The state of Lilley-ball

Has Pittsburgh's legendary manager done enough to keep up with an evolving USL Championship?

With a tip of the hat to my friends over at the Mon Goals podcast for chatting about the Riverhounds and stoking this line of inquiry, I want to talk about Bob Lilley.

It’s taken as a given that Lilley always has the answers; no manager in the USL is surrounded by a similar mythology. Still, in 2025 there’s a nagging sense that Lilley-ball is too inflexible for the demands of an improving league.

That’s not to say that Pittsburgh’s setup is inherently wrong, and I’d bet this team makes the playoffs. What I am saying is that the Riverhounds’ system is uniquely reliant on manufacturing certain game states. They struggle when that doesn’t happen, which is why Pittsburgh hasn’t won a game without keeping a clean sheet since July 2024.

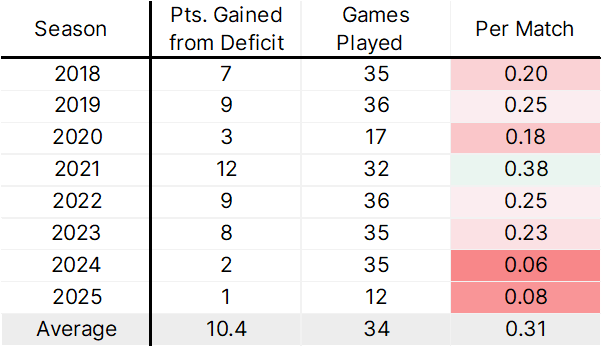

No team has earned less points from losing positions (i.e., re-gained a lead after trailing in a given match) than Pittsburgh over the last two years. The USL average is 15 points accrued in those comeback scenarios, but the ‘Hounds have picked up three across nearly 50 matches. This team hasn’t had a comeback win since 2023 against now-defunct Memphis 901!

Reversing deficits is antithetical to the Lilley model. Pittsburgh is designed to gunk up opposing pipes when the match is level. Once the Riverhounds score, defending with frustratingly perfect organization is the modus operandi. They don’t have the tools or intention to ever go all-out in attack.

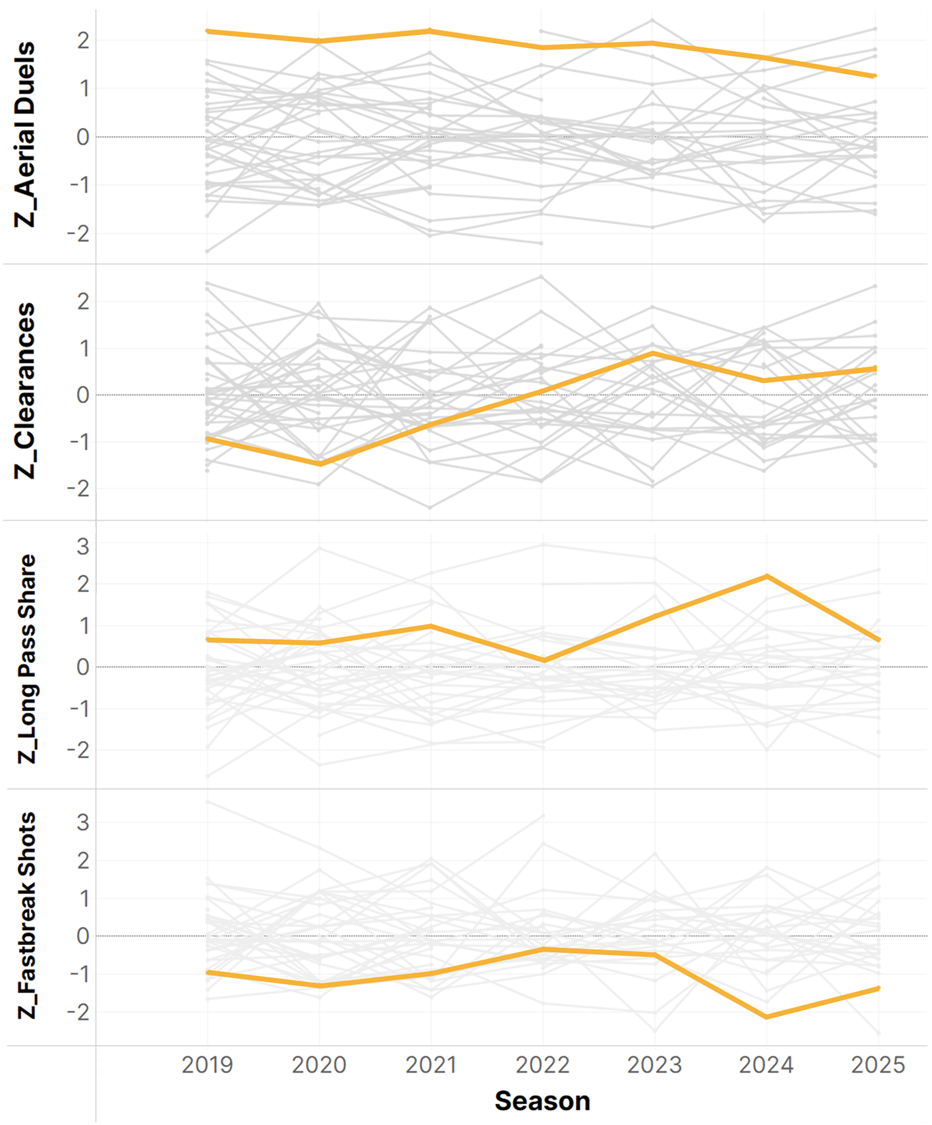

At risk of getting too nerdy, I want to examine some of Pittsburgh’s metrics from the last seven seasons, standardized against USL averages.

Each chart maps team-by-team z-scores across certain statistical categories. If Pittsburgh comes up with a value of 2.1 in terms of their long passing, it means that they hoofed the ball forward at a rate 2.1 standard deviations (i.e., 5% or so) above league average in a given season.

The data reveals a few things about the Riverhounds, who have used a 5-4-1 formation or thereabouts for the last half-decade. Lots of Lilley tenets have remained the same during that interval. This club has consistently rated as one of the premier long-passing sides in the USL. They’re also a leader in aerial duels, which is a function of that direct attacking style – and of a compact defense that forces opponents into low-percentage crosses.

Still, the numbers show that the Lilley system has lost its luster in key areas. Pittsburgh has been forced to clear the ball more often in recent seasons, meaning they’re less able to keep the ball away from their net. Fast-break shot creation has also cratered from “below average” to “problematic.”

Lilley is dogmatic in more than just his style. This season, Pittsburgh has used the second-least unique starters in the USL, just 17 distinct players. On average, the Riverhounds have used 4.1 substitutes per game, meaning that they typically leave a change on the table. Those marks are comparable to famously low-budget Loudoun United’s.

The outside consensus has long held that the ‘Hounds are working off a low budget in their own right. Why else would they sign so many college players – right?

Recent signs belie that assumption. Augustine Williams surely didn’t come cheap, nor did Bertin Jacquesson after his hot end to the 2024 season. At a certain point, Pittsburgh’s choice to rely on recent collegiates is just that: a choice.

So far this season, the Riverhounds have awarded minutes to seven players fresh out of school. No other club has reached 50% of that total. Some such players (think Beto Ydrach and Guillaume Vacter) have been stellar, but it’s a style of squad construction that’s increasingly out of line with a professionalized USL.

When rubber hits the road, all those factors – roster build, tactics, inflexibility – combine to cause trouble. Last weekend’s loss to Indy captured a bit of everything.

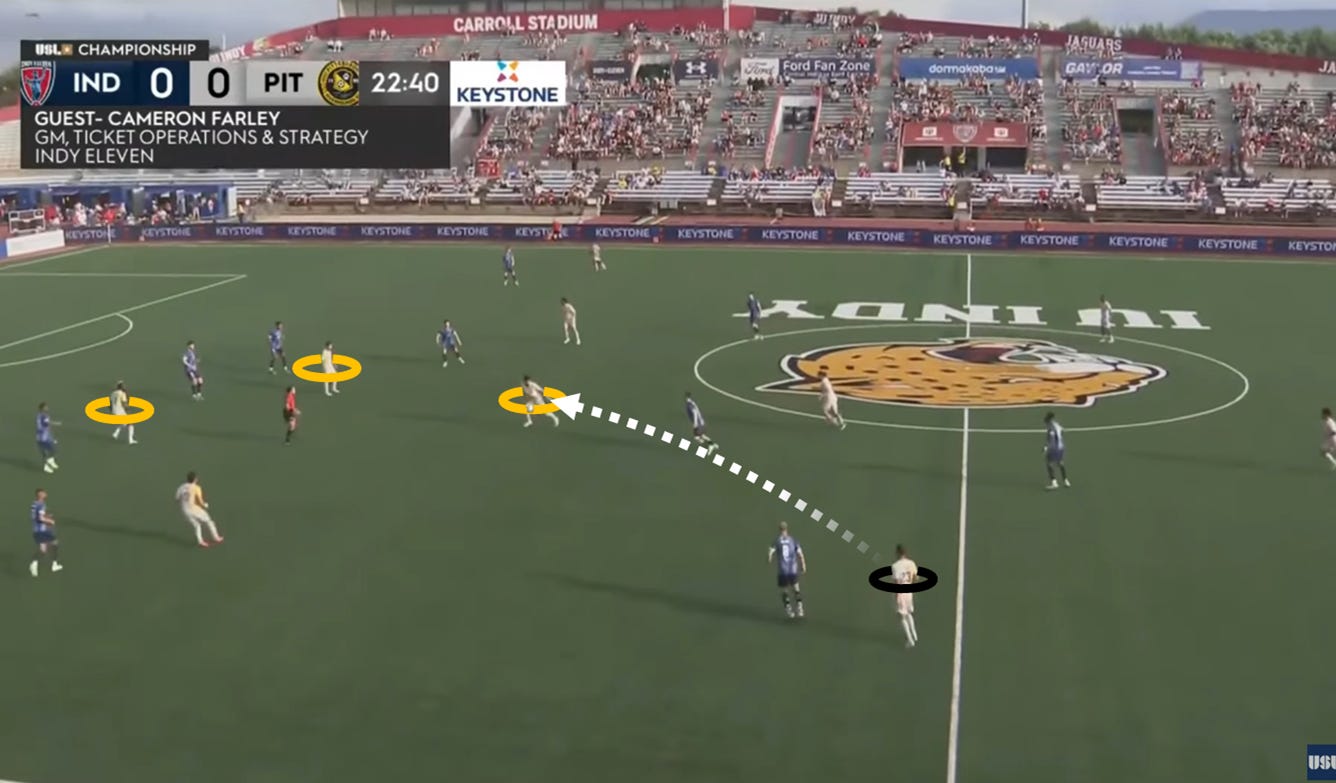

Consider this situation against the Eleven, where Robbie Mertz is receiving between the lines. The game is tied 0-0 here, and Pittsburgh has cycled the ball around the back to force Indy deep. It’s a good position for the Riverhounds on the face of things.

In a tactical sense, this is the exact scenario Lilley wants to create. Pittsburgh has systematically pushed the opponent back, and his back line can push to the halfway line to compress the field.

Still, the tilt of the pitch doesn’t really cause trouble. Williams is halfway into a turn that could take him into the box from the No. 9 spot, but who else is actually challenging? As we know, Mertz has come deep to receive. Meanwhile, fellow attacking mid Danny Griffin has his back to goal. If he receives, his 180° span of vision is entirely backwards. Thus, the defense can center in on Williams.

In actuality, Mertz bumbles on the touch you’re seeing above, and this play amounts to nothing. Still, the lessons of the shape are clear to see. No one is pushing Indy back into their box, and the Mertz/Griffin pair is serving a duplicative purpose.

Mertz and Griffin are terrific players with varied skillsets. On his day, the latter is one of the most cerebral, tempo-aware No. 6s in the league, while Mertz can do anything from the left wing to the pivot. Only 20 USL players have completed double-digit through balls since the start of last season, including. Mertz and Griffin.

Here, though, that variety melts away. Using both players as tucked-in wingers in a 3-4-2-1 forces two idiosyncratic stars into the same role – and sacrifices the possibility of adding a defense-stretching No. 9 to pair with Williams.

Heading into the year, it seemed that Jacquesson and Williams would form a duo up top. Because of an injury to Jacquesson and managerial impatience, they haven’t had a chance to build chemistry. By my reckoning, the duo has shared the pitch for less than 350 minutes so far this year.

In that time, Jacquesson and Williams have attempted only 3.7 shots per 90 minutes. That number is poor in isolation – Cal Jennings puts up identical volume as one guy – and is made poorer by the fact that none of those shots have gone in. Jacquesson hasn’t been on the pitch for a Pittsburgh goal in 2025!

Returning to the shape point, it’s worrying that Lilley isn’t adapting within matches themselves. In Indy, Pittsburgh conceded early and needed a Jacquesson-esque runner to mount a challenge in the box. As seen above, however, Pittsburgh persisted in a 3-4-2-1 (or, at worst, 3-6-1) attacking shape deep into the second half. The Riverhounds saved three of their subs for the 80th minute!

It’s a consistent theme for Pittsburgh. In another 1-0 loss against Rhode Island in the Jagermeister Cup, the Riverhounds subbed Jacquesson out for midfielder Jorge Garcia and nullified their shape at their own behest. Lilley only used three of a possible five substitutions in that match while trailing for more than 70 minutes.

It’s all a bit of a doom loop, at least when things go awry:

Pittsburgh sets up in a defensive-minded shape with little variation, so opponents know what’s coming.

Pittsburgh concedes.

Pittsburgh doesn’t make attacking-mind changes and fails to mount a comeback.

The defense, which is conceding just 1.1 xG per match, is eminently reliable. No team has a more solid floor than Lilley’s Riverhounds. I want to be very clear: that’s an incredible achievement, especially as Pittsburgh has sustained that identity for so many years. That said, the stinginess is coming at an increasingly steep cost, and 2025’s historically fecund attack has put a limit on this club’s ceiling.

Should we expect improvement? The jury is out. Pittsburgh’s 9.8% conversion rate is sixth-worst in the league, and you’d expect it to take a leap if this were any other club. However, that mark is actually above the 9.7% average this club posted between 2022 and 2024.

Expected goals don’t hint at a leap either. Pittsburgh has scored at 97% of their expected clip, which is actually a vast improvement over a 78% rate of return against expectation last season. There isn’t low-hanging statistical fruit for this team to pluck.

At the end of the day, I’m certainly not calling for a change. Lilley is a legend for a reason, and his brand of soccer has stood the test of time. Lilley-ball is designed to frustrate. Sometimes the frustration turns inwards, but that’s the trade-off which makes Pittsburgh a perennial playoff team.

In a USL defined by its shifting sands and perpetual overhaul, Bob Lilley is a bastion of dogmatic consistency – Ozymandias on the Monongahela. Do opponents still look on his club and despair? That’s the question lingering over the Pittsburgh Riverhounds, and it makes them the most fascinating organization in the Championship.

Cover Photo: Pittsburgh Riverhounds SC / Instagram