The Back Four: Switchbacks, back up?

On Kyle Vassell, Alta's downs and Knoxville's ups, the El Paso defense, and more USL miscellany

Welcome in to The Back Four!

Before we start, check out Backheeled for Rhode Island’s midfield, Hartford being excellent, and more. You can also find This League! on the site for an audiovisual dive into the week that was.

Without further ado, let’s get to it.

On Kyle Vassell

How you measure “efficiency” might seem like a question with one answer, but it’s largely dependent on your team’s system. A high-possession side like Charleston or New Mexico might look at their passing accuracy or the number of non-cross box entry passes they’ve attempted. A more direct team might look at recoveries in the middle and final thirds as a sign of success.

Colorado Springs has been chameleonic this year, but one number stood out from their win against FC Tulsa this weekend: for every 3.2 passes the Switchbacks hit into the final third, they earned a box touch. That’s the second-lowest ratio we’ve seen all year from this team, half the USL average in 2025. It’s a number evidential of the impact that Kyle Vassell had in his first Colorado Springs start.

Vassell excelled in a few ways. The Englishman took more touches in the defensive half (9) than he did in the final third (8), belying what you’d expect out of a classic striker. Those touches were absolutely not indicative of a desire to create; Vassell completed just two passes in 68 minutes but managed to draw five fouls because of his next-level hold-up abilities.

There’s always a concern that using a No. 9 in that manner might leave you bereft in the final third, but Colorado Springs split that atom by using Juan Tejada as a shadow forward underneath Vassell in their 4-2-3-1. If the former San Diego Loyal star dropped in, Tejada usually pressed ahead.

That’s not to say Vassell wasn’t bright upfield. Indeed, the moments where he rode the defense’s back shoulder – uncountable on the stat sheet – were the most impactful of all. You’re seeing one such instance here, coming in the wake of a long restart where both Vassell and Tejada challenged for possession around the center circle.

The result? Tulsa’s three center backs collapse to the Colorado Springs heavies, thereby allowing Quenzi Huerman to receive space after an ensuing knockdown goes the Switchbacks’ way. As soon as James Chambers’ side won the second-ball battle, both forwards turn upfield and go at the defense. Whether in direct scenarios like this or more grounded build sequences, the hosts used the gravity of their No. 9(s) to open space between the lines for Huerman and Jonas Fjeldberg to do their inverted thing.

Same idea here, with the play coming on the ground. Colorado Springs lets Huerman drop in to facilitate, partnering him with right back Akeem Ward and midfielder Marco Micaletto. A Tulsa center mid closes to the latter, while a wingback addresses the former. Thus, there aren’t enough numbers to address Huerman, who can make a third-man run to receive and break lines.

Beyond the fact that the tempo and movement are really solid, you might notice that there’s a gigantic gulf in the midfield. Some of that phenomenon relies upon Micaletto’s drop, but Vassell’s gravity also plays a role. Because the No. 9 is stretching over the top, a center back can’t step to intervene against Huerman.

The wonderful thing? Vassell still manages to sneak past the set defense and receive in the box. He notes that Tulsa’s centermost defender is backtracking and cuts hard against that momentum, allowing for a reception in the box. A shot ensues, encapsulating that final-third entry-to-box touch synthesis mentioned up top.

This is simply the best we’ve seen Colorado Springs look with the ball all year – and they did it against one of the USL’s best defenses. That’s a credit to Vassell, but it’s also indicative of Chambers’ ability to balance the rest of his front line to get the most out of the star forward.

El Paso’s defense

Is El Paso legit? The answer increasingly looks like a “yes,“ and that’s because of their eminently organized defense. What’s making it happen, and why did things look so bad against Phoenix?

Since the start of July, the Locomotive have had to clear the ball just once for every two ball recoveries they’ve made. In other words, El Paso is terrific at forcing bad passes and re-gaining possession long before their back line is put under pressure. During that same span, a USL-high 55% of the Locomotive’s recoveries have come in the middle third of the pitch.

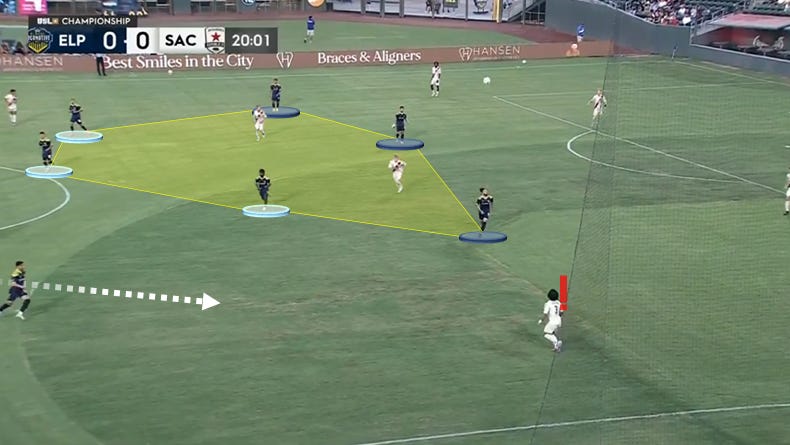

We’ll get to the moments where that model falters, but let’s start with Wilmer Cabrera’s shape. It’s easy to call the Locomotive look a 4-3-3, but the press can often look like more of a 2-3-2-3, with the fullbacks pushing ahead in alignment with the primary No. 6 to plug holes. In practice, that reactive setup looks as so…

…with right back Memo Diaz seen popping upfield from right back. This screenshot firmly falls in the “4-1-2-3” bucket if we’re being strict, but you’re seeing why opponents have struggled to break El Paso down. This team rarely gives you an inch in the central areas, and they’ve aligned their defense in a manner that allows for graceful wide rotations.

Last weekend’s win against Sacramento was a prime example of that dynamic. The Republic typically try to hinge into a 3-2-5 in attack, but they couldn’t work up the ladder and maximize their wingbacks in halfspace-centric combination play. If the Republic went the opposite way and dropped the wingbacks deep, you got situations like that in the screenshot above.

Amidst that highly organized shape, individual performances have also mattered. Ricky Ruiz and Kofi Twumasi have blossomed into the USL’s most unexpected left-side duo, anchoring the transitions between that aggressive defensive posture and what’s essentially a wonky 3-4-3 in attack.

You might expect Ruiz to push forward in such a shape – he’s a natural winger, after all – but he actually sits deep like a third central defender. That alignment lets the right back push up instead, and it frees Gabi Torres to dominate matches while transitioning from the No. 8 spot to a “kinda just combine with Amando Moreno up the left” deployment on the opposite sideline.

Meanwhile, Twumasi – little-used as in Rhode Island in 2024 – has started every match since July 4th, helping to inaugurate the defensive glow-up. He’s the stay-at-home partner next to the more aggressive Palermo Ortiz, and the duo has come together splendidly.

Ortiz ranks in the 98th percentile for long balls per match and wins 5.4 duels per match. Everything about his game is oriented forward. Twumasi puts in 33% less duels, but he’s El Paso’s leader in blocked shots and does what you’re seeing in the screenshot above: position himself impeccably to support Ortiz’s ball-pursuing tendencies.

The screenshot deserves another word. Sacramento has broken past the midfield line, and Ortiz knows it’s his job to stop the carrier. As that happens, Twumasi and Ruiz tighten up, while right back Memo Diaz is also seen making a rotation. What’s ostensibly a dangerous situation is nullified because of the clarity of responsibility at each spot across the back four.

This Saturday, we saw far less of that chemistry. The Locomotive’s rest defense struggled to maintain structure, and Ortiz had a hugely destabilizing first 10 minutes.

You see that here, where the back four is out of alignment. The big difference? Play has moved beyond Ortiz after his attempt at an intervention upfield. This moment comes after a midfield turnover, one that goaded the Juarez loanee to try and save the day upfield. The result is a seam in the back line that’ll allow Phoenix to take an early lead.

El Paso was actually quite clean at the back with the ball at their feet, writ large. The turnovers were a rarity. 95% of the Locomotive’s own-half passes were completed, the third-highest rate in any match in 2025.

Still, every slip-up felt deadly, and El Paso compounded on those struggles thanks to recurring spatial issues. Unlike in the Sacramento match, Phoenix was regularly able to break around the edges of the high 4-3-3 and activate their wingers one-on-one against Diaz and Ruiz. Those moments drew the eyes of Ortiz and Twumasi in support, creating deleterious chain reactions.

El Paso will walk away happy after storming back with three goals while up a man, but should we be worried in the macro sense? I think not. When you’re walking a tightrope of defensive aggression, you’re occasionally going to fall off. Phoenix is a uniquely bad matchup for this team because of their West-best wing dynamism. By now, we’ve seen enough of Wilmer Cabrera’s 4-3-3 and enough of Palermo Ortiz running the show to feel confident in El Paso’s longer-term vision.

Chart Break

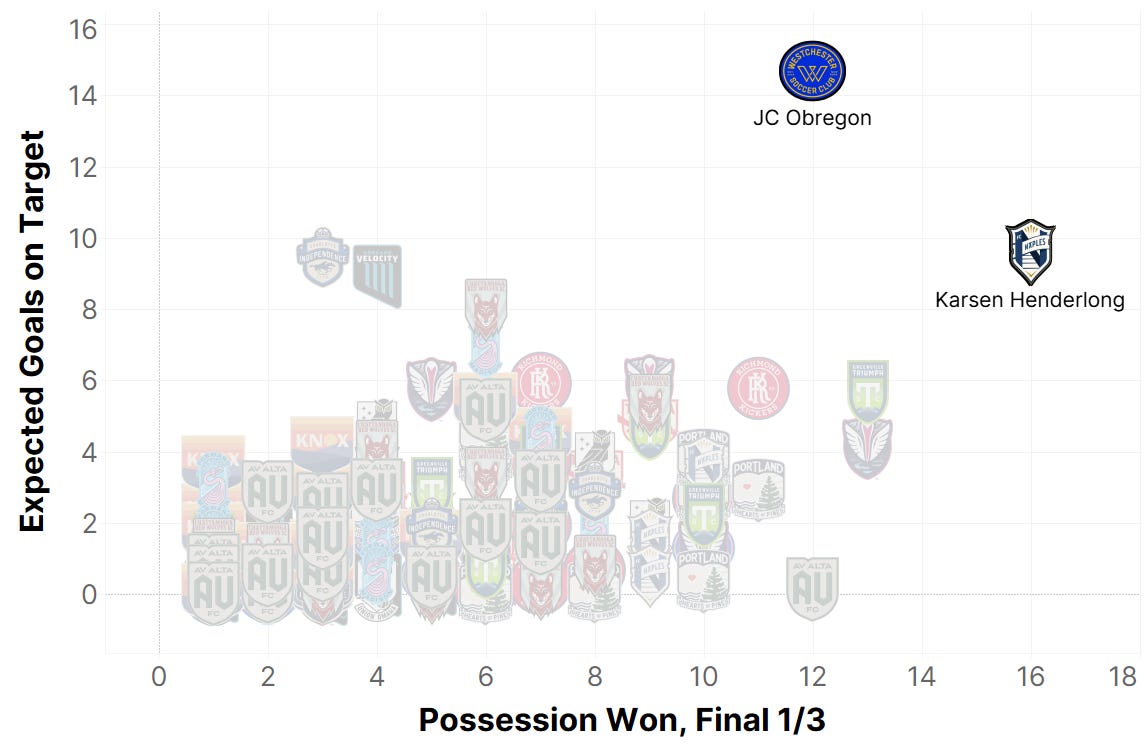

Two forwards in League One, Westchester’s JC Obregon and Naples’ Karsen Henderlong, are absolutely running the show on both sides of the ball:

Together, the No. 9s rank out as top-four players in terms of ball recoveries close to goal, and they lead the league in xG on target – essentially a measure of your shooting accuracy. If a forward has a point-blank look worth 0.5 xG, it goes down as a goose-egg by this measure if it isn’t on frame.

The moral of the story? Obregon and Henderlong are good good. As we head toward the offseason, it wouldn’t be surprising to see both get a chance to return to the USL Championship.

Anodyne Alta

USL League One has been around for seven seasons by now, and there’s never been a team more devoted to short passing than Antelope Valley. Alta’s average pass travels just 5.4 yards upfield, 10% lower than the current record-holders.

We often associate short passing and high possession with beautiful – and, implicitly, successful – soccer. That isn’t always the case. This year’s Chattanooga Red Wolves are the most direct team in League One history, and they’re doing a heck of a lot better than Alta (and most of the league, of course).

The problem for Brian Kleiban is that opposing teams have honed in on a formula to stop Alta’s preferred patterns. In their three most recent matches entering Week 26, 56% of Alta’s passes had come in their own half – up considerably on their season average. Against Union Omaha, this club played just 46 passes in the final third, their lowest count in any match since April.

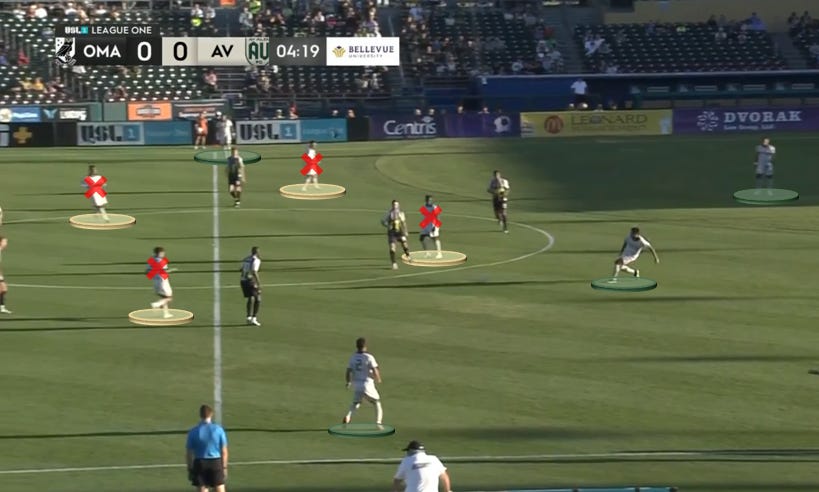

What went awry? Here, you’re seeing Antelope Valley build out in their baseline 4-2-3-1, shifting to create a boxy geometry up the middle. To do so, Alta has dropped Harrison Robledo and Eduardo Blancas out of the attacking midfield line closer to halfway.

Erick Ceja, the left-sided center back and ball-carrier in this instance, has limited options. Omaha knows that they can deny the central overload by tightening their shape; their pivot is barely out of frame, but it’s staying tight to both Blancas and Robledo. As a result, Ceja will try to skip lines and go directly toward the feet of Alexis Cerritos at the No. 9 spot.

A turnover ensues.

What if Alta tried to go wide? Same idea as above. After a center back-to-center back-to-fullback passing play, Christian Ortiz possesses at the sideline, but Omaha hinges into a 4-1-2-3 that can mark the entire midfield and pin Ortiz. There’s no way to work forward, and a back pass is the only realistic recourse.

You can chalk up the issues here to excellent defending, but Alta plays into opposing hands. This sequence is too slow; the patterns too homogenous. You rarely see this team play longer passes that might make an opposing press think twice.

I’m not here to tell you the problems when away against Chattanooga. Alta only picked up 0.37 xG, after all. Still, plays like this…

…that manipulated the Red Wolves’ 5-4-1 are something to celebrate. The standout aspect of this sequence is two-fold: there’s the (1) pace of play and (2) interchange across the attacking group.

Consider the first pass. Center back Miguel Pajaro doesn’t simply aim at the first player to his side. Instead, he drives a pass around the edge of the four-man midfield, accessing right back Christian Ortiz with room to dribble. By skipping a first-choice outlet, Alta necessarily speeds up.

Ortiz moves from there, giving-and-going with Jerry Desdunes to advance into the attacking zone before the Chattanooga midfield can recover. The fun thing? Desdunes is the starting striker. If the receiver were simply right winger Walker Martinez, there’s a good chance an opposing defender would be clamping down. This play comes amidst a bout of interchange that plants a seed of doubt in the opposing wingback, therefore allowing for the one-two.

Yes, Ortiz can’t thread the needle in zone 14 in this specific case. Yes, Antelope Valley still hasn’t won in the league since July 5th. Still, they’re picking up valuable points even while in the doldrums, and they may be figuring out how to evolve their attack.

At the end of the day, Kleiban is never going to turn Alta into a bunch of long-ball merchants. He can do what we’re seeing above: encourage more tempo and bravery while picking clever lineups that can grease the wheels of a slicker system.

Knoxville in transition

Entering this weekend, One Knox had generated more fast breaks than their opponent in nine matches across 2025. They averaged 2.3 points per game in that subset, losing just once.

When Knoxville has lost the transition battle – something that had happened six times in 2025 – that points per game tally slumped to 1.3, which would put this team firmly on the bubble. Of course, that’s not the case. Ian Fuller’s side sits on 35 points and is a prohibitive favorite to host a home playoff game because they control break situations more often than not.

(For the math majors: they’d ended up dead even in terms of transition opportunities the five other times entering this weekend, and their points per game split the difference. Go figure.)

Across League One, only AV Alta sees more transition xG going both ways in their average match. In Alta’s case, that’s because their transition defense can be suspect. Knoxville, by contrast, is above water in terms of their xG margin. They invite fastbreak moments and succeed at controlling them. What’s making it happen?

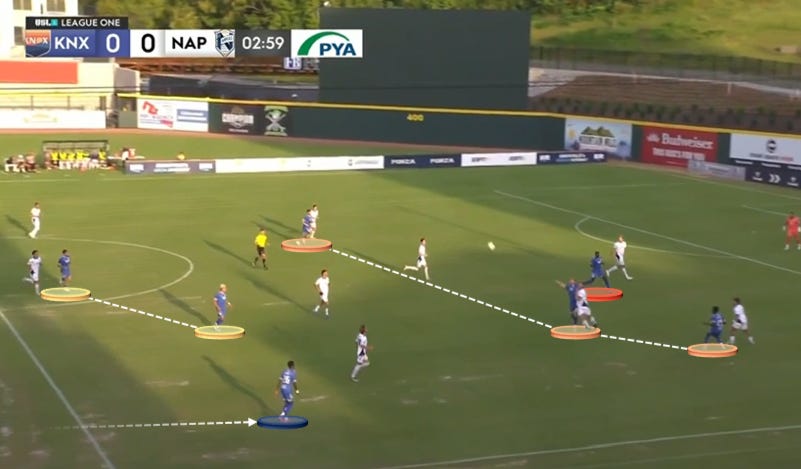

Against FC Naples at midweek – and across the 2025 season, really – Knoxville used an aggressive midfield posture and keen second-ball structure to force long balls and win them on the knockdown. Fuller’s formation gracefully blurs the line between 4-2-3-1 and 4-1-4-1, combining the upfield aggression with intelligent fullback positioning to make it all happen.

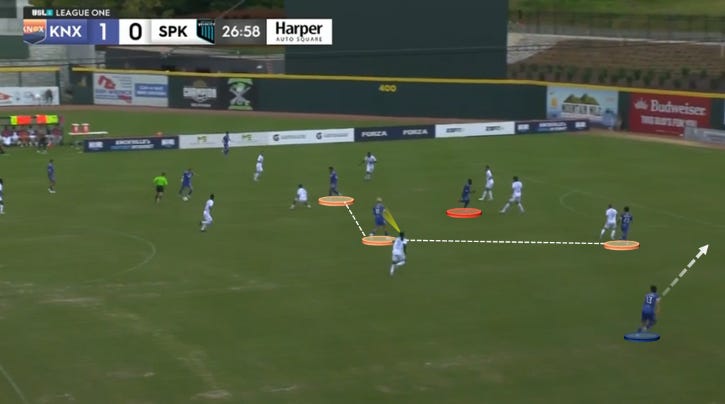

Here, the 4-2-3-1 hinges toward the right to help contest a long punt into the opposing half. Mikkel Goling is the intended receiver at the No. 10 spot, and you see Angelo Kelly (a center mid) and Jaheim Brown (the right back) hedge his way to position themselves for a recovery. If Goling manages to glance the ball upfield, striker Babacar Diene and winger Kimarni Smith are also ready to pounce.

Patterns like these are a constant. Knoxville is good about minimizing the space between their lines, using their compact vertical alignment to claim the ball. They’ve won the third-most duels per game (52.6) and are highly effective at breaking forward after regaining, as we see in the transition numbers. Players like Goling and Kelly – extremely progressive vertical runners out of the midfield – and that high-hedged fullback dynamic contribute to the excellence.

Here, left winger Nico Rosamilia loses the initial header, but the “swoosh” supporting bloc of Goling, Kelly, midfielder Abel Caputo, and left back Stuart Ritchie allows for a regain.

I’m calling it a dumb word because of the hockey-stick shape: Goling is a step upfield, but you can trace an arc through him all the way through to Ritchie at the sideline. The geometric alignment walls off a section of the pitch, limiting opposing Naples’ front line in their ability to regain.

Once Kelly gets the ball, he immediately starts to drive upfield. Doing so attracts midfield attention, giving Ritchie the half-yard of extra room he needs to beat a man up the sideline. Entering the final third, the left back can find Diene and Smith slicing in against three box defenders. A cross and Diene shot ensue.

Now, it doesn’t always go to plan. Knoxville gets bogged down when they aren’t creating short-field, transitional opportunities. Against Naples, Rosamilia and Smith struggled to involve the fullbacks on the overlap in the final third. Goling, who’s been unreal as an anchoring dueler of a No. 10, can be hesitant on the edge of the box.

There are also moments where the second-ball structure fails, and that means trouble. Naples’ best chance on Wednesday came in the 28th minute when they could round Caputo at the No. 6 spot and unsettle the alignment between Jordan Skelton and Sivert Haugli in central defense. When Haugli stepped, Brown had to tuck inside from the right back spot and fill his position. The domino effect gave Naples a halfspace lane, which they used to cross into Karsen Henderlong for a shot.

The ball stayed on the ground far more often this Saturday against Spokane, and it’s to Fuller’s credit that Knoxville came away with a statement win. The route to get there wasn’t a straight line; the Velocity used their possessive system – which regularly bends into a pseudo-back three and maximizes players like Nil Vinyals as third-man runners – to bend One Knox’s flatter 4-2-3-1 and create isolation opportunities against the wingers.

There were moments where Knoxville looked meek, allowing Spokane too much time to possess in the final third without those classic sideline traps coming to bear. The Velocity completed 119 passes in the final third as compared to 50 for their hosts. At the same time, One Knox had an ace in the hole in the form of Kempes Tekiela.

Though Tekiela’s minutes have dropped off in recent months, he’s still a rock-solid starter at the League One level. Last year, that talent mostly manifested with the German national scoring goals as a striker. This weekend, Tekiela did the job as a ball-carrying No. 10 in place of Goling.

Above, Tekiela isn’t getting a touch, but note how Spokane collapses their wings against his potential threat in the right-central pocket. Tekiela attempted four dribbles (mostly in transition) and showed a stellar sense for baiting the defense with left-footed shooting from the edge of the box. Here, those actions force the Velocity to keep immediate pressure on his back; thus, an overlapping Dani Fernandez is open up the right side.

Fernandez would later serve in the winning cross, leveraging Tekiela and Diene’s gravity to find Gio Calixtro relatively open at the far post. That moment paid off a smart strategy on Fuller’s part, one that recognized how hard it is to goad Spokane into the long game. Knoxville countered with control in this match, hence the choice to bench Goling in favor of Tekiela.

The important thing? One Knox still generated transition chances and limited those of Spokane. It all might’ve looked a little different, but that’s what Ian Fuller intended. This team can win in multiple ways, even if the break-controlling mechanism underlying it all is a constant.

Quick Hits

In other news this week…

If you aren’t reading Nicholas Murray’s Race to the Playoffs piece every week, fix your life. Clinching scenarios, tiebreakers, and the importance of various matches to the table can be hard to track even if you’re an obsessive like me, and that column makes it all easy to understand.

Related: Louisville clinched. It’s August! Incredible team.

I dove into Las Vegas’ reformed defense over at Backheeled, but I probably owe Elias Gartig a shoutout. The second-year Light hasn’t missed a minute this season. He’s blocking 1.1 shots per match (a 92nd percentile mark) and regularly throwing his body at any threat that comes his way. We’ll see how Gartig fits into the Devin Rensing project long-term, but he’s doing an immense job right now.

Tormenta! Taylor Gray at wingback! I wrote about this team in detail last weekend, but I didn’t expect them to drub Forward Madison a week later.

As mentioned on last week’s The USL Show episode, I got to see M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable followed by a Q&A with the man himself. First and foremost, that’s an awesome movie and probably my favorite of his. Second, Shyamalan is so fascinating to hear from. He’s really vulnerable about the successes and failures of his work – of which there’ve been many! – in a way that I find equally endearing and inspirational.