The Back Four: Everything’s bigger in Texas

Lone Star State catch-ups, Aodhan Quinn, Greenville, and more from the USL Championship and USL League One

Welcome in to The Back Four!

Before we start, check out Backheeled for faltering Rhode Island, New Mexico’s missing offensive piece, and more. You can also find This League! on the site for an audiovisual dive into the week that was.

Without further ado, let’s get to it.

Texas two-step

San Antonio’s victory over El Paso on Friday was a Copa Tejas duel, but it also represented a battle of Carlos Llamosa’s tactical pragmatism against a more stable Wilmer Cabrera. In many ways, this was a game of two halves – the Locomotive put up 0.07 xG in the first 45 minutes and 1.59 xG thereafter – but one that highlighted how good San Antonio can be when they’re playing on the front foot.

Out of the gates, SAFC‘s 4-2-3-1 shape had its way. Defensively, that formation flexed into a 4-2-4 and stopped El Paso from climbing the ladder up the channels or from activating the wingers at the sidelines. Amando Moreno might’ve got a rebound goal, but he and Andy Cabrera combined for just two shots on target and one successful dribble.

By pushing Nicky Hernandez up from the No. 10 spot, San Antonio created what was essentially a four-man front line that could match the opposing back four. That first wave of pressure could shift as a block while denying central angles, forcing El Paso – a team that doesn’t love going long and doesn’t have a target No. 9 – to play into traps.

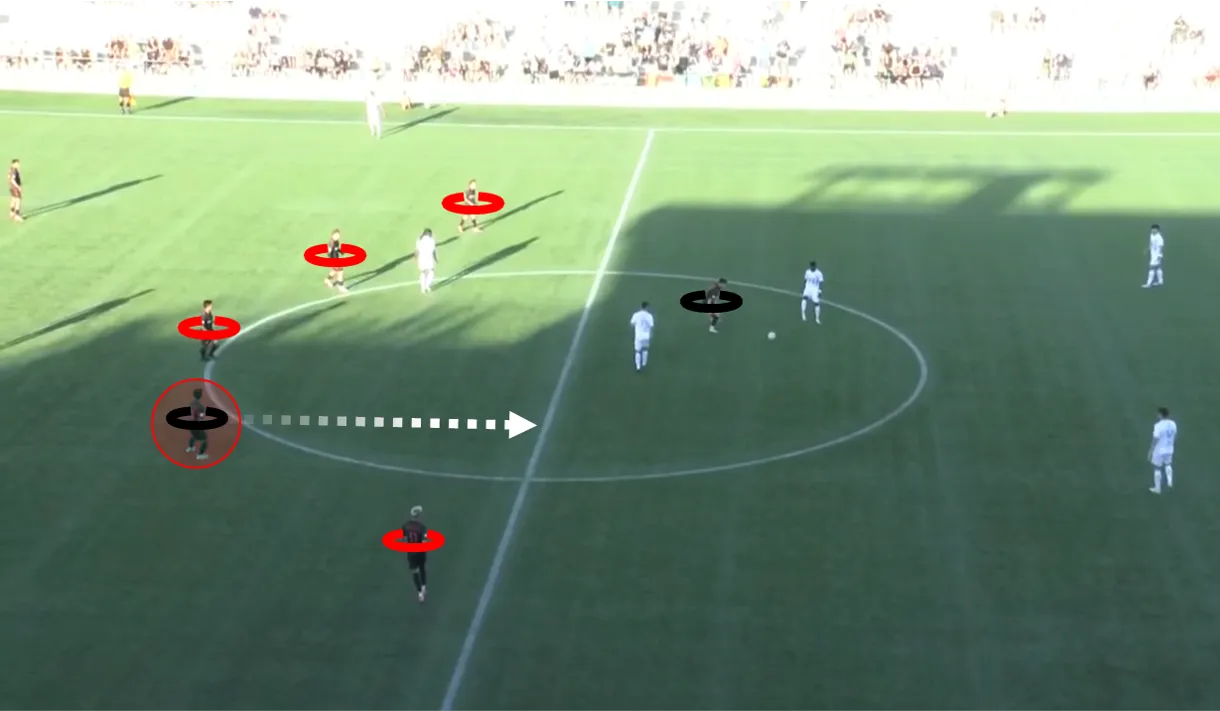

When the Locomotive pushed toward the sidelines and dropped Moreno or Cabrera deep, San Antonio reacted by allowing Rece Buckmaster and Jimmy Medranda to fly ahead from the fullback spots as markers. That’s seen above. El Paso has to work around their back end in a U-shaped pattern, and every time they crack the door ajar, a fullback is there to repel the effort.

The starting fullbacks attempted 11 duels, up from five a week prior against Union Omaha. That’s a meaningful improvement, and it captures how San Antonio sharpened their defensive approach.

This might’ve been San Antonio’s third-straight win, but it felt like a more intentional execution on a specific gameplan than we’d seen in other victories. Against Colorado Springs, admittedly with a very young starting lineup, SAFC gave up too many chances in the channels and struggled with back-three spacing. Versus Omaha in a 1-0 win, Llamosa’s side benefited from a very early goal but let Prosper Kasim have his way in the right halfspace. Notably, the inability to deny Omaha came in an ostensibly similar 4-4-2ish press.

Added sharpness this weekend forced the Locomotive to overextend and get away from the compactness that defines their best moments; a 41st minute break spearheaded by Lucio Berron against a scrambling defense was a prime example. Even San Antonio’s first goal from Juan Agudelo resulted when the high 4-2-4 press forced a risky backpass and created a turnover.

Those patterns were supported by San Antonio’s build. By keeping the fullbacks relatively low in possession and engaging them at the back, SAFC encouraged Moreno and Cabrera to get higher in the press.

It was something like a rope-a-dope: by drawing the wingers high, San Antonio could then hit longer balls toward the flanks against El Paso’s unsupported fullbacks. If those passes connected? You’re in business. If they went incomplete? You’re right back into the cycle of high 4-2-4 pressure.

El Paso improved by fighting fire with fire. Starting around the 60th minute, SAFC started to sit back, and Cabrera responded admirably by loosing his midfield. Eric Calvillo started to push up like a fourth member of the front line, and Gabi Torres did the same once he relocated from the left back spot.

At all times, El Paso had four players probing the box and rushing SAFC out of their defined sets. There was a stellar moment in the 70th minute where striker Beto Avila pressed the opposing goalkeeper into a bad pass, Calvillo intercepted, and the guests couldn’t recover their shape before a wide-open Avila found the ball about 10 yards away from goal.

The changes got the Locomotive onto the front foot. El Paso’s wingers didn’t play catch-up; they cut off passing lanes into the fullbacks before they ever opened. Pressure extended into the opposing box. The shine wore off once San Antonio counter-punched and went into more of a 5-4-1, but there’s no reason the Locomotive can’t be that bright from the first minute onward every single week.

I’ve been up and down about El Paso and San Antonio alike this year, but Friday’s duel had me feeling good on both sides. Frankly, I don’t think either team has fully settled on their perfect system, but whoever’s more willing to take risks to control the run of play will reap the reward in a Western Conference that’s there for the taking.

On Texoma’s glow-up

Entering Week 18, Spokane and Texoma had each posted 15 points in their last two months of action, and neither had lost a league match in that span. The Velocity posted a division-best 0.70 xG margin per game in the process; Texoma had been underwater, trailing by 0.35 xG on average across their unbeaten run.

Prior to this weekend’s win against Madison, the expansion side had led for just 110 minutes (a 17% share) during their unbeaten run. That’s a low number, and it improved against the ‘Mingos, but it’s still indicative of how Texoma is able to ride the wave, pester their opponents, and find moments of quality to pull out results.

Start with the stingy defensive approach. Expected numbers might not love Adrian Forbes’ side, but they’ve allowed less than one actual goal per 90 minutes since early May. That success usually comes out of a fairly low-seated 4-1-4-1, a shape that can easily become a 4-4-2 with one of the pseudo-No. 8s (think Solomon Asante or Ajmeer Spengler) and that lone No. 6 (the elite Ozzie Ramos) each pushing up a line.

Against Spokane, Texoma adapted into more of a 4-2-3-1, though you saw variation yet again. Teddy Baker started in the pivot next to Ramos but was tasked with pushing ahead whenever Spokane’s Nil Vinyals dropped for touches. Spengler was even more diverse in his positioning, picking moments to sit in a flat 4-5-1 or to chase Jack Denton all the way to the edge of the box.

Texoma presses to disrupt rhythm and create chances, but they aren’t always interested in counterpressing at the end of the possessive phase. When this team plays a longer pass in build, it typically isn’t supported by fearsome swarming. When Los Pajaros are in the final third, it’s a different story. The goal is to maintain numbers and structure no matter what, making the most of any sniff close to the net.

That approach, steady as it might be, can lead to trouble nonetheless. The Velocity got their goal by playing through the high counterpress, allowing Nil Vinyals to isolate and score. Texoma’s worst moments arise when the swarming fails and defense gets put into backfoot one-on-ones.

Still, Los Pajaros have allowed just four fast breaks since the start of May, making them the stingiest anti-transition team in the division. Dangerous counters are the exception that prove the rule. That’s a crucial calculus, given that the goalkeeping platoon of Javier Garcia and Mason McCready has allowed more than four goals above expected in 2025.

Going the other way, this team is opportunistic more than anything else. Build takes on a bait-and-switch aspect, where Texoma often starts short to draw up the press before hoofing it over the top. Their average pass has traveled 9.0 yards upfield, the third-longest in League One.

When it’s someone like Preston Kilwien hitting a pass over the top, Texoma is in business. Generally, however, this club isn’t that accurate. Their 36% long completion rate is second-from-bottom, and they’re winning just 43% of their duels. That’s indicative of a team that isn’t very effective in second-ball situations, yet Texoma is ruthless when they do come up good.

Consider the goalscoring move above. Donald Benamna is able to get a foot on the ball after a long throw, and Texoma can suddenly break with four players advancing up the right channel. Benamna, the striker, charges ahead to push the defense back, freeing Spengler to make a trailing run and put the Independence to the sword.

Texoma’s best moves come in transition when they can work in triplicate. You’ll get activity from the striker – less as an active receiver and more a physical presence that can occupy bodies. Meanwhile, a winger on the ball and a lagging Spengler will carve into that open space and go to work.

That formula, manifested with Spengler, Luke McCormick, and Brandon McManus on Saturday, gave Texoma their lead against Madison in Week 18. The same trio does the job above. Contrary to the goalscoring move, which came from considerate possession before Spengler found the ball, this one was all opportunism – the speed of thought and consistency of patterns is irresistible.

That consistency is showing up in the numbers. In their first six games, Los Pajaros put up a putrid 0.05 xG per shot and finished at a 10% conversion rate. Since then, they’ve doubled their quality above 0.10 xG per shot and upped the conversion to 17%. That’s a function of improving health, yes, but it also signifies an ability to wreak havoc and break into genuinely good positions.

That’s the formula. The advanced stats might not like it, but it’s taking Texoma into the thick of the playoff hunt. I’m not sold on the long-term sustainability, but it’s so, so fun while it’s working.

Aodhan Quinn-back

Aodhan Quinn has a claim to be the best midfielder in the history of the USL. Now at his sixth club, the 33-year-old has evolved from a safer shuttler into one of the premier offensive No. 8s this league has ever seen, and he isn’t slowing down – he’s contributing to a goal every 55 minutes in league play so far in 2025.

Quinn might be an ageless wonder, but his Indy Eleven teammates hadn’t been able to perform to the same level consistently. The Eleven began the year in a 4-2-3-1 meant to maximize wide combinations but proved vulnerable at the back. A return to a 5-4-1 added solidity, but Indy swung too far the other by deploying four ultra-narrow center mids and grinding games to a halt. Sean McAuley hadn’t found the right balance – until this weekend.

A lineup with Quinn and midfielders Jack Blake, James Murphy, and Cam Lindley allows Indy to set tempo and deny important spaces, but it can lack side-to-side movement in the final third. Indy cracked that nut against Monterey by moving Quinn to the left wingback spot and getting Maalique Foster into the lineup.

The “Foster and three proper No. 8s” approach isn’t necessarily new; we saw it in a recent loss in Tampa Bay. However, the designed imbalance and wonkiness wrought by Quinn’s deployment made the whole shape far more solid. The midfield could do its muscular thing – they allowed a season-low 0.31 xG on Saturday – and shorten the field with takeaways, but there was an added sense of verve where it counted.

Indy tilted their midfield in a few ways, using James Murphy as a higher ball-stopper in what almost seemed to be a 5-1-1-3 press. He’d step high from the pivot, while Cam Lindley held space a bit deeper. That back-end pressure supported the front three and made it difficult for Monterey’s best initiators (Carlos Guzman, Wesley Fonguck) to do their thing. Led by Foster and Blake, the attacking line stayed tight and smartly denied penetrative angles.

In that sense, Indy imposed themselves vertically by denying Monterey’s ability to climb the ladder. In a horizontal sense, the Eleven allowed Quinn and right wingback Bruno Rendon to play fundamentally different roles relative to the sideline.

Quinn took 50 touches, roughly equivalent to his season-long average. 10% of those touches resulted in crosses (a season high) that almost always were delivered from the halfspaces; he’d tuck under a roving Blake on the left wing and go to work in narrow positions, as seen during Indy’s opening goal.

Rendon, meanwhile, almost operated like another forward when Indy hit the final third. The former League One star was positively expansive on the right side, contesting 13 duels and taking 11% of his touches in the box. That relationship set the table for a “Plan A” pattern that the Eleven executed time and again: (1) force a giveaway in the high press, (2) work toward Blake and Quinn in the left pocket, and (3) serve toward Rendon against the momentum of the defense.

You see that model sequence play out above. Blake recovers a ball on the edge of the box and immediately looks toward Quinn. By the time the recovery occurs, Rendon is already a few feet outside of the 18-yard area and is looking to charge toward goal.

As Quinn gets his first touch, Monterey scrambles toward Indy’s left, and they’re forced to commit more numbers that way because Foster is also making a clever off-ball run in that direction. Meanwhile, Rendon is doing his thing and Blake is also joining the fun, having followed up his wide pass with a straight-line charge into the box.

The result? A cross from Quinn, a header from Rendon, and a play that very nearly puts the Eleven up 2-0.

Your worry was that Indy would’ve struggled in transition with Quinn out wide, but that wasn’t the case. The Eleven conceded just one fast break and allowed less crosses (13) than their average (13.2) across the entire year. McAuley’s pressing structure was designed to keep danger away from the defensive zone, and Indy put in 31% less clearances than usual because they were so good at executing on that blueprint.

Monterey is in a mini-crisis in their own right, and you’d imagine that playing Aodhan Quinn out wide might be less tenable against Eastern rivals like North Carolina or Charleston with star playmakers on their right sides. Still, this was the closest we’ve been to a fully-actualized Indy Eleven, and Sean McAuley deserves massive credit for the brave changes that made it happen.

Westchester, Greenville, and structure

Greenville is in a purple patch. Westchester, after a seeming rebound, is falling back into their bad habits. Wednesday’s decisive 3-0 win for the Triumph – with yours truly in attendance! – put the spotlight on how Rick Wright’s side has grown sharper and how their expansion rivals can’t seem to find their footing.

The Triumph re-oriented their lineup a few weeks back in a resounding win against Chattanooga, and the changes have stuck. There, Greenville grouped winger Connor Evans in the central midfield with Chapa Herrera and Evan Lee to pound a very good Red Wolves team. Lee was relatively staid in that match but showed more verve versus Miami a week later; Herrera sat deeper against the Championship side, using his creative presence to draw the opposing midfield up in the press.

All the while, Evans has been fantastically creative as a No. 8, and that held true in Westchester. There, the rookie winger-turned-center mid sat deeper in the pivot of a 4-2-3-1. That shape allowed Greenville to use Herrera as a man marker against Westchester’s single pivot, and it gave Dave Carton’s side fits.

The New Yorkers struggled with their build and rest defense structures in the 4-1-4-1. Whenever Westchester erred, their guests used vertical movement from the wings and an unflinching progressiveness to take full advantage. This was a game that made one thing clear: Westchester simply isn’t set up to stop opposing transitions.

You get a motivating example here, in a frame that comes an instant after a turnover. Already, Herrera has the ball at the No. 10 spot, while both Ben Zakowski (the left winger) and Rodrigo Robles (right) streak ahead into open seams.

This is a scenario Westchester fans will be familiar with, but what makes it happen?

The expansion side dogmatically builds out with one defensive midfielder low, creating something like a 2-3-2-3 in possession. That can vary at times, but it’s Carton’s primary aim. Given that Greenville shifted shapes into a 4-2-3-1, they had the central personnel to constantly frustrate Westchester’s second and third levels in order to create turnovers. Think about the matchups – you’ve got Zakowski, Herrera, and Robles cutting off the lower line of three, with Leo Castro wrecking shop against the Westchester center backs from Greenville’s No. 9 spot.

That’s what happens above, and it leads to a disorganized transition recovery in which a lot of things go wrong. Right back Noah Powder is too narrow. Support from midfielders Dean Guezen and Daniel Bouman to cover Joel Johnson as the lone No. 6 (looped in blue above) isn’t forthcoming. The spacing is all wrong.

This was the story of the match, which was 3-0 in favor of Greenville and all but decided before halftime. It was a major setback for Westchester, one that came hot off the heels of two strong defensive showings against Pittsburgh and Madison.

In some sense, this was a match-up problem more than anything else. Neither of WSC’s prior two foes were bold or expansive transition teams, and that let the defensive (and/or build-up) mistakes off the hook. Westchester is actually quite good when they can keep play in front of them against sides that work more slowly in open play. Pittsburgh, for instance, tends to restart long but keeps the ball on the ground after winning knockdowns. Madison only went long on 12% of their passes when they played Westchester and didn’t generate a single fast break – a shortcoming that arose from Matt Glaeser’s decision-making more than any tactical aspect of the WSC defense.

In that sense, Greenville deserve their flowers. The “Evans central” 4-2-3-1 of the last few weeks has been as malleable as it’s been effective, and last Wednesday’s adjustments were a lovely example.

This play, broken into two clips, spotlights everything I’m loving about the Triumph these days.

Initially, Greenville is seen turning the ball over at the back as they try an entry pass into a back-to-goal Herrera, but their structure doesn’t waver. Toby Sims closes from right back to stop an advance up the wing, while Evans and Lee hold firm in the double pivot. On the weak side, Zakowski collapses inside to further tighten Westchester’s angles.

WSC gives the ball away, and play quick transitions upfield just as Greenville want. We’ll get to the consequences of that field-tilting in a second, but compare the post-turnover responses. As soon as the Triumph regain, they’re looking upfield. When Westchester got the ball at the start of the clip, their spacing was nonexistent – four attackers occupied the same areas, and Greenville could easily collapse into the counterpress.

Back to the play, where Westchester has little sense of control and rushes into a clearance that’s quickly headed back their way. The Triumph use that header to advance in a wave, getting Lee, Robles, Evans, and Castro into a tight space with Zakowski lurking on the weak side.

With left back Josh Drack and elevated center back Andrew Jean-Baptiste lollygagging, Greenville forces a turnover and breaks into a two-on-one. The result is a Zakowski shot that should be a goal, capping off a sequence that encapsulates the best of Greenville and the all-too-familiar worst of Westchester.

For now, Carton’s side is far too mistake-prone at the back. Their fullbacks are constantly out of position and caught sleeping on breaks. The use of the single pivot is limiting in build, contributing to a major turnover problem. It’s notable how much better this team looks when Dean Guezen sits low next to a No. 6; his presence as a passer is steadying in isolation, but Guezen is a premium passer to boot. When he’s deep, it draws the second line of opposing pressure, allowing players like Prince Saydee (four shots on Wednesday) to get one-on-one or JC Obregon (51 touches) to hold play up.

By contrast, the Triumph have found their balance. Zane Bubb, Brandon Fricke, and the excellent Gunther Rankenburg are doing their thing at the core of the defense. The midfield structure has been resplendent. It’s been an up-and-down road to this point, but Greenville looks like a genuine contender in a way that their expansion rivals feel far, far away from.

Quick Hits

In other news this week…

The July 4th holiday is fun and all, but it’s so busy if you’re a sicko who’s self-assigned the responsibility to cover the whole USL.

I wrote about Xavier Zengue a bit in my Backheeled column, but I’m smitten with everything he and Lexington are doing. Zengue is getting almost four touches in the box per game, and the rotations behind him from Joe Hafferty and Sofiane Djeffal are basically flawless. Throw in Alfredo Midence’s verve as a tucked-in No. 10, and you’ve basically got the best right side in the USL.

Tyler Pasher is a transitional player for me, someone that I absolutely adored during the peak of my post-NASL Indy Eleven fandom. Journalistic remove means I’ll probably never rekindle that feeling, but I love seeing Pasher do the business again. He tried 11 long balls(!) against Rhode Island, combined for six dribble attempts against RIFC and Charleston, and feels fully actualized in Birmingham’s 3-4-3.

The Worst Person in the World is maybe the best “millennial coming-of-age” movie, and the follow-up from director Joachim Trier due for this November (Sentimental Value, starring Elle Fanning and Stellan Skarsgard) is maybe my most anticipated release for the rest of the year. Related: the fact that Elle Fanning is doing a talky Scandinavian drama and a Predator sequel this year rocks.