Devin Rensing and the USL’s Coaching Trees

On Las Vegas' new manager and what managerial lineage does and doesn't mean

After more than a decade of college coaching experience and five years spent under Ben Pirmann’s wing in the USL, Devin Rensing is the new head coach of the Las Vegas Lights. It’s a move that sets the Lights organization back on track after a faltering start to 2025, and it also hints at crystallizing patterns within the league’s coaching market.

What changes might Rensing bring to bear, and how does it fit into a flowering environment of intra-league “coaching tree” culture? Let’s dig in.

Rensing in Las Vegas

The Lights were the surprise story of 2024 in the Championship, overcoming years of failure to become a contender under new owner Jose Bautista and new manager Dennis Sanchez. When Sanchez decamped for New Mexico in the offseason, the club hired Antonio Nocerino – someone diametrically opposed to Sanchez in terms of style, fresh off a historically unsuccessful season with Miami FC.

By June, the club parted ways with Nocerino and embarked upon a soft roster reset. Star midfielder Valentin Noel and his expiring contract were dealt, as was Jamaican international center back Maliek Howell. Those moves cleared the board for Rensing, who inherits a last-place team with the USL’s worst goal difference (-21), albeit one that’s just four points off the playoff cut line in the West.

Rensing, meanwhile, has a vast array of experience. In the college ranks, he picked up trophies as the head coach at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey and served as an assistant coach at Northwestern and Colgate. Rensing first came to the USL as part of Memphis 901’s staff in 2021. Since then, he’s faithfully served as a part of Pirmann’s staff in both Memphis and Charleston.

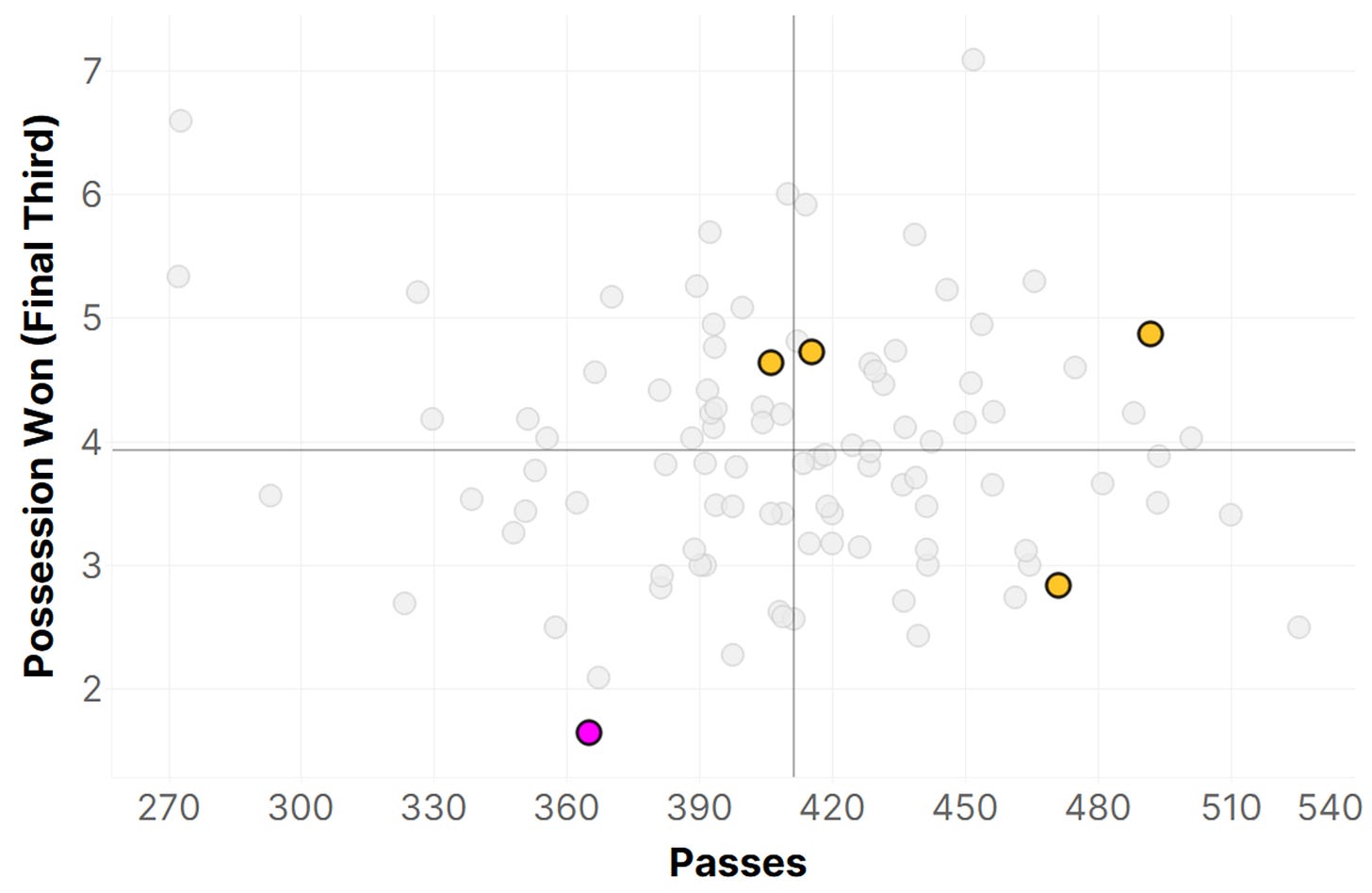

The big question: how will Rensing play? Over the last four seasons, Pirmann-Rensing clubs (marked in yellow above) have tended to be possessive and fast-paced. High pressure within a familiar 4-2-3-1 formation has been a constant. By contrast, this year’s iteration of the Lights (in pink) has been neither of those things. Post-Nocerino Las Vegas is a back-three side that defaults to the long ball and is content to sink into a mid-low block.

It’s useful to contextualize the Noel move within that setting. In the rope-a-dope, “build short to draw pressure and then go long” attacking system we’ve seen in 2025, Noel was clearly miscast. At the same time, he’s more of a box-oriented mover that isn’t necessarily an archetypal fit in a Pirmann-Rensing system. Consider a comparison of Noel against their recent No. 10s:

Kissiedou, 2022: -0.17 vertical yards per pass, 8.5% box touch share

Rodriguez, 2023-2024: 3.44 vertical yards per pass, 6.2% box touch share

Ycaza, 2024-2025: 3.10 vertical yards per pass, 8.2% box touch share

Noel, 2024: 0.66 vertical yards per pass, 12.8% box touch share

Valentin Noel is a wonderful midfielder, but he’s cut from a different cloth than a drop-and-facilitate player like an Emilio Ycaza. Noel is more similar to (and inarguably more efficient than) Laurent Kissiedou, but the Pirmann-Rensing brain trust got away from the style in which Kissiedou flourished once they decamped for the Lowcountry.

That less-than-perfect fit and Noel’s lingering contract situation made a move all the more logical. Now, Rensing has a blank slate, and he’ll also enjoy McKinze Gaines’ services into the 2026 season if he so chooses.

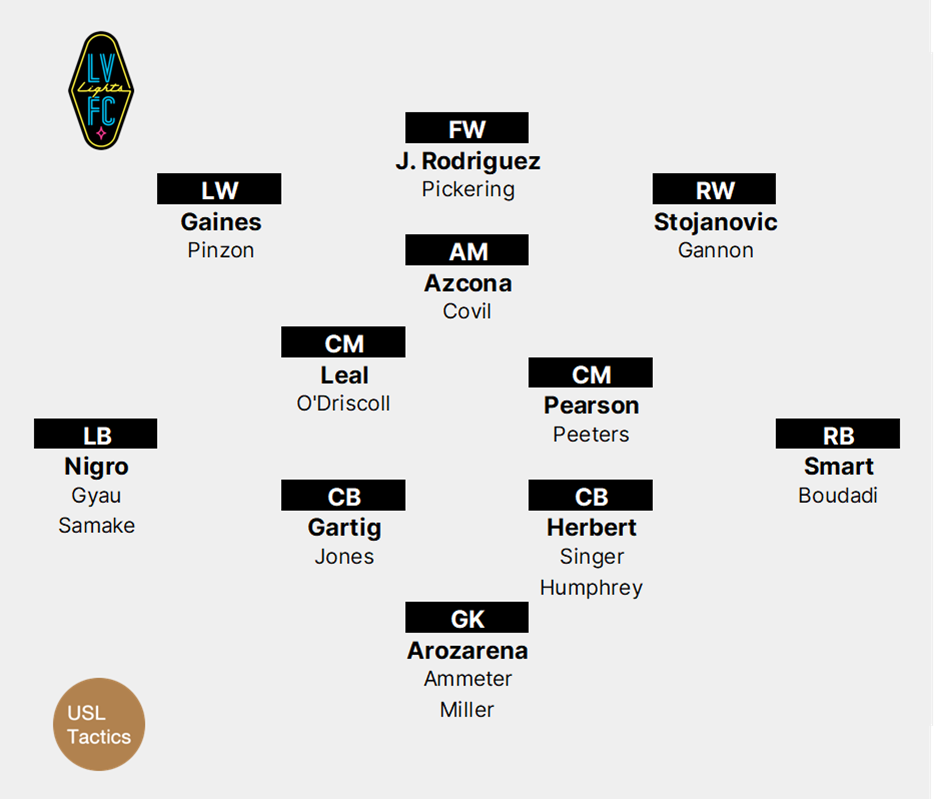

It’s easy to imagine what Las Vegas might look like in this new era. Dropping a defender, using Elias Gartig as the left-sided center back in a foursome – where he often played in 2024 – and getting Edison Azcona into the mix as the No. 10 in a jaunty 4-2-3-1 feels natural.

The rub? Azcona hasn’t made the squad for Las Vegas in months. His last competitive action came in the Gold Cup with the Dominican Republic, and even that was a brief cameo. In the interim, you can imagine Patrick Leal stepping up, but that leaves Las Vegas creatively bereft in the pivot. There aren’t obvious answers; more rebuilding steps are coming, and we aren’t privy to the whole picture as of yet.

On Coaching Trees

All of that hypothesizing assumes that Rensing won’t bring his own principles to the table. Every manager has their own ideas and preferences, after all. We (with “we” representing the American soccer community) like to lionize the idea of a coaching tree, but examples within the USL paint a more complex picture of what that lineage actually means.

Consider Luke Spencer in Tulsa. Spencer spent years with Louisville City as a player, coach, and academy luminary, but he cited culture rather than tactics as his main takeaway from that time in Kentucky in a recent conversation with Backheeled.

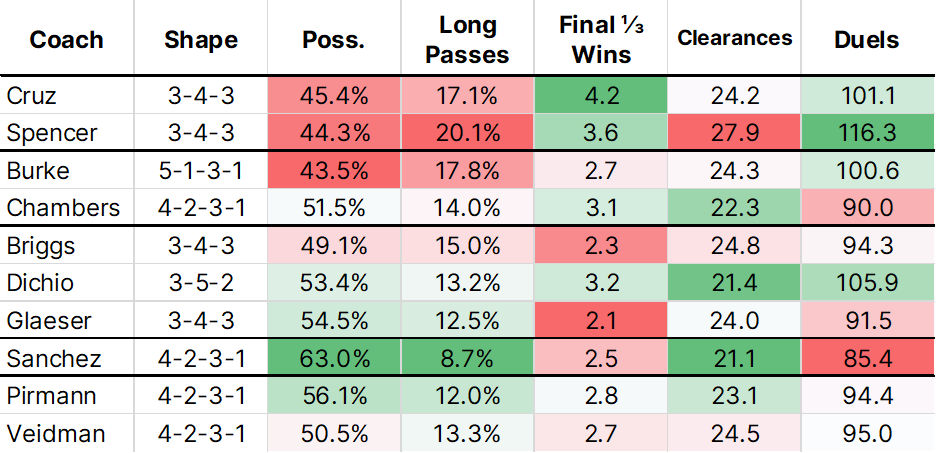

The numbers make Spencer’s Tulsa look quite similar to Danny Cruz’s Louisville, but they provide a mixed view of the coaching tree writ large. Cruz and Spencer have actually built remarkably similar teams if you look at the data, eschewing possession in favor of long passes and field-tilting high pressure.

By contrast, the Brendan Burke coaching tree that was forged in Bethlehem and Colorado Springs has yielded different results. Burke’s Hartford tends to be a low-block team that’s best on the counter, whereas his protege James Chambers plays a brighter 4-2-3-1 system and won a title thanks to a high-line setup.

Still, those differences aren’t necessarily ideological; they’re contextual. Burke is in a unique situation in Connecticut and brings highly idiosyncratic views of roster-building and squad rotation to the table. He’s dealing with a completely different setting than he did in the Rockies.

The Mark Briggs/Sacramento coaching tree has shown a similar penchant for individuality. Briggs was known for his defense-first back-three teams with the Republic, allowing for more expressiveness within his forward line. Ironically, he’s the one who’s gotten away from those principles to a certain extent, fostering a more expansive and vertical system in Birmingham. His former assistants in Matt Glaeser (Forward Madison) and Danny Dichio (Detroit City) have stuck to a familiar formula in the meantime.

Dennis Sanchez, who was the Academy Director in Sacramento during Briggs’ tenure but also spent a period with Charleston under Pirmann, sits between camps. His team is very good about achieving Republic-esque field tilt, but his system hews much closer to the Ben Pirmann brand of football.

If anything, it’s Pirmann whose coaching tree is the best-defined. Though figures like Sanchez and Spokane’s Leigh Veidman didn’t spend long stretches of time on his staff, they’ve adopted recognizably Battery-esque systems centered around possession-driven control. Veidman-ball is especially simpatico; the Velocity build in a pseudo-back three much of the time and prioritize rest defense structure to balance a complex attacking scheme.

What’s impossible to quantify is the environmental side of coaching lineage. Spencer noted that he “was heavily influenced…by [his] time at Louisville City…in terms of team chemistry, in terms of effort, in terms of consistency,” for a reason. Knowing how to manage a squad and define a culture is a far more atomic trait in comparison to game-by-game tactics.

In that case, the pre-eminence of the Pirmann coaching tree makes all the more sense. Clubs naturally look for winners; that’s the whole point of the sport. Of course you’re going to hire someone that’s been close to a serial winner like Ben Pirmann. The reason Pirmann has done all that winning isn’t just his preternatural tactical ability – he’s also a genuinely nice guy! The same compliment applies to Veidman, Sanchez, and Rensing.

Talk to a USL manager for long enough, and you’re almost guaranteed to hear the word “collective.” In a league where teams suffer from limited resources, strategic nous and raw talent can only take you so far. The clubs that fare best are defined by camaraderie and buy-in that starts with the head coach and permeates through the locker room.

That’s the promise of Devin Rensing. His college experience anticipates a willingness to work with young players. Rensing’s time spent with Pirmann hints at a stylish tactical identity and, more importantly, recommends his character. Talk to anyone that’s worked with the new Las Vegas manager, and you’ll understand that he’s an exceptional communicator.

Hiring a manager – much less one that can helm a genuine project and not just seek out short-term flash – is always difficult, but Rensing has the profile of a coach that’s built to succeed in an ever-changing USL. The Las Vegas Lights’ project is still in its early days, but hiring Devin Rensing is an astute choice in a complex, people-driven Championship.