The Charleston Battery are, potentially, in the midst of a historic season. This team hasn’t lost in the league since March 29th. They’ve put up a plus-14 goal difference during that same stretch, and they’re currently posting the second-best per-game xG margin of all time with a plus-0.92 mark. It’s conceivable that Charleston might extend their seven-match winning streak into July or even August.

During each of Ben Pirmann’s seasons in the Lowcountry, the Battery have improved their underlying expected goal numbers, but this level of success wasn’t guaranteed.

Charleston lost Nick Markanich after the reigning MVP completed a transfer move to Europe. His ostensible replacements (think Johnny Klein, Douglas Martinez, and even Rubio Rubin) have struggled to even earn starting minutes. The Battery also signed proven stars like Cal Jennings and Houssou Landry, but those players entered at already-crowded position groups.

It’s required finesse to make it all click. The fact that the Battery have dominated the USL so far owes to one factor above all: Pirmann’s ability to implement tactical principles and adapt them to the talent at hand.

These days, Charleston riffs on a 4-4-2 shape with Jennings and MD Myers up top, Juan David Torres and Arturo Rodriguez inverted on the wings, and players like Houssou, Langston Blackstock, and Nathan DosSantos anchoring a back line that’s been afflicted by numerous injuries. In the middle, Aaron Molloy and Chris Allan have reprised their league-best pivot pairing.

As the Battery build out, they typically drop an extra player between the center backs to support short-from-the-back possession. That can be Molloy, splitting between central defenders and operating like a quarterback; there’s a reason he’s taking 90.8 touches per game, after all. Blackstock, who played as a wingback last season in Pittsburgh, can also do the job from the right.

When the right-sided defender sits low, Juan David Torres almost occupies a “free wingback” role up that flank. The goal is to maximize space in which Torres can roam, allowing him to isolate against defenders and pick up a head of steam.

Torres, for my money, is the most dominant player in the USL, whether he’s deployed in that manner or as a traditional inverted winger. The Colombian creator has four goals and five assists already, generating 23 key passes and 47 shots in total. He also makes 5.4 recoveries per game, evidential of his ability to influence play in chaotic, transitional moments.

It’s noteworthy that Charleston has been immensely steady in that star-maximizing arrangement despite losing center backs Graham Smith and Leland Archer for long stretches of time. Smith (the reigning Defender of the Year) and Archer (Charleston’s longest-tenured player) are as elite as they come in the USL and innately understand the Pirmann system. Still, they haven’t been missed when rubber hits the road.

Charleston’s press often adopts a hexagonal 4-2-2-2 look, with the forwards, wingers, and center mids moving as a unit from side to side, leveraging that shapeliness to deny penetration up the middle. The setup works no matter the opposing formation; Jennings and Myers can go mano a mano against opposing center back pairs, while ball-side wing support and ensuing rotation from the pivot covers up against back threes.

Optimally, the setup will encourage longer and riskier passes that the back line can deftly handle. The Battery have generated a 76% completion rate against (i.e., opponents struggle to connect passes against them) to place seventh in the league to date. Still, there’s a reason Charleston is one of just two clubs to put up more than 19 midfield takeaways and 3.5 pressing recoveries per match: they excel at imposing themselves in more elevated areas. You’re getting all the benefits of a more passive shape with the upside of an elite press.

It’s a feat that Charleston is so good at manipulating their own formation while denying that ability to opponents. Still, what does that look like in practice?

Here, an offensive move begins to gestate with Molloy (in black) having dropped deep between Michael Edwards and Joey Akpunonu in defense. Charleston’s tendency to build with a virtual back three couldn’t be clearer.

That first frame sees one opposing presser shadowing Molloy, who can easily dispense with the ball within the pseudo-back three and activate Edwards toward the left side. Edwards, for reference, is looped in yellow and is seen carrying the ball upfield between the two screenshots.

Meanwhile, Allan (also in black) puts on a masterclass in static positioning one line ahead. Knowing that the Battery need a central presence to pin opposing San Antonio, the Englishman holds firm and forces the opposing center mids to sit in. Think about SAFC’s No. 10 here, for instance: he can chase Edwards and thereby allow for an easy pass into Allan in the center circle, or he can allow Edwards to dribble ahead. There aren’t easy answers.

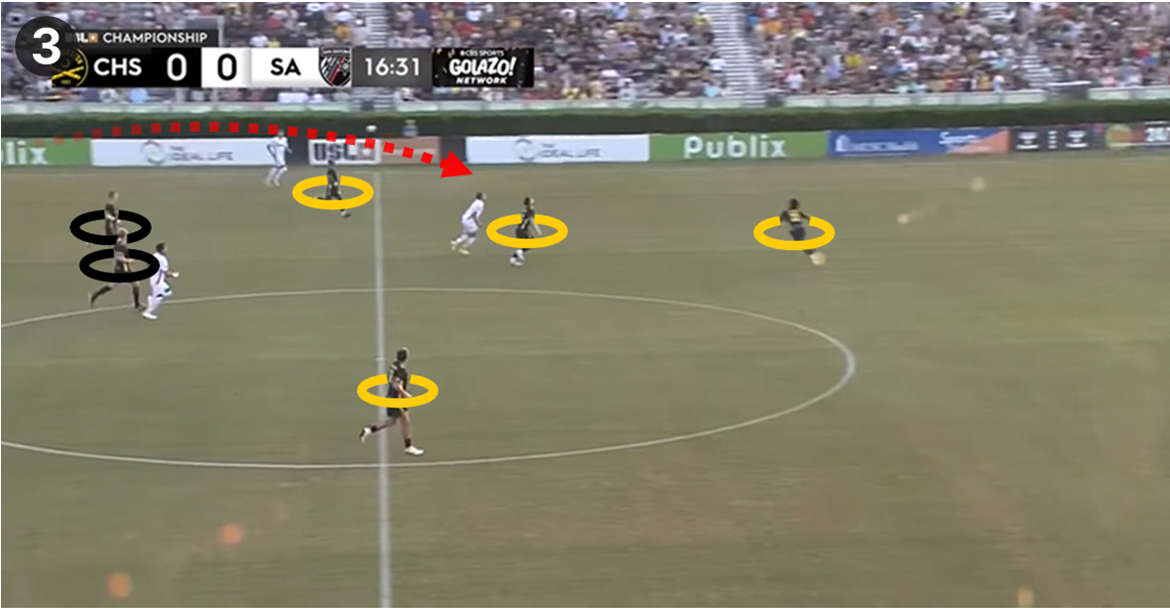

By the time Edwards hits the halfway line, alarm bells have started to go off on the opposing side. San Antonio collapses the lion’s share of their midfield toward the ball-carrying defender, and Charleston is starting to take advantage.

Edwards now has options. Myers (looped in yellow like the rest of the quasi front four) has cleverly shown low to pin the back line. Cal Jennings is beginning a diagonal run from the left halfspace between two defenders; that move will present the possibility of a through ball while also opening up the flank. Meanwhile, Torres is in a one-on-one toward the right.

The defender ultimately hits a sweeping pass Torres’ way, and it’s into the final third from there. For the record, this was a match in which the star winger took seven shots and created two chances. This pattern was used to activate Torres again and again.

Backing up a step, what principles are we seeing here? There’s so much to like between the staggered alignment of the center mids, the highly complex movement of the front line, and the way in which a defender like Edwards is emboldened to push ahead.

Still, this play will ultimately end in a turnover. Flash forward 15 seconds, however…

…and Charleston is set up to regain again. This isn’t the clearest image, but the 4-2-2-2 counterpress has forced San Antonio to lump a long ball toward an isolated forward. By this time, Edwards has recovered into position and is actually the deepest defender; Akpunonu has attacked the ball moments before this frame, knocking it into the path of his partner.

The overarching structure is equally admirable. The fullbacks are in position, and both Allan and Molloy are recovering to contest any manner of knockdown. This is genuinely faultless stuff.

If you’re to compare this year’s version of Charleston to last year’s, the change in offensive emphasis is the big growth point. Yeah, the adoption of a truer two-forward press versus Pirmann’s prior 4-2-3-1 is notable, but you’ll often see Jennings and Myers stack high-low anyway. Offensively, however, it’s the transition between Torres (a player that constantly takes up very deep positions and builds a head of steam from there) and Markanich (who camped much, much closer to the box) that’s so revolutionary. This season, Torres is taking 78 touches per game as compared to the 48 that the reigning Golden Boot winner took in the average 90 minutes.

Because Torres and Aaron Molloy demand hard close-downs and constant attention at multiple levels, defenses can’t just sit low and hope for the best. It’s nearly impossible not to overextend when you’re playing against the Battery. Cal Jennings, who led the USL with four fastbreak goals and placed second with 3.98 fastbreak xG last season, is built to dominate through the channels against defenses that can’t pack in against him.

As it stands, Jennings is in elite company. He’s one of four players in the history of the league to put up at least one expected goal contribution per game. The leaderboard is as follows:

Cal Jennings, 2025 (CHS) – 1.22 xG+xA per 90 minutes

Foster Langsdorf, 2020 (RNO) – 1.18 xG+xA per 90 minutes

Solomon Asante, 2019 (PHX) – 1.03 xG+xA per 90 minutes

Andy Craven, 2017 (OKC/CIN) – 1.02 xG+xA per 90 minutes

Rule of thumb: any time you’re in the same conversation as peak Solomon Asante, you’re probably doing something spectacular.

Amidst it all, the deployment of Houssou Landry might just be the most impressive thing Pirmann has accomplished this year. We knew that Torres could go on rapturous tears, and we knew that Jennings was the best No. 9 in the league. We didn’t know that the former Loudoun and New Mexico defensive mid could shine in the wide areas.

Shifted to fullback after a few up-and-down matches in the middle, Houssou has already shown an ability to overlap and do the job as a traditional wide threat. He’s won two-thirds of his tackle attempts so far and has been dribbled past only five times despite coming up against leading on-ball threats on a weekly basis.

Above, though, you see Houssou thread the needle of his career arc. In this case, Pirmann allows the Ivorian to tuck inside as that extra central man, remaining there as Charleston patiently circulate possession against a hard-nosed Detroit press. With their star winter addition anchoring play in the central areas despite playing as the right back, it’s only a matter of time for a defensive mistake to arrive.

Eventually, it does. Torres (playing on the left here) receives a line-breaking pass from the back on the turn and finds himself in acres of space. He looks upfield, hits Myers on the edge of zone 14, and allows the former MLS Next Pro Golden Boot winner to first-time Jennings in for a goal. It’s a tremendous example of the attacking line’s efficiency, but it’s only possible because of Houssou’s comfort at varying his positioning.

This move is a stellar example of why Charleston is so impossible to stop. Combining individual expression with principled team-wide organization is incredibly difficult to do, especially at the USL level. Ben Pirmann makes it look easy. Whether or not the Battery extend their winning streak to historic lengths, they’re the definitive favorite to win the Players’ Shield because of their holistic model, a system that’s thoughtful and ruthless in equal measure.