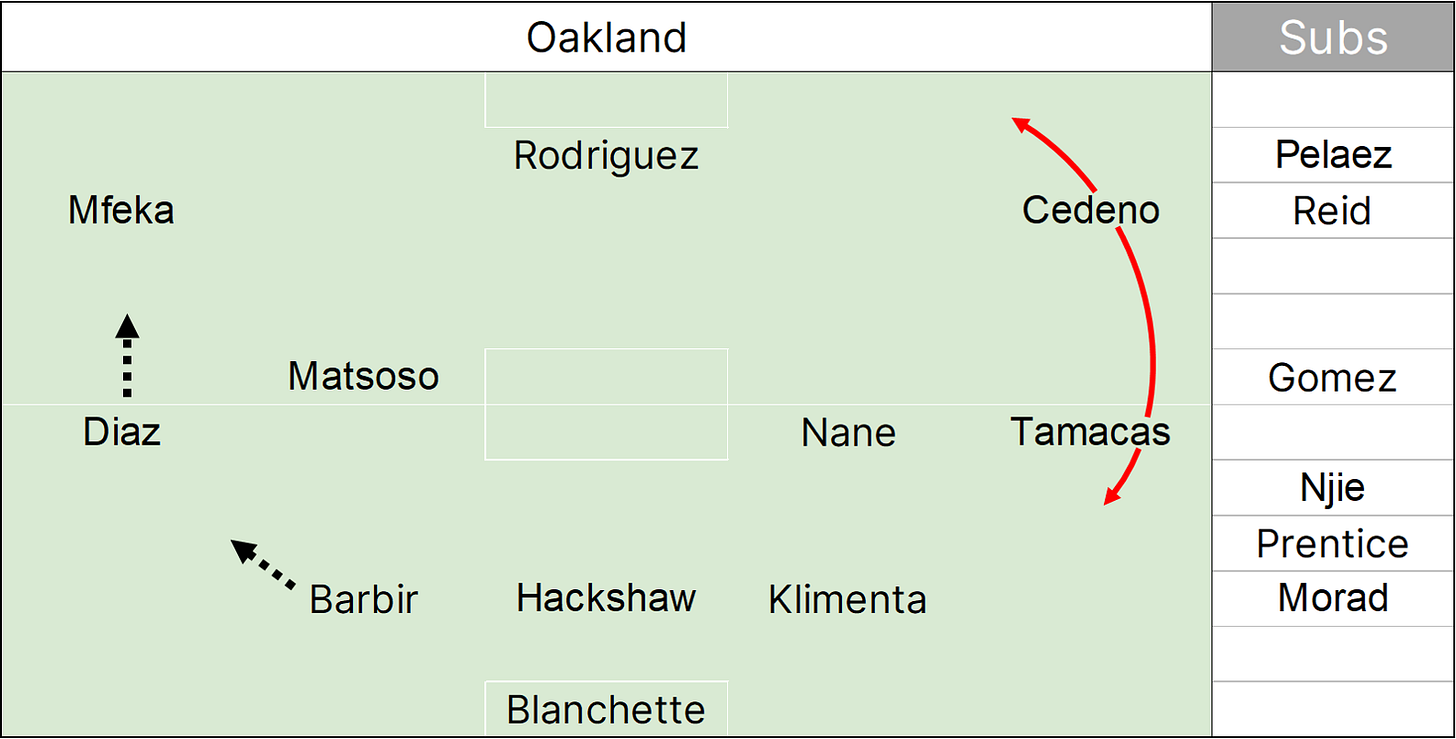

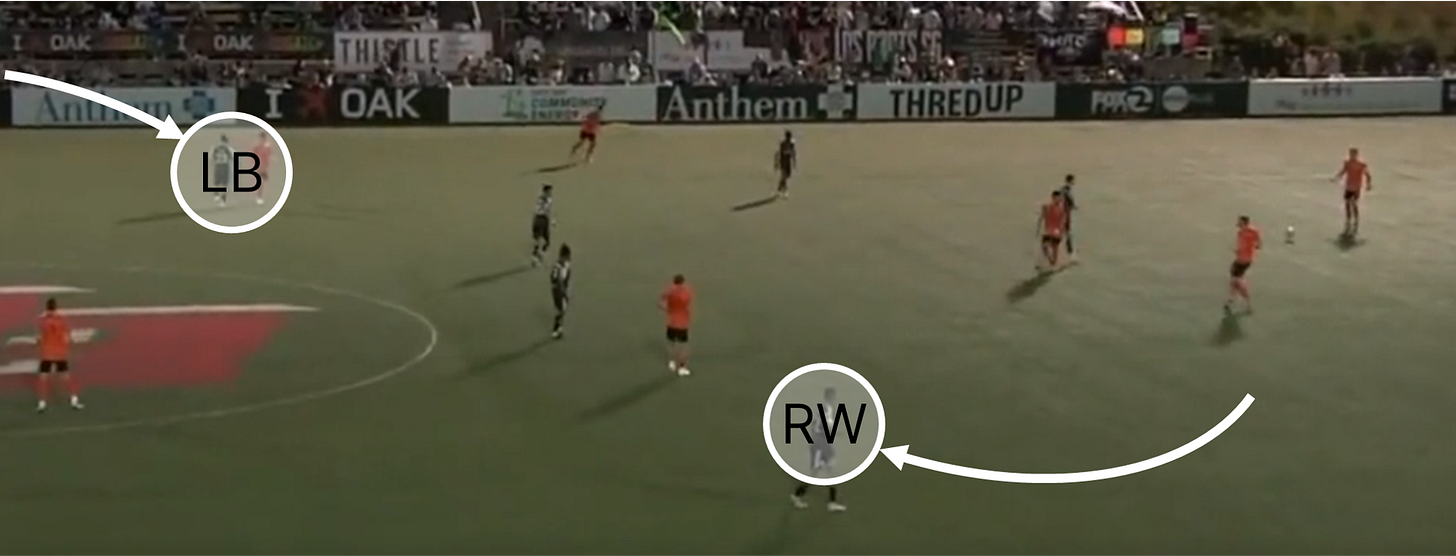

Oakland Roots

Oakland’s 3-4-3 is very aggressive at the central defensive spots, using the wide defenders as hard-charging closers when out of possession. The Roots are less aggressive up top in 2023.

Before he was sold, Edgardo Rito sat deeper on the right flank than Lindo Mfeka or any other left-sided counterpart. The broad strokers of those tenets have remained because of Jeciel Cedeno’s emergence as a right midfielder and narrow forward depending on phase; he allows for Oakland to form a defensive 4-4-2 by dropping low while left wing back Memo Diaz coming high.

A two-man pivot underlies the system, pairing two roving, box-to-box types in the spine. The combination can lack width, thus necessitating that aggressive support from the back three. Napo Matsoso is a protypical ball-winner with positive ball skills in that central spot.

Johnny Rodriguez is very active interchanging in the forward line and has emerged as the leading pick in that striker spot. When Anuar Pelaez is healthy, he serves as a traditional hold-up striker. The variety of options there makes Oakland highly flexible within a given match.

Bursts upfield from defenders are crucial as well, creating overloads and wreaking havoc. Danny Barbir on the left is especially adept in this sense, though the phenomenon prevails across the back line.

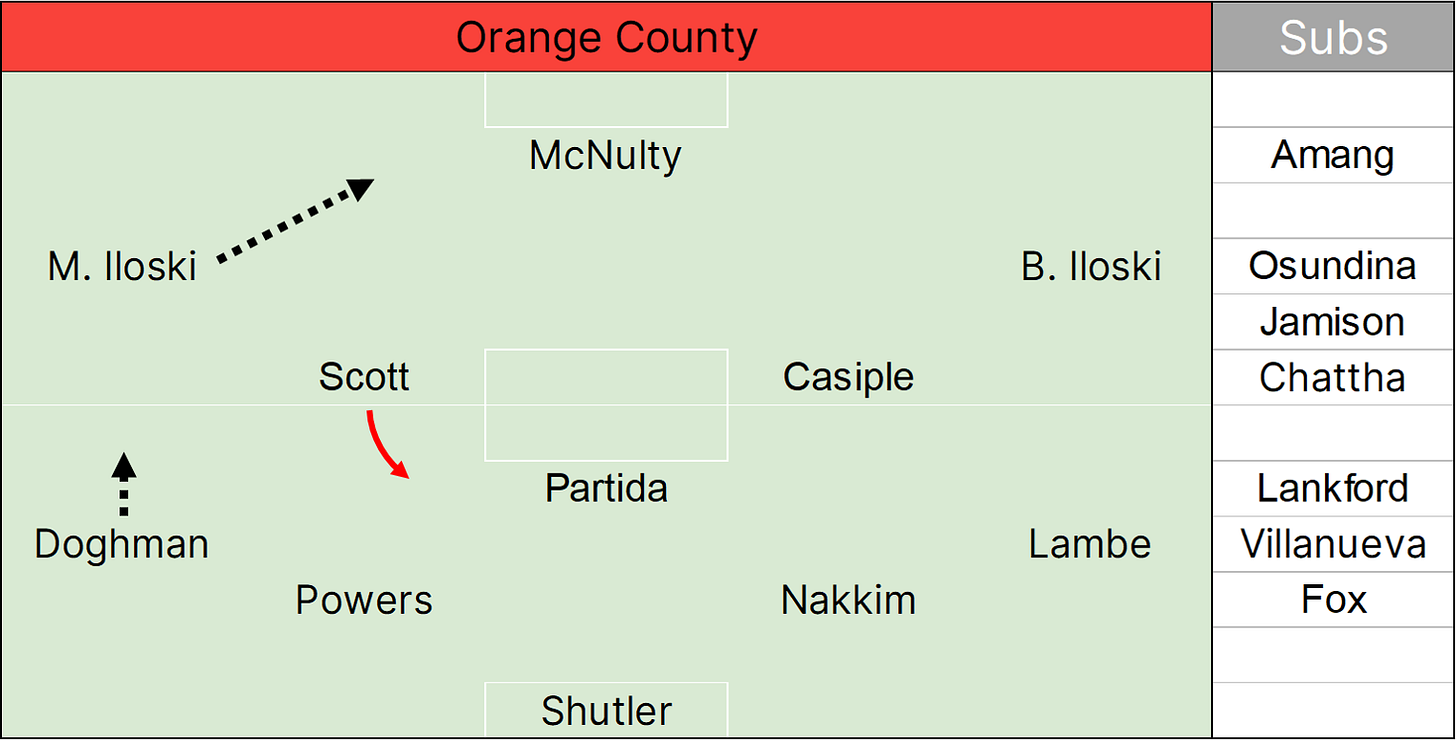

Orange County SC

Under Morten Karlsen, Orange County tweaked their 4-2-3-1 into a much more efficient 4-1-4-1 but continued to defend build with high-charging wingers supported by a fluid central trio. Their back line rests somewhat deep, though left back Ryan Doghman takes a high baseline position.

Though one of the central midfielders can rove behind those wingers, Orange County tends toward a flatter set of CMs. All three close hard when the side is in their defensive half.

In build, the team prefers a longer style, but they’re rather patient. Kevin Partida is the true No. 6 in the midfield, but he’s the stalking horse for Kyle Scott, who drops between or wide of the center backs to ping passes. Lay off Scott, and a defense’s lines are easily broken. Press him, and Orange County will launch it long.

Targeting a physical forward like Marc McNulty, the 2021 champs are thus able to counterpress hard and activate their offense in the final third. There, Milan Iloski - a narrow runner alongside a hold-up No. 9 - can do the job or open up overlapping full back runs.

Opposite, Orange County relies on deeper creation from Brian Iloski as a baseline. Off the bench, they can use Korede Osundina as a wide forward or, more often, call on the end-to-end effort of Bryce Jamison.

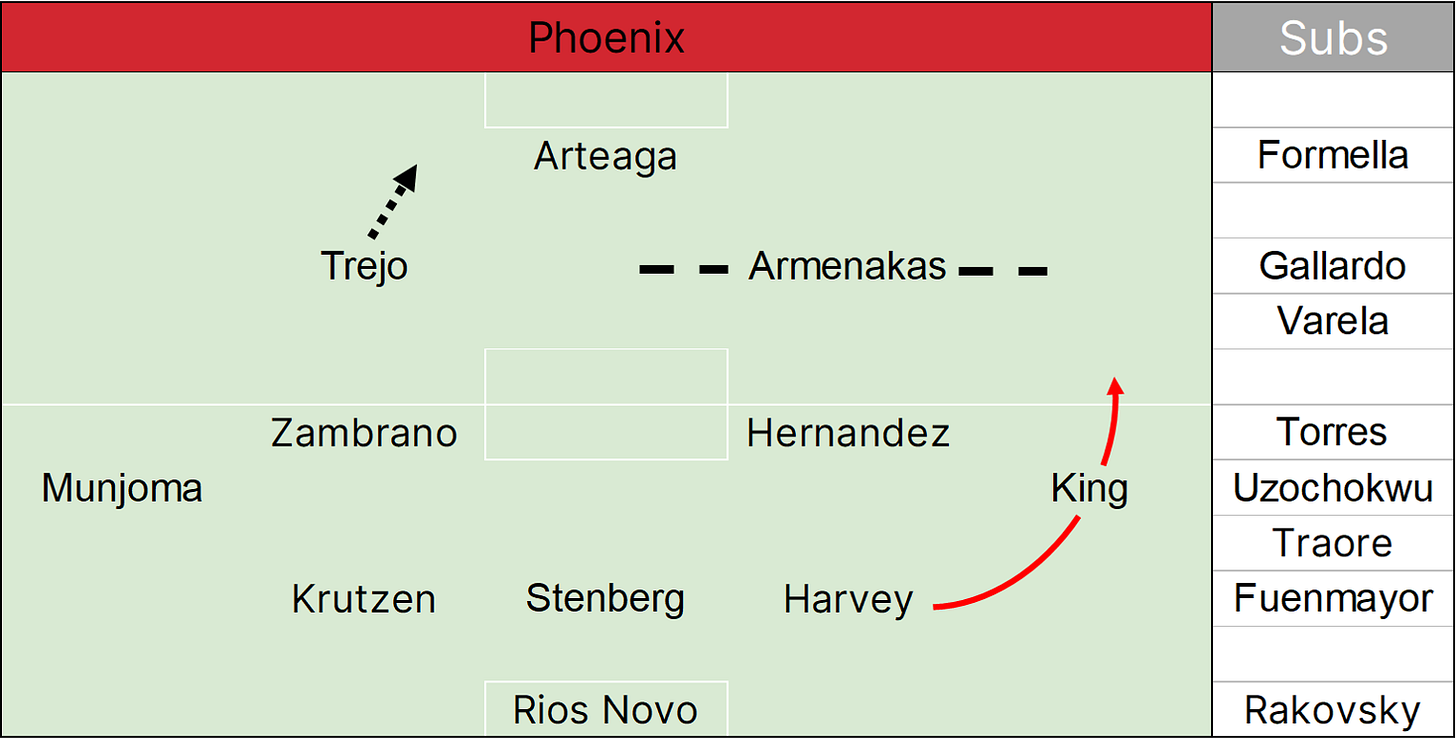

Phoenix Rising

Rising base their tactics out of a back three, defending in either a 3-4-3 or 3-5-2. Daniel Krutzen is the rock of the group, joined by an aerial dominator in the middle and a mobile, ball-advancing right-sider. In the center of the park, Renzo Zambrano is an anchor of a No. 6, joined by a more offensive player.

Ahead of those players, Phoenix presses very high, fanning out into a five-man front anchored by pacy wing backs like Eddie Munjoma and the effort of Manuel Arteaga as the bruising tip of the defensive spear. As with many back-three teams, Phoenix relies on their wide defenders to clean up trouble in the channels.

The shape is always dynamic as Rising build out. Carlos Harvey can be the probing central midfielder that carries the ball with his feet or breaks lines, or he can be the rightmost CB who advances in possession. Darnell King or Gabi Torres advance on the right in a similar fashion closer to the flank. The entire system is underlied by Rocco Rios Novo’s able ball-handling in net.

The aforementioned Trejo typically plays a wing role, and he drops into the flank of a deep-block 5-4-1 with laudable regularity. From that spot, he’s a tremendous ball carrier on the break. Failing that route, Phoenix often looks long into Arteaga’s hold-up at striker before he lays off to Trejo or the tucked-in Fede Varela.

Panos Armenakas has been a major acquisition, lending high levels of intelligence as a runner and awesome incision as a passer to the right side.

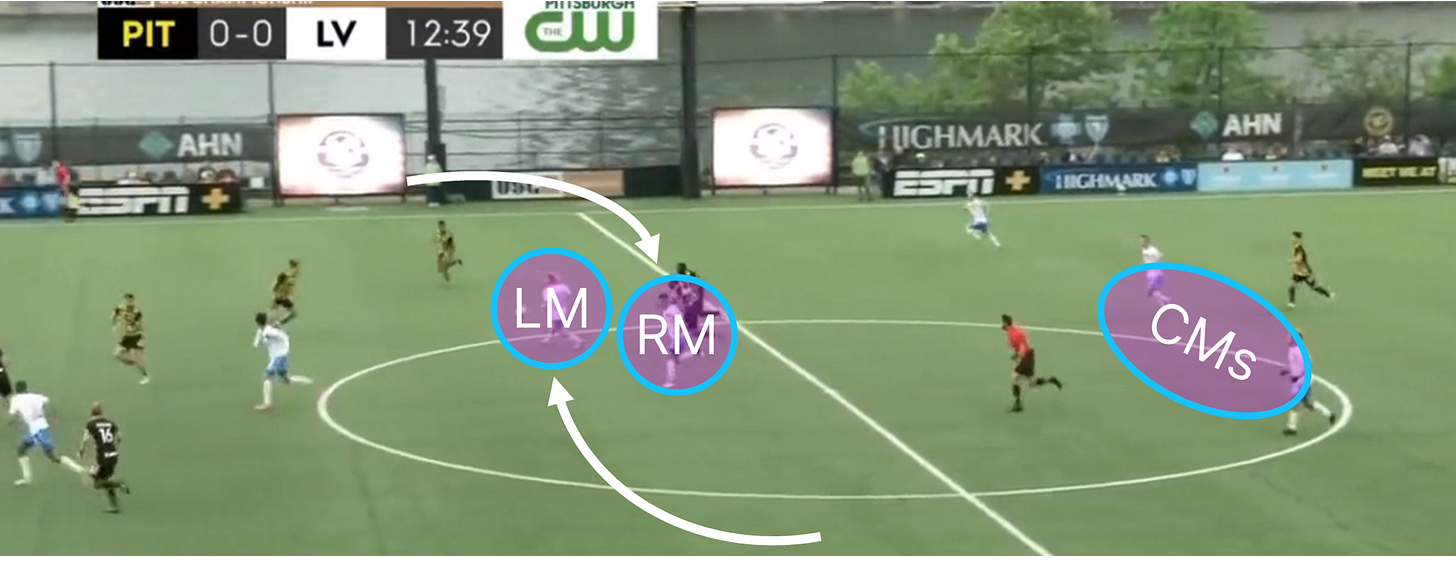

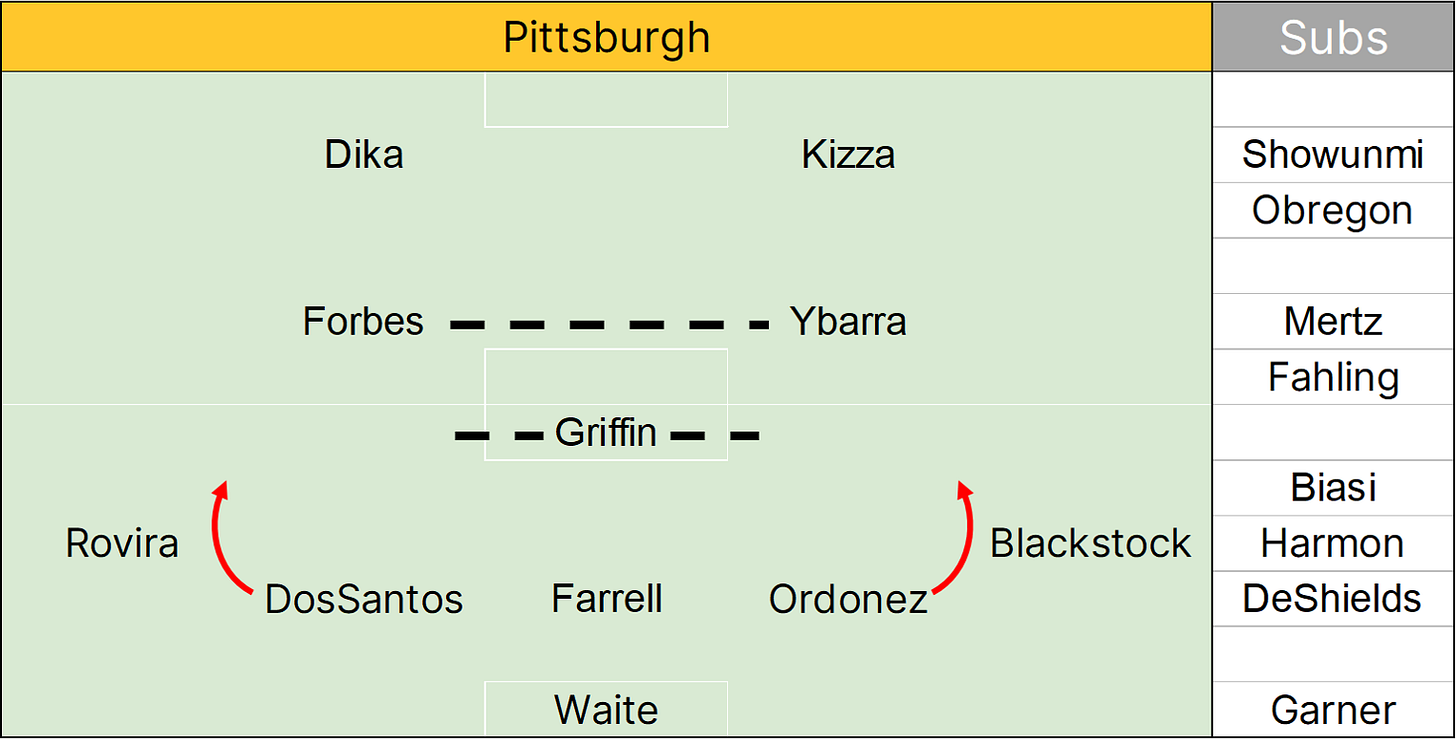

Pittsburgh Riverhounds

The Riverhounds are another consummate Lilley-ball side, prioritizing defense in a true back five that’s harder to pin down in the advanced lines. One true holder - mostly Marc Ybarra or Danny Griffin - sits in front of that line, flanked by two or three other CMs with the freedom to press up or cover to the sidelines.

Pittsburgh uses one or two strikers and an aggressive midfield to ferociously deny the center of the park and funnel opposing build toward the sidelines where the touch line becomes an extra defender. The wing backs aren’t especially highly placed, but, when triggered, close up field apace.

The three center backs in the defensive line play at a moderate height and are active closing to support the midfield against breaks over the press. Arturo Ordonez, a superstar CB, is the best example of a player who understands when to step up and blow up a move.

Fluidity defines the central midfield. Robbie Mertz is most often used on the left, with Forbes central or right. Danny Griffin sits higher and can operate as a shadow striker. All regularly rotate with one another and challenge opponents.

Pittsburgh’s attack drives through Albert Dikwa much of the time. He’s adept in hold-up but has good sense in transition, and his skillset opens room out wide for overlaps or in the hole for those aforementioned midfielders to create danger.

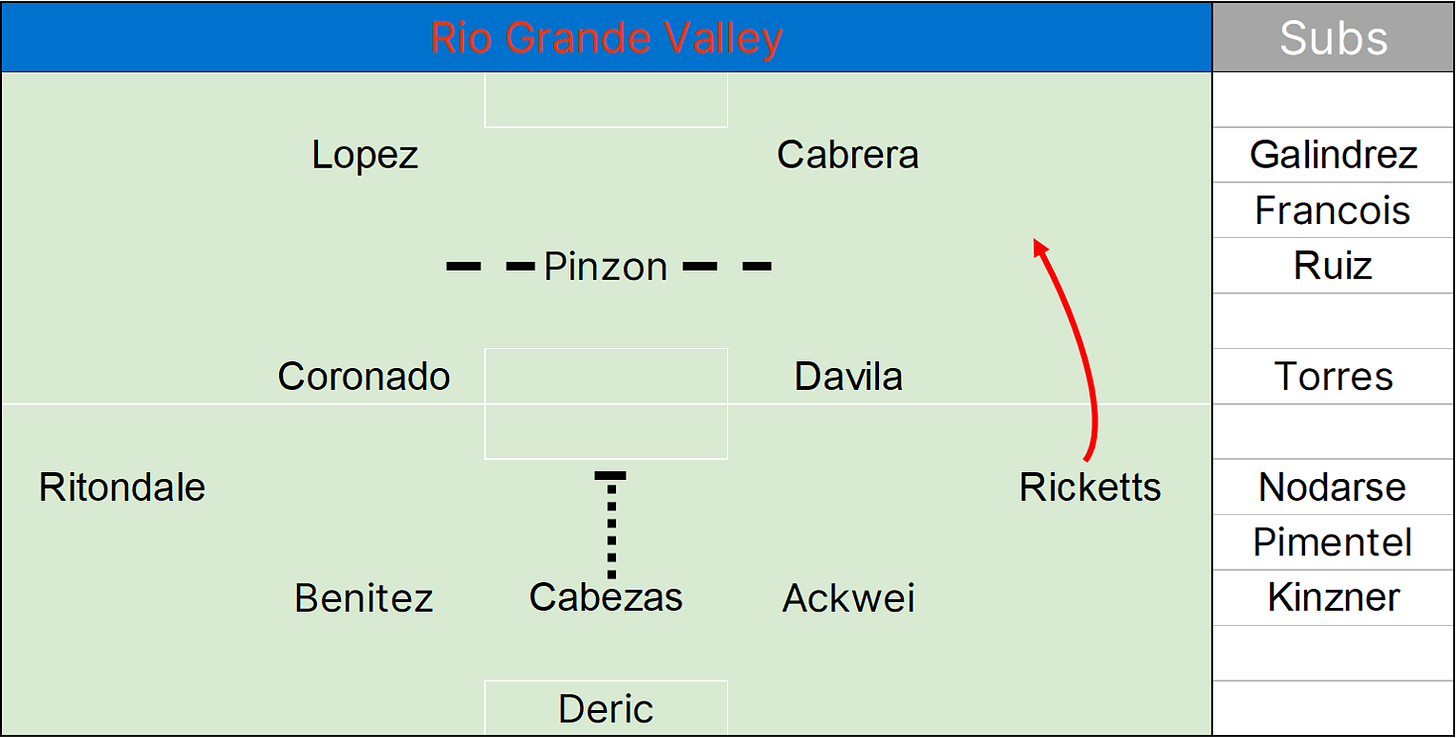

Rio Grande Valley FC

Wilmer Cabrera’s Toros most often use a back three, putting a premium on pace and relying on the technical abilities of Taylor Davila and Jonathan Ricketts on the right to drive offense. Their gravity opens up the rest of the wide Rio Grande Valley pitch.

Early in the year, the side preferred a back four, pressing aggressively in what’s best described as a 4-2-4 shape. More naturally a 4-3-3, the look changed when Davila bombs forward from his central midfield deployment.

Rio Grande Valley’s wingers and wing backs close at angles that try and force moves into the midfield trap, composed of a hard-charging pivot and, often, and advancing defender or two. This effect is most marked down the right through Ricketts and Wahab Ackwei.

Juan Cabezas is the proper No. 6 in the midfield when he wants to be, but his main role is to drop low between the other two center backs to render the Toros’ system a 3-2-5. As needed, Cabrera will push Cabezas higher to chase games.

The attacking line is fluid and mobile. Players like Christiano Francois, Wilmer Cabrera, and Ricky Ruiz combine pace and positivity to interchange and carry the ball at opponents. While this leaves the Toros undermanned in the box, it supercharges them on the break and off of turnovers encouraged by the high press.

Deep crossing via Ricketts, Tomas Ritondale, or a rotated winger can also bear fruit, though the lack of a proper No. 9 can limit the effectiveness of those serves in. Midseason reappearances from Frank Lopez and Juan Galindrez up top helped the problem, but inconsistency still reigns.

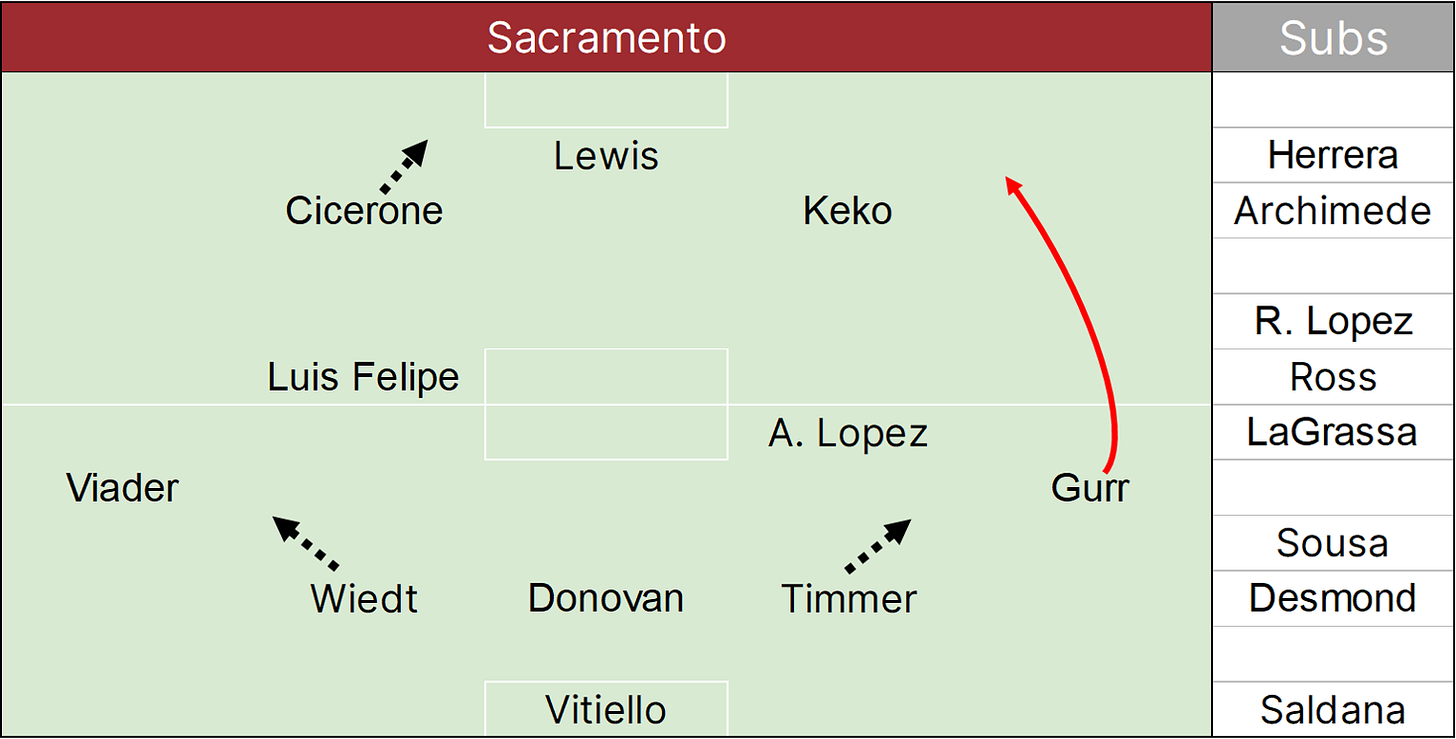

Sacramento Republic

Sacramento’s defense is stunningly organized and compact in a deep-block 5-4-1. The three-center-back line doesn’t play very high, allowing Danny Vitiello to stand on his head in goal.

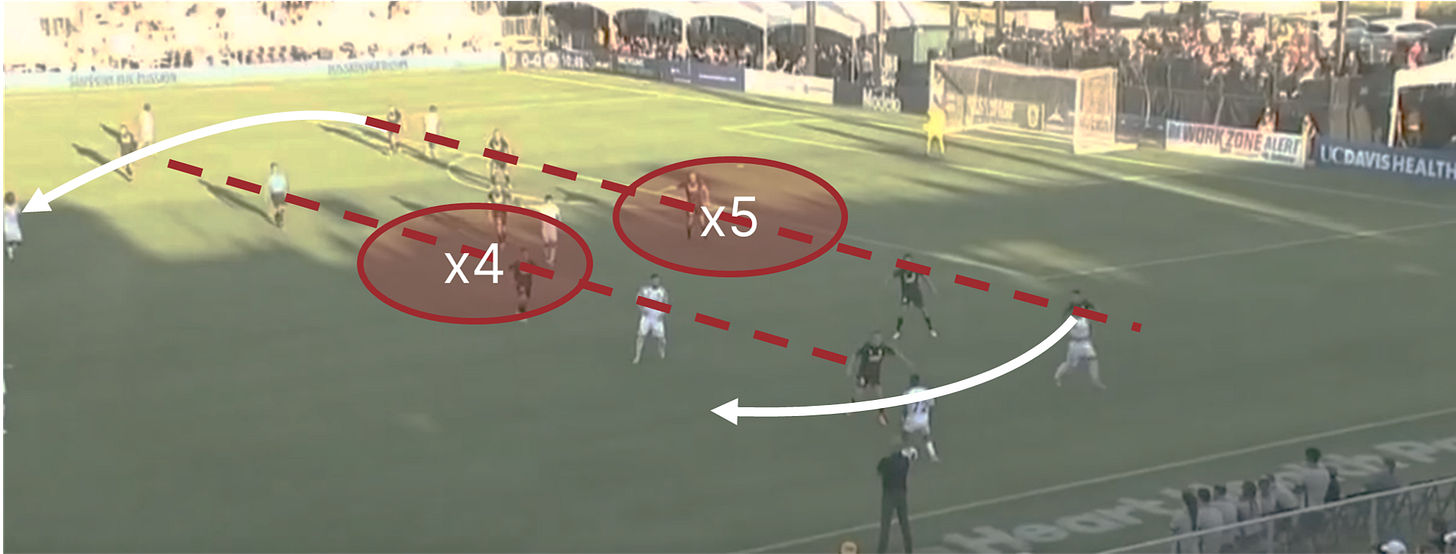

Pressing in more of a 3-4-3, the Republic can tilt their attackers towards one vertical sector of the pitch to compress upon opponents and force turnovers.

The defensive system is aided by a give-and-take pairing in the central midfield. Arnold Lopez is the preferred No. 6, and he sits very low to shield the back line and recycle possession. Luis Felipe advances high when healthy, abetting the press and providing that crucial odd-man edge in attack constantly. There are moments where pairings other than the Lopez-Felipe first-choice duo bleed space in behind.

Mark Briggs’ attack builds in progressive waves that give opponents headaches as moves develop. The wide CBs can dribble around pressure, but Lopez is there as safety if a turnover occurs. Jared Timmer and Shane Wiedt are standouts in those flanking roles.

The wing backs, especially Jack Gurr on the right, basically become forwards in their own sense and can under- or over-lap as needed. Gurr is especially effective, working off of his fellow attackers to overload opponents.

Sacramento uses no more than one proper No. 9 - Sebastian Herrera, typically, though Zeiko Lewis is a good linker there - in the final third. Herrera’s hold-up can prove fruitful, but using three straight-up attacking midfielders a la Keko, Russell Cicerone, Rodrigo Lopez, etc. encourages fluidity. The front line can effectively interchange with one another and adjust in response to the waves of advancement from the back to addle defenses.

San Antonio FC

San Antonio remains idiosyncratic in their low-possession, high-tempo back three. Pressing in a 3-4-3 or 5-1-2-2 with high wing backs and bruisingly physical forwards, the defending champs are a test for any offense in build. This is a team that fouls quite often to deny counters and break up flow.

The central midfielders in the system often split high-low with one member joining the high press and another playing centerfield in a deeper spot. More often, Alen Marcina relies on a single No. 6 behind two higher CMs. To steel up that thinner spine, San Antonio often presses their WBs or wide center backs up into the middle of the park.

Those wide CBs are crucial going both ways. The athleticism of players like Lamar Batista and Mitchell Taintor helps to cover the channels, and the precise, direct passing shown by those sorts drives the San Antonio attack. Fabien Garcia holds it all together as the staid middle man.

The forward line always includes one or two skill players best represented by Jorge Hernandez. Alongside Tani Oluwaseyi and Justin Dhillon, themselves a blend of technique and brawn, those truer No. 10s have room to break down opponents and work effectively to drive controlled transition or make headway against settled blocks.

Still, the long ball rules, and this team is best when able to generate one-on-one or two-on-two moments that lead to high recoveries. San Antonio has a remarkable ability to overload the box.

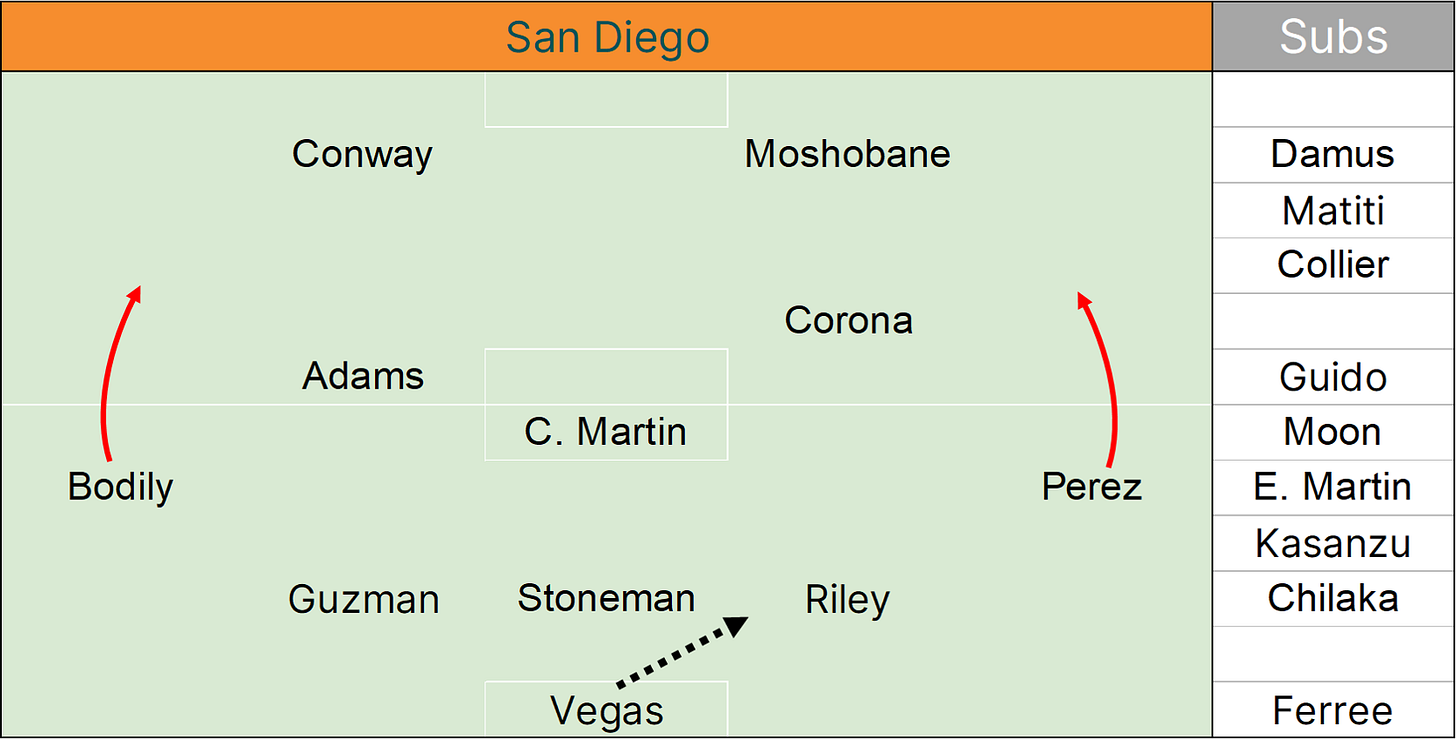

San Diego Loyal

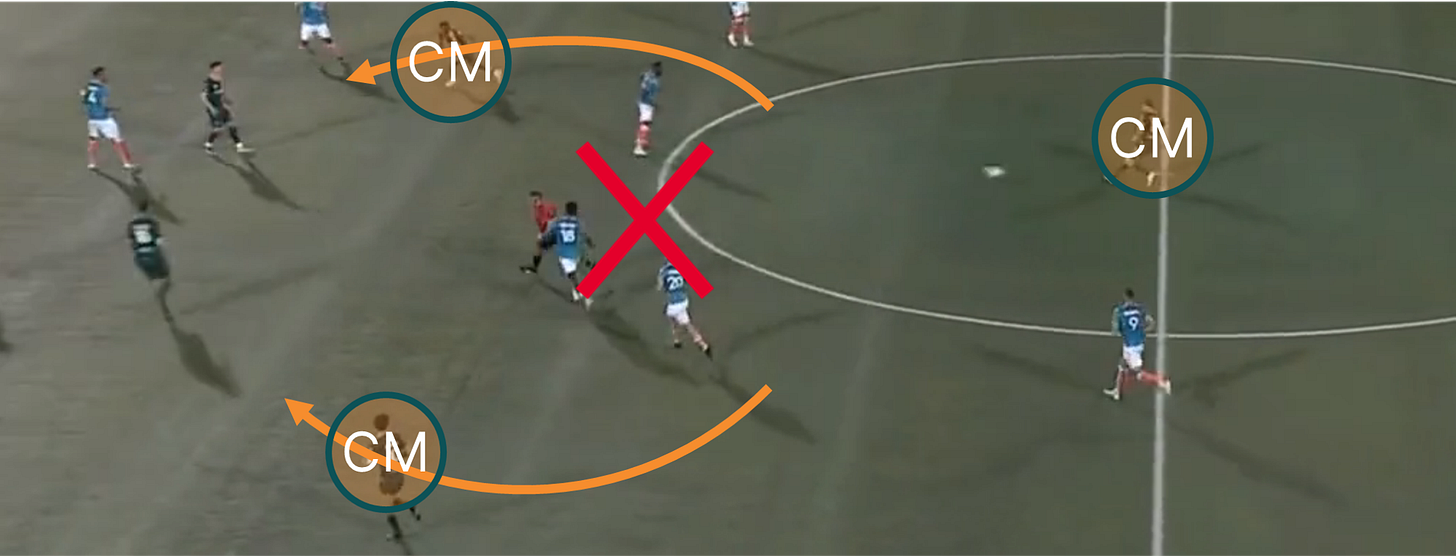

The Loyal, active in their phase-based iteration between a back three and back four in the past, have settled into a consistent 3-5-2 or 5-3-2 look in 2023. Their defensive line plays at a mid-to-high level, and their wing backs are very aggressive in supporting an expansive press.

Centrally, one midfielder holds deep as a true No. 6, allowing the two more advanced central midfielders to rove in the press. When paired with mobile forwards and advanced WBs, this alignment can clamp down in tight triangles that pin foes to the sidelines. Rarely, missteps expose that lone holder against breaks.

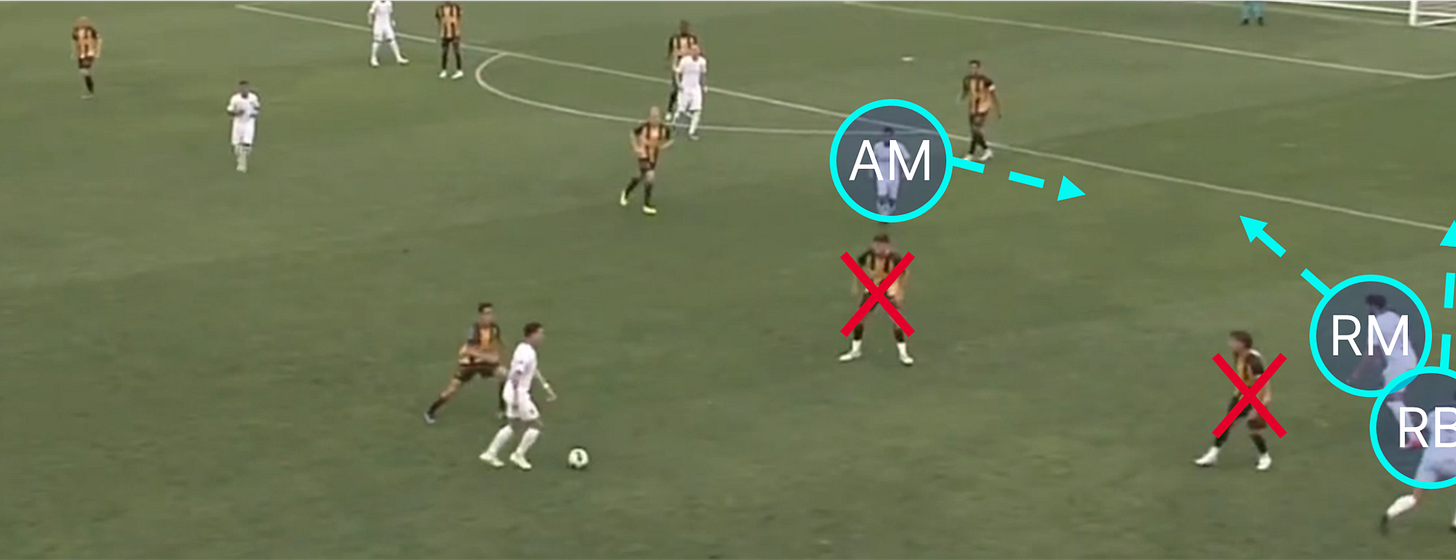

In attack, the same principles hold. Two CMs are always in the half spaces. This could be Alejandro Guido and Tumi Moshobane as proper No. 10s or Collin Martin and Charlie Adams as deeper passers, but it always gives San Diego a full range of passing angles.

Build for the Loyal starts with an always short-passing foursome composed of three center halves and goalkeeper Koke Vegas. The Spaniard steps into the spot occupied by the right CB in most teams, and he underlies the team’s overloading capabilities from the back. Call it a 4-2-5 in build.

Advances from Nick Moon before his injury, Blake Bodily, and Adrien Perez at WB stretch opponents and open the center of the pitch in the final third. Manager Nate Miller is creative in his deployments at those positions, occasionally inverting the players or varying their height to take advantage of specific opponents.

Tampa Bay Rowdies

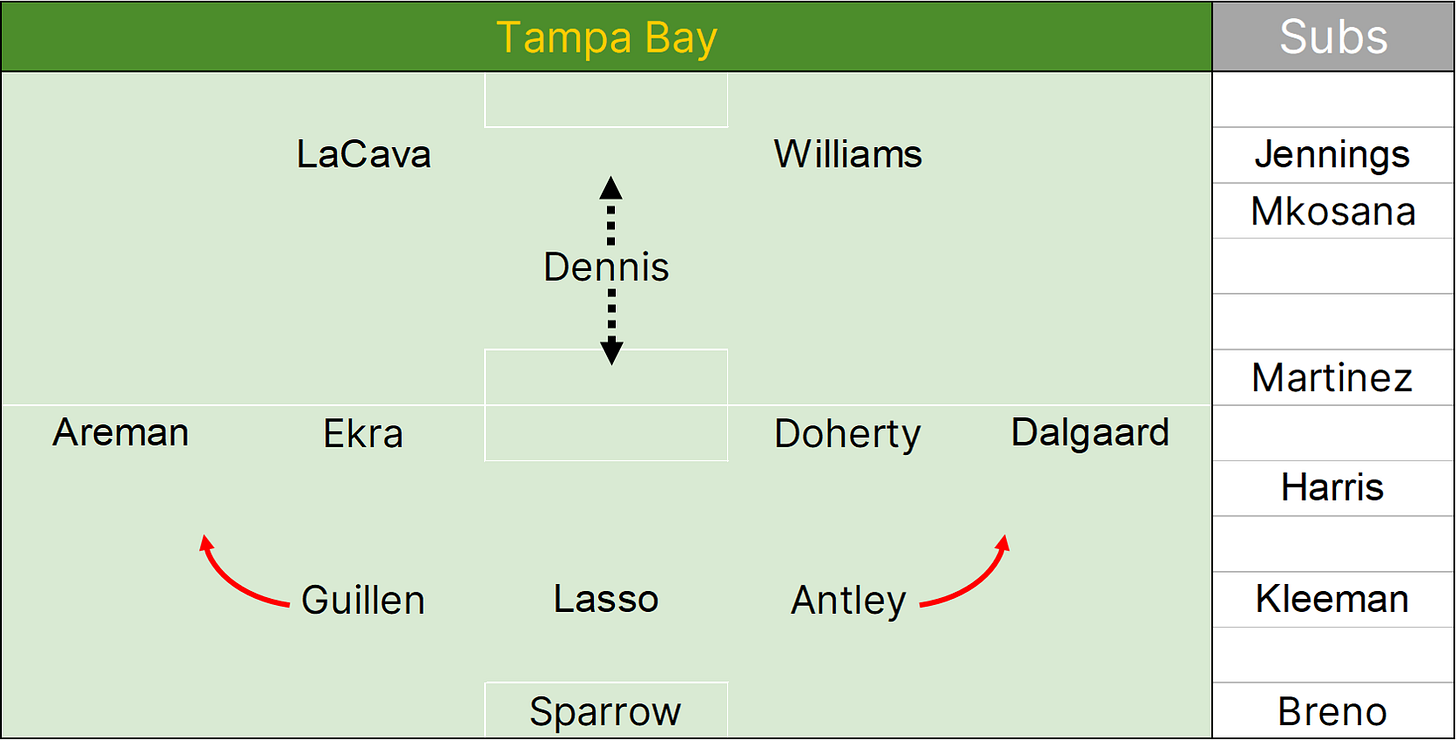

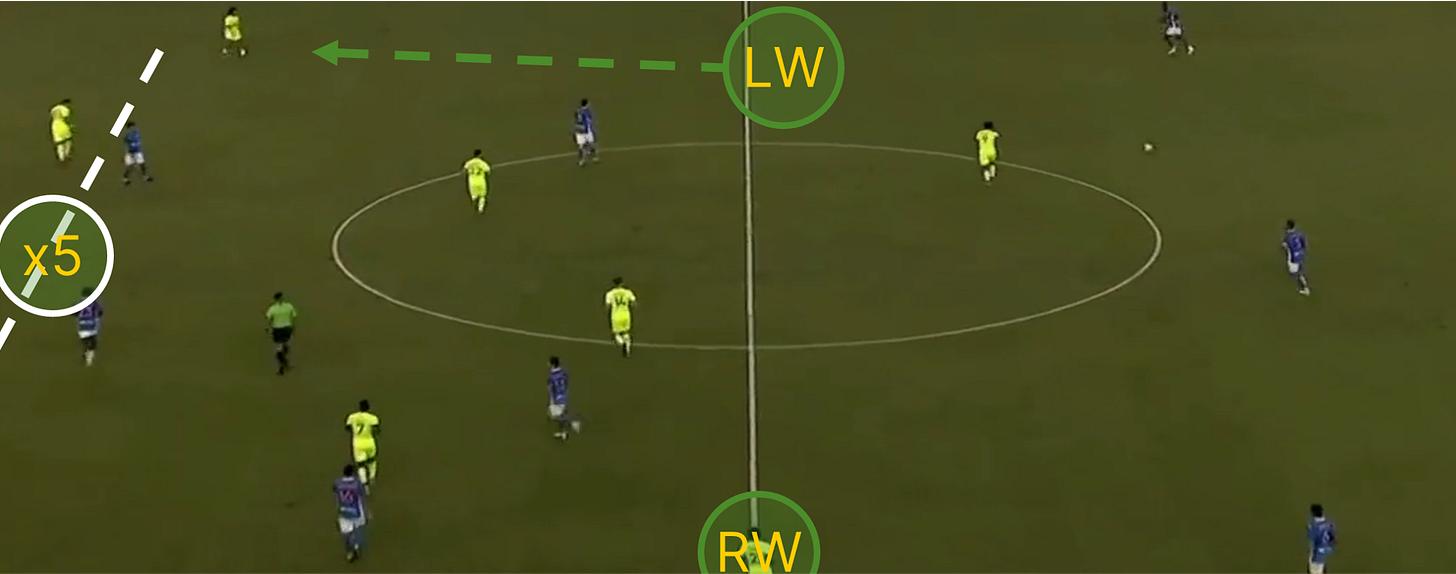

Nicky Law’s Rowdies are still a back-three side, but that base shape comes with variation. An offensive 3-4-1-2 or a similar shape can become a classic 4-4-2 in block. Either way, this team holds a medium-height line, rejects easy routes for progression, and relies on a hard-closing back unit against searching balls between the lines.

In their own third, the Rowdies can shift into more of a back five. At one point, that change was forged by Ryan Spaulding moving from the wing of a 4-2-3-1 into a proper LWB slot. More recently, the shift has been forged by Conner Antley or Jake Areman doing the same.

Tampa Bay’s wider CBs, often Aaron Guillen and Conner Antley, can slip out into the central midfield in possession, anchoring build and allowing a proper centerman to push up. Still, both are capable on the overlap and are effective because of their positional discretion.

Charlie Dennis drives offense as a free-roaming No. 10. He can drop deeper to carry the ball in build or serve as a shadow striker available for cutbacks behind the No. 9. He can also drop deeper, allowing Jordan Doherty - the most underrated player in the USL - to step up from his basic No. 6 deployment to create an overload and fool the defense.